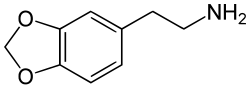

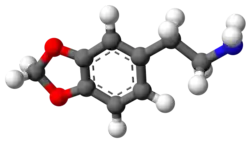

3,4-Methylenedioxyphenethylamine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | 3,4-Methylenedioxyphenethylamine; Methyleneddioxyphenethylamine; 3,4-MDPEA; Homopiperonylamine; EA-1297 |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.014.601 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C9H11NO2 |

| Molar mass | 165.192 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

MDPEA, also known as 3,4-methylenedioxyphenethylamine or as homopiperonylamine, is a possible psychoactive drug of the phenethylamine and methylenedioxyphenethylamine families.[2] It is the 3,4-methylenedioxy derivative of phenethylamine (PEA).[2] The drug is structurally related to 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA), but lacks the methyl group at the α carbon.[2] It is a key parent compound of a large group of compounds known as entactogens such as MDMA ("ecstasy").[2]

Use and effects

According to Alexander Shulgin in his book PiHKAL (Phenethylamines I Have Known and Loved), MDPEA was inactive at doses of up to 300 mg orally.[2] This is likely because of extensive first-pass metabolism by the enzyme monoamine oxidase (MAO).[2] However, if MDPEA were either used in high enough of doses (e.g., 1–2 grams), or in combination with a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI), it is probable that it would become active, though it would likely have a relatively short duration. This idea is similar in concept to the use of monoamine oxidase A (MAO-A) inhibitors to augment dimethyltryptamine (DMT) as in ayahuasca[3] and of monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) inhibitors to potentiate phenethylamine (PEA).[4][5]

Besides being evaluated by Shulgin, MDPEA was studied at Edgewood Arsenal in the 1950s and was administered to humans at doses of up to 5.0 mg/kg (350 mg for a 70-kg person) by intravenous injection, although the results of these tests do not seem to have been released.[6]

Interactions

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

MDPEA produces sympathomimetic effects when administered intravenously at sufficiently high doses in dogs.[7][8] It was about half as potent in this regard as PEA.[7][8] The effects and toxicity of MDPEA in various animal species via intravenous injection have been studied and described.[6]

Chemistry

Properties

Analogues

Analogues of MDPEA include 3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methylphenethylamine (MDMPEA), lophophine (5-methoxy-MDPEA), mescaline (3,4,5-trimethoxyphenethylamine), 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA), and 3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methylamphetamine (MDMA), among others.[2]

History

MDPEA was first described in the scientific literature by Gordon Alles by 1959.[7][8] It was studied at Edgewood Arsenal under the code name EA-1297 in the 1950s, being administered by humans in 1952.[2][6] The drug was described by Alexander Shulgin in his 1991 book PiHKAL (Phenethylamines I Have Known and Loved).[2]

Society and culture

Legal status

Poland

MDPEA is a controlled substance in Poland.[1]

See also

References

- 1 2 "Ustawa z dnia 15 kwietnia 2011 r. o zmianie ustawy o przeciwdziałaniu narkomanii ( Dz.U. 2011 nr 105 poz. 614 )". Internetowy System Aktów Prawnych. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Shulgin A, Shulgin A (September 1991). PiHKAL: A Chemical Love Story. Berkeley, California: Transform Press. ISBN 0-9630096-0-5. OCLC 25627628. https://www.erowid.org/library/books_online/pihkal/pihkal115.shtml

- ↑ Egger K, Aicher HD, Cumming P, Scheidegger M (September 2024). "Neurobiological research on N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT) and its potentiation by monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibition: from ayahuasca to synthetic combinations of DMT and MAO inhibitors". Cell Mol Life Sci. 81 (1): 395. doi:10.1007/s00018-024-05353-6. PMC 11387584. PMID 39254764.

- ↑ McKean AJ, Leung JG, Dare FY, Sola CL, Schak KM (2015). "The Perils of Illegitimate Online Pharmacies: Substance-Induced Panic Attacks and Mood Instability Associated With Selegiline and Phenylethylamine". Psychosomatics. 56 (5): 583–587. doi:10.1016/j.psym.2015.05.003. PMID 26198572.

- ↑ Monteith S, Glenn T, Bauer R, Conell J, Bauer M (March 2016). "Availability of prescription drugs for bipolar disorder at online pharmacies". J Affect Disord. 193: 59–65. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.043. PMID 26766033.

- 1 2 3 Passie T, Benzenhöfer U (January 2018). "MDA, MDMA, and other "mescaline-like" substances in the US military's search for a truth drug (1940s to 1960s)". Drug Test Anal. 10 (1): 72–80. doi:10.1002/dta.2292. PMID 28851034.

- 1 2 3 Alles GA (1959). "Some Relations Between Chemical Structure and Physiological Action of Mescaline and Related Compounds / Structure and Action of Phenethylamines". In Abramson HA (ed.). Neuropharmacology: Transactions of the Fourth Conference, September 25, 26, and 27, 1957, Princeton, N. J. New York: Josiah Macy Foundation. pp. 181–268. OCLC 9802642.

We studied the two compounds in Figure 38 and found that after intravenous injection into dogs, these compounds were about one-half or one-third as active in their peripheral activities as the unsubstituted compounds. [...] FIGURE 38. [...] 3,4-Methylenedioxyphenethylamine. Homopiperonylamine. [...] 3,4-Methylenedioxyphenisopropylamine. Methylenedioxy-amphetamine (MDA).

- 1 2 3 Alles GA (1959). "Subjective Reactions to Phenethylamine Hallucinogens". A Pharmacologic Approach to the Study of the Mind. Springfield: CC Thomas. pp. 238–250 (241–246). ISBN 978-0-398-04254-7.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ↑ "1,3-Benzodioxole-5-ethanamine". PubChem. Retrieved 22 October 2025.