|

|---|

| 5-HT1 | | 5-HT1A |

- Agonists: 8-OH-DPAT

- Adatanserin

- Amphetamine

- Antidepressants (e.g., etoperidone, hydroxynefazodone, nefazodone, trazodone, triazoledione, vilazodone, vortioxetine)

- Atypical antipsychotics (e.g., aripiprazole, asenapine, brexpiprazole, cariprazine, clozapine, lurasidone, quetiapine, ziprasidone)

- Azapirones (e.g., buspirone, eptapirone, gepirone, perospirone, tandospirone)

- Bay R 1531

- Befiradol

- BMY-14802

- Cannabidiol

- Dimemebfe

- Dopamine

- Ebalzotan

- Eltoprazine

- Enciprazine

- Ergolines (e.g., bromocriptine, cabergoline, dihydroergotamine, ergotamine, lisuride, LSD, methylergometrine (methylergonovine), methysergide, pergolide)

- F-11461

- F-12826

- F-13714

- F-14679

- F-15063

- F-15599

- Flesinoxan

- Flibanserin

- Flumexadol

- Hypidone

- Lesopitron

- LY-293284

- LY-301317

- mCPP

- MKC-242

- Naluzotan

- NBUMP

- Osemozotan

- Oxaflozane

- Pardoprunox

- Piclozotan

- Rauwolscine

- Repinotan

- Roxindole

- RU-24969

- S-14506

- S-14671

- S-15535

- Sarizotan

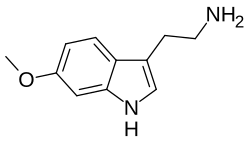

- Serotonin (5-HT)

- SSR-181507

- Sunepitron

- Tryptamines (e.g., 5-CT, 5-MeO-DMT, 5-MT, bufotenin, DMT, indorenate, N-Me-5-HT, psilocin, psilocybin)

- TGBA01AD

- U-92016-A

- Urapidil

- Vilazodone

- Xaliproden

- Yohimbine

|

- Positive allosteric modulators: Oleamide

|

- Antagonists: Atypical antipsychotics (e.g., iloperidone, risperidone, sertindole)

- AV965

- Beta blockers (e.g., alprenolol, carteolol, cyanopindolol, iodocyanopindolol, isamoltane, oxprenolol, penbutolol, pindobind, pindolol, propranolol, tertatolol)

- BMY-7378

- CSP-2503

- Dotarizine

- Ergolines (e.g., metergoline)

- FCE-24379

- Flopropione

- GR-46611

- Isamoltane

- Lecozotan

- Mefway

- Metitepine (methiothepin)

- MIN-117 (WF-516)

- MPPF

- NAN-190

- Robalzotan

- S-15535

- SB-649915

- SDZ 216-525

- Spiperone

- Spiramide

- Spiroxatrine

- UH-301

- WAY-100135

- WAY-100635

- Xylamidine

| |

|

|---|

| 5-HT1B |

- Agonists: Anpirtoline

- CGS-12066A

- CP-93129

- CP-94253

- CP-122288

- CP-135807

- Eltoprazine

- Ergolines (e.g., bromocriptine, dihydroergotamine, ergotamine, methylergometrine (methylergonovine), methysergide, pergolide)

- mCPP

- RU-24969

- Serotonin (5-HT)

- Triptans (e.g., avitriptan, donitriptan, eletriptan, sumatriptan, zolmitriptan)

- TFMPP

- Tryptamines (e.g., 5-BT, 5-CT, 5-MT, DMT)

- Vortioxetine

| | |

|

|---|

| 5-HT1D |

- Agonists: CP-122288

- CP-135807

- CP-286601

- Ergolines (e.g., bromocriptine, cabergoline, dihydroergotamine, ergotamine, LSD, methysergide)

- GR-46611

- L-694247

- L-772405

- mCPP

- PNU-109291

- PNU-142633

- Serotonin (5-HT)

- TGBA01AD

- Triptans (e.g., almotriptan, avitriptan, donitriptan, eletriptan, frovatriptan, naratriptan, rizatriptan, sumatriptan, zolmitriptan)

- Tryptamines (e.g., 5-BT, 5-CT, 5-Et-DMT, 5-MT, 5-(nonyloxy)tryptamine, DMT)

| | |

|

|---|

| 5-HT1E | |

|---|

| 5-HT1F | |

|---|

|

|---|

| 5-HT2 | | 5-HT2A |

- Agonists: 25H/NB series (e.g., 25I-NBF, 25I-NBMD, 25I-NBOH, 25I-NBOMe, 25B-NBOMe, 25C-NBOMe, 25TFM-NBOMe, 2CBCB-NBOMe, 25CN-NBOH, 2CBFly-NBOMe)

- 2Cs (e.g., 2C-B, 2C-E, 2C-I, 2C-T-2, 2C-T-7, 2C-T-21)

- 2C-B-FLY

- 2CB-Ind

- 5-Methoxytryptamines (5-MeO-DET, 5-MeO-DiPT, 5-MeO-DMT, 5-MeO-DPT, 5-MT)

- α-Alkyltryptamines (e.g., 5-Cl-αMT, 5-Fl-αMT, 5-MeO-αET, 5-MeO-αMT, α-Me-5-HT, αET, αMT)

- AL-34662

- AL-37350A

- Bromo-DragonFLY

- Dimemebfe

- DMBMPP

- DOx (e.g., DOB, DOC, DOI, DOM)

- Efavirenz

- Ergolines (e.g., 1P-LSD, ALD-52, bromocriptine, cabergoline, ergine (LSA), ergometrine (ergonovine), ergotamine, lisuride, LA-SS-Az, LSB, LSD, LSD-Pip, LSH, LSP, methylergometrine (methylergonovine), pergolide)

- Flumexadol

- IHCH-7113

- Jimscaline

- Lorcaserin

- MDxx (e.g., MDA (tenamfetamine), MDMA (midomafetamine), MDOH, MMDA)

- O-4310

- Oxaflozane

- PHA-57378

- PNU-22394

- PNU-181731

- RH-34

- SCHEMBL5334361

- Phenethylamines (e.g., lophophine, mescaline)

- Piperazines (e.g., BZP, quipazine, TFMPP)

- Serotonin (5-HT)

- TCB-2

- TFMFly

- Tryptamines (e.g., 5-BT, 5-CT, bufotenin, DET, DiPT, DMT, DPT, psilocin, psilocybin, tryptamine)

| |

- Antagonists: 5-I-R91150

- 5-MeO-NBpBrT

- AC-90179

- Adatanserin

- Altanserin

- Antihistamines (e.g., cyproheptadine, hydroxyzine, ketotifen, perlapine)

- AMDA

- Atypical antipsychotics (e.g., amperozide, aripiprazole, asenapine, blonanserin, brexpiprazole, carpipramine, clocapramine, clorotepine, clozapine, fluperlapine, gevotroline, iloperidone, lurasidone, melperone, mosapramine, ocaperidone, olanzapine, paliperidone, quetiapine, risperidone, sertindole, zicronapine, ziprasidone, zotepine)

- Chlorprothixene

- Cinanserin

- CSP-2503

- Deramciclane

- Dotarizine

- Eplivanserin

- Ergolines (e.g., amesergide, LY-53857, LY-215840, mesulergine, metergoline, methysergide, sergolexole)

- Fananserin

- Flibanserin

- Glemanserin

- Irindalone

- Ketanserin

- KML-010

- Landipirdine

- LY-393558

- mCPP

- Medifoxamine

- Metitepine (methiothepin)

- MIN-117 (WF-516)

- Naftidrofuryl

- Nantenine

- Nelotanserin

- Opiranserin (VVZ-149)

- Pelanserin

- Phenoxybenzamine

- Pimavanserin

- Pirenperone

- Pizotifen

- Pruvanserin

- Rauwolscine

- Ritanserin

- Roluperidone

- S-14671

- Sarpogrelate

- Serotonin antagonists and reuptake inhibitors (e.g., etoperidone, hydroxynefazodone, lubazodone, mepiprazole, nefazodone, triazoledione, trazodone)

- SR-46349B

- TGBA01AD

- Teniloxazine

- Temanogrel

- Tetracyclic antidepressants (e.g., amoxapine, aptazapine, esmirtazapine, maprotiline, mianserin, mirtazapine)

- Tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline)

- Typical antipsychotics (e.g., chlorpromazine, fluphenazine, haloperidol, loxapine, perphenazine, pimozide, pipamperone, prochlorperazine, setoperone, spiperone, spiramide, thioridazine, thiothixene, trifluoperazine)

- Volinanserin

- Xylamidine

- Yohimbine

| |

|

|---|

| 5-HT2B |

- Agonists: 4-Methylaminorex

- Aminorex

- Amphetamines (e.g., chlorphentermine, cloforex, dexfenfluramine, fenfluramine, levofenfluramine, norfenfluramine)

- BW-723C86

- DOx (e.g., DOB, DOC, DOI, DOM)

- Ergolines (e.g., cabergoline, dihydroergocryptine, dihydroergotamine, ergotamine, methylergometrine (methylergonovine), methysergide, pergolide)

- Lorcaserin

- MDxx (e.g., MDA (tenamfetamine), MDMA (midomafetamine), MDOH, MMDA)

- Piperazines (e.g., TFMPP)

- PNU-22394

- Ro60-0175

- Serotonin (5-HT)

- Tryptamines (e.g., 5-BT, 5-CT, 5-MT, α-Me-5-HT, bufotenin, DET, DiPT, DMT, DPT, psilocin, psilocybin, tryptamine)

|

- Antagonists: Agomelatine

- Atypical antipsychotics (e.g., amisulpride, aripiprazole, asenapine, brexpiprazole, cariprazine, clozapine, N-desalkylquetiapine (norquetiapine), N-desmethylclozapine (norclozapine), olanzapine, pipamperone, quetiapine, risperidone, ziprasidone)

- Cyproheptadine

- EGIS-7625

- Ergolines (e.g., amesergide, bromocriptine, lisuride, LY-53857, LY-272015, mesulergine)

- Ketanserin

- LY-393558

- mCPP

- Metadoxine

- Metitepine (methiothepin)

- Pirenperone

- Pizotifen

- Propranolol

- PRX-08066

- Rauwolscine

- Ritanserin

- RS-127445

- Sarpogrelate

- SB-200646

- SB-204741

- SB-206553

- SB-215505

- SB-221284

- SB-228357

- SDZ SER-082

- Tegaserod

- Tetracyclic antidepressants (e.g., amoxapine, mianserin, mirtazapine)

- Trazodone

- Typical antipsychotics (e.g., chlorpromazine)

- TIK-301

- Yohimbine

| |

|

|---|

| 5-HT2C |

- Agonists: 2Cs (e.g., 2C-B, 2C-E, 2C-I, 2C-T-2, 2C-T-7, 2C-T-21)

- 5-Methoxytryptamines (5-MeO-DET, 5-MeO-DiPT, 5-MeO-DMT, 5-MeO-DPT, 5-MT)

- α-Alkyltryptamines (e.g., 5-Cl-αMT, 5-Fl-αMT, 5-MeO-αET, 5-MeO-αMT, α-Me-5-HT, αET, αMT)

- A-372159

- AL-38022A

- Alstonine

- CP-809101

- Dimemebfe

- DOx (e.g., DOB, DOC, DOI, DOM)

- Ergolines (e.g., ALD-52, cabergoline, dihydroergotamine, ergine (LSA), ergotamine, lisuride, LA-SS-Az, LSB, LSD, LSD-Pip, LSH, LSP, pergolide)

- Flumexadol

- Lorcaserin

- MDxx (e.g., MDA (tenamfetamine), MDMA (midomafetamine), MDOH, MMDA)

- MK-212

- ORG-12962

- ORG-37684

- Oxaflozane

- PHA-57378

- Phenethylamines (e.g., lophophine, mescaline)

- Piperazines (e.g., aripiprazole, BZP, mCPP, quipazine, TFMPP)

- PNU-22394

- PNU-181731

- Ro60-0175

- Ro60-0213

- Serotonin (5-HT)

- Tryptamines (e.g., 5-BT, 5-CT, bufotenin, DET, DiPT, DMT, DPT, psilocin, psilocybin, tryptamine)

- Vabicaserin

- WAY-629

- WAY-161503

- YM-348

| |

- Antagonists: Adatanserin

- Agomelatine

- Atypical antipsychotics (e.g., asenapine, clorotepine, clozapine, fluperlapine, iloperidone, melperone, olanzapine, paliperidone, quetiapine, risperidone, sertindole, ziprasidone, zotepine)

- Captodiame

- CEPC

- Cinanserin

- Cyproheptadine

- Deramciclane

- Desmetramadol

- Dotarizine

- Eltoprazine

- Ergolines (e.g., amesergide, bromocriptine, LY-53857, LY-215840, mesulergine, metergoline, methysergide, sergolexole)

- Etoperidone

- Fluoxetine

- FR-260010

- Irindalone

- Ketanserin

- Ketotifen

- Latrepirdine (dimebolin)

- Medifoxamine

- Metitepine (methiothepin)

- Nefazodone

- Pirenperone

- Pizotifen

- Propranolol

- Ritanserin

- RS-102221

- S-14671

- SB-200646

- SB-206553

- SB-221284

- SB-228357

- SB-242084

- SB-243213

- SDZ SER-082

- Tedatioxetine

- Tetracyclic antidepressants (e.g., amoxapine, aptazapine, esmirtazapine, maprotiline, mianserin, mirtazapine)

- TIK-301

- Tramadol

- Trazodone

- Tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline, nortriptyline)

- Typical antipsychotics (e.g., chlorpromazine, loxapine, pimozide, pipamperone, thioridazine)

- Xylamidine

| |

|

|---|

|

|---|

| 5-HT3–7 | | 5-HT3 |

- Agonists: Alcohols (e.g., butanol, ethanol (alcohol), trichloroethanol)

- m-CPBG

- Phenylbiguanide

- Piperazines (e.g., BZP, mCPP, quipazine)

- RS-56812

- Serotonin (5-HT)

- SR-57227

- SR-57227A

- Tryptamines (e.g., 2-Me-5-HT, 5-CT, bufotenidine (5-HTQ))

- Volatiles/gases (e.g., halothane, isoflurane, toluene, trichloroethane)

- YM-31636

| |

- Antagonists: Alosetron

- Anpirtoline

- Arazasetron

- AS-8112

- Atypical antipsychotics (e.g., clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine)

- Azasetron

- Batanopride

- Bemesetron (MDL-72222)

- Cilansetron

- CSP-2503

- Dazopride

- Dolasetron

- Galanolactone

- Granisetron

- Lerisetron

- Memantine

- Ondansetron

- Palonosetron

- Ramosetron

- Renzapride

- Ricasetron

- Tedatioxetine

- Tetracyclic antidepressants (e.g., amoxapine, mianserin, mirtazapine)

- Thujone

- Tropanserin

- Tropisetron

- Typical antipsychotics (e.g., loxapine)

- Volatiles/gases (e.g., nitrous oxide, sevoflurane, xenon)

- Vortioxetine

- Zacopride

- Zatosetron

| |

- Unknown/unsorted: LY-53857

- Piperazines (e.g., naphthylpiperazine)

|

|

|---|

| 5-HT4 | |

|---|

| 5-HT5A | |

|---|

| 5-HT6 |

- Agonists: Ergolines (e.g., dihydroergocryptine, dihydroergotamine, ergotamine, lisuride, LSD, mesulergine, metergoline, methysergide)

- Hypidone

- Serotonin (5-HT)

- Tryptamines (e.g., 2-Me-5-HT, 5-BT, 5-CT, 5-MT, Bufotenin, E-6801, E-6837, EMD-386088, EMDT, LY-586713, N-Me-5-HT, ST-1936, tryptamine)

- WAY-181187

- WAY-208466

|

- Antagonists: ABT-354

- Atypical antipsychotics (e.g., aripiprazole, asenapine, clorotepine, clozapine, fluperlapine, iloperidone, olanzapine, tiospirone)

- AVN-101

- AVN-211

- AVN-322

- AVN-397

- BGC20-760

- BVT-5182

- BVT-74316

- Cerlapirdine

- EGIS-12233

- GW-742457

- Idalopirdine

- Ketanserin

- Landipirdine

- Latrepirdine (dimebolin)

- Masupirdine

- Metitepine (methiothepin)

- MS-245

- PRX-07034

- Ritanserin

- Ro 04-6790

- Ro 63-0563

- SB-258585

- SB-271046

- SB-357134

- SB-399885

- SB-742457

- Tetracyclic antidepressants (e.g., amoxapine, mianserin)

- Tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline, clomipramine, doxepin, nortriptyline)

- Typical antipsychotics (e.g., chlorpromazine, loxapine)

| |

|

|---|

| 5-HT7 | |

- Antagonists: Atypical antipsychotics (e.g., amisulpride, aripiprazole, asenapine, brexpiprazole, clorotepine, clozapine, fluperlapine, olanzapine, risperidone, sertindole, tiospirone, ziprasidone, zotepine)

- Butaclamol

- DR-4485

- EGIS-12233

- Ergolines (e.g., 2-Br-LSD (BOL-148), amesergide, bromocriptine, cabergoline, dihydroergotamine, ergotamine, LY-53857, LY-215840, mesulergine, metergoline, methysergide, sergolexole)

- JNJ-18038683

- Ketanserin

- LY-215840

- Metitepine (methiothepin)

- Ritanserin

- SB-258719

- SB-258741

- SB-269970

- SB-656104

- SB-656104A

- SB-691673

- SLV-313

- SLV-314

- Spiperone

- SSR-181507

- Tetracyclic antidepressants (e.g., amoxapine, maprotiline, mianserin, mirtazapine)

- Tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline, clomipramine, imipramine)

- Typical antipsychotics (e.g., acetophenazine, chlorpromazine, chlorprothixene, fluphenazine, loxapine, pimozide)

- Vortioxetine

|

- Negative allosteric modulators: Oleamide

| |

|

|---|

|

|---|

- See also: Receptor/signaling modulators

- Adrenergics

- Dopaminergics

- Melatonergics

- Monoamine reuptake inhibitors and releasing agents

- Monoamine metabolism modulators

- Monoamine neurotoxins

|