Ehrlichiosis

| Ehrlichiosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Human ehrlichiosis;[1] human monocytic ehrlichiosis (HME) | |

| |

| The lone star tick, which is one of three ticks that can spread Ehrlichiosis. It is characterized by the white dot on its back.[2] | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Fever, headache, tiredness[3] |

| Complications | Meningitis, respiratory failure, kidney failure, liver failure[3] |

| Usual onset | 5 to 14 days after exposure[3] |

| Causes | Ehrlichia, Anaplasma[4][5] |

| Diagnostic method | PCR, serology testing[6] |

| Differential diagnosis | Rocky Mountain spotted fever, mononucleosis, dengue, malaria, lupus, Kawasaki disease[5] |

| Prevention | Avoiding ticks[5] |

| Treatment | Doxycycline[7] |

| Prognosis | 1% risk of death[8] |

| Frequency | 3.2 per million year (USA)[5] |

Ehrlichiosis is a tick-borne infection caused by bacteria of the Ehrlichia type.[4] Common symptoms include fever, headache, and tiredness.[3] While a rash occurs in over half of children, it is present in less than a third of adults.[3] Onset is generally 5 to 14 days after exposure.[3] Complications may include meningitis, respiratory failure, kidney failure, or liver failure.[3]

The disease is mostly spread by two types of ticks: lone star and blacklegged ticks.[4] Though, may rarely occur from a blood transfusion.[4] Risks for severe disease include a poor immune system and older age.[5] Diagnosis may be supported by PCR or serology testing.[6]

Treatment for people of all ages is typically with doxycycline.[7] This should be given when the diagnosis is suspected, but is not recommended to simply prevent the disease following a tick bite.[7] With treatment most people improve within 48 hours and resistance has not been documented.[7] With one type, E. chaffeensis, hospitalization was required in half of cases.[5] About 1% of people affected die.[8]

Ehrlichiosis affects about than 3.2 per million people a year in the USA (about 2,000 cases).[5][8] It is the second most common tick-borne infection after lyme.[5] It occurs mostly during summer in the midwest and Eastern United States.[4] Males are more commonly affected than females.[8] The disease was first identified in 1986.[5] It has becoming more common as a result of climate change.[5]

Signs and symptoms

Specific symptoms include fever, chills, severe headaches, muscle aches, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, loss of appetite, confusion, and a splotchy or pinpoint rash.[9] Ehrlichiosis can also blunt the immune system by suppressing production of TNF-alpha, which may lead to opportunistic infections[10].

About 3% of human monocytic ehrlichiosis cases result in death; however, these deaths occur "most commonly in immunosuppressed individuals who develop respiratory distress syndrome, hepatitis, or opportunistic nosocomial infections."[11]

Complications

In terms of the complications associated with Ehrlichiosis we find that immunocompromised individuals are most at risk:[5]

- Bleeding

- Respiratory failure

- Kidney failure

- Neurological issue

- Septic shock

Cause

.png)

Six species cause human infection:[12][13]

- Anaplasma phagocytophilum causes human granulocytic anaplasmosis. It occurs regularly in New England and the north-central and Pacific regions of the United States.

- Ehrlichia ewingii (causes human ewingii ehrlichiosis. E. ewingii primarily infects deer and dogs).[14])

- Ehrlichia chaffeensis ( causes human monocytic ehrlichiosis. E. chaffeensis is most common in the south-central and southeastern states.[15] [16])

- Ehrlichia canis

- Neorickettsia sennetsu

- Ehrlichia muris eauclairensis

In 2008, human infection by a Panola Mountain (in Georgia, USA) Ehrlichia species was reported.[17] On August 3, 2011, infection by a yet-unnamed bacterium in the genus Ehrlichia was reported, carried by deer ticks and causing flu-like symptoms in at least 25 people in Minnesota and Wisconsin. Until then, human ehrlichiosis was thought to be very rare or absent in both states.[18] The new species, which is genetically very similar to an Ehrlichia species found in Eastern Europe and Japan called E. muris, was identified at a Mayo Clinic Health System hospital in Eau Claire.[18]

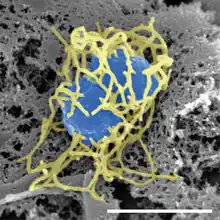

Ehrlichia species are transported between cells through the host-cell filopodia during the initial stages of infection; whereas, in the final stages of infection, the pathogen ruptures the host cell membrane.[19]

Spread

In terms of transmission Ehrlichiosis is primarily transmitted through the bite of an infected tick. The most common carriers are the lone star tick Amblyomma americanum and the blacklegged tick Ixodes scapularis. These ticks become infected after feeding on animals like deer, dogs, or coyotes that carry the bacteria.[20][5]

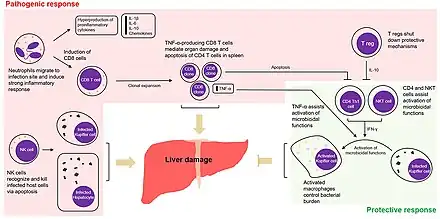

Mechanism

Most of the presentation of ehrlichiosis can likely be ascribed to the immune dysregulation that it causes. A "toxic shock-like" syndrome is seen in some severe cases of ehrlichiosis. Some cases can present with purpura and in one such case, the organisms were present in such overwhelming numbers that in 1991, Dr. Aileen Marty of the AFIP was able to demonstrate the bacteria in human tissues using standard stains, and later proved that the organisms were indeed Ehrlichia using immunoperoxidase stains.[22] Experiments in models further support this hypothesis, as mice lacking TNF-alpha I/II receptors are resistant to liver injury caused by Ehrlichia infection.[23] It is an obligate intracellular bacteria that infect and kill white blood cells.[24]

Diagnosis

In terms of the diagnosis of Ehrlichiosis we find that a blood test is done to ascertain if the individual is infected with this illness[25]

Differential diagnosis

The DDx finds the following, for an individual suspected of having Ehrlichiosis:[26]

- Endocarditis

- Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis

- Hepatitis

- Leptospirosis

- Q fever

- Toxic shock syndrome

- Tick-borne diseases

- Neisseria meningitidis

- Cytomegalovirus infection

- Dengue fever

Prevention

No human vaccine is available. Tick control is the main measure against the disease. In late 2012, a vaccine for canine monocytic ehrlichiosis was announced.[5]

Measures of tick bite prevention include staying out of tall grassy areas that ticks tend to live in, treating clothes and gear that a tick could jump on, using EPA approved bug repellent, tick checks for all humans, animals, and gear that potentially came into contact with a tick, and showering soon after being in an area that ticks might also be in.[27]

Treatment

Doxycycline and minocycline are the medications of choice. For people allergic to antibiotics of the tetracycline class, rifampin is an alternative.[14] Early clinical experience suggested that chloramphenicol may also be effective, but in vitro susceptibility testing revealed resistance.[28]

Epidemiology

Ehrlichiosis is a nationally notifiable disease in the United States. Cases have been reported in every month of the year, but most cases are reported during April–September.[29][30][31] These months are also the peak months for tick activity in the United States.[13] The majority of cases of Ehrlichiosis tend to be in the United States. The states affected most include "the southeastern and south-central United States, from the East Coast extending westward to Texas."[13]

Since the first case of Ehrlichiosis was reported in 2000, cases reported to the CDC have increased, for example, in 2000, 200 cases were reported and in 2019, 2,093 cases were reported. Fortunately, the "proportion of ehrlichiosis patients that died as a result of infection" has gone down since 2000.[13]

From 2008 to 2012, the average yearly incidence of ehrlichiosis was 3.2 cases per million persons. This is more than twice the estimated incidence for 2000–2007.[31] The incidence rate increases with age, with the ages of 60–69 years being the highest age-specific years. Children less than 10 years and adults aged 70 years and older have the highest case-fatality rates.[31] A documented higher risk of death exists among persons who are immunosuppressed.[29]

Cases of E. chaffeensis have not been reported in Canada as of 2022; though, Analplasma has.[32]

.jpg)

History

Ehrlichiosis was first observed by German microbiologist Paul Ehrlich in the 19th century. He was credited with discovering the microbiological agent responsible for Ehrlichiosis, which was later named Ehrlichia.[34]

Other animals

Dogs infected with Ehrlichia often show lameness, lethargy, enlarged lymph nodes, and loss of appetite during the acute phase, which is one to three weeks after infection. Other symptoms include cough, diarrhea, vomiting, abnormal bruising and/or bleeding, fever, and loss of balance.[35]

See also

References

- ↑ "Ehrlichiosis (Concept Id: C0085399) - MedGen - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2 January 2025.

- ↑ CDC (2019-01-17). "Ehrlichiosis home | CDC". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 2021-11-01. Retrieved 2021-11-03.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 "Clinical Signs and Symptoms of Ehrlichiosis". Ehrlichiosis. 20 May 2024. Archived from the original on 18 December 2024. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 "Clinical Overview of Ehrlichiosis". Ehrlichiosis. 20 May 2024. Archived from the original on 16 December 2024. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 Snowden, Jessica; Simonsen, Kari A. (2025). "Ehrlichiosis". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 28722995. Archived from the original on 2024-11-20. Retrieved 2025-01-09.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Clinical Testing and Diagnosis for Ehrlichiosis". Ehrlichiosis. 20 May 2024. Archived from the original on 13 December 2024. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 "Clinical Care of Ehrlichiosis". Ehrlichiosis. 20 May 2024. Archived from the original on 13 December 2024. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 "Ehrlichiosis Epidemiology and Statistics". Ehrlichiosis. 30 May 2024. Archived from the original on 26 January 2025. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

- ↑ Baker, Meghan; Yokoe, Deborah S.; Stelling, John; Kaganov, Rebecca E.; Letourneau, Alyssa R.; O'Brien, Thomas; Kulldorff, Martin; Babalola, Damilola; Barrett, Craig; Drees, Marci; Platt, Richard (2015). "Automated Outbreak Detection of Hospital-Associated Infections". Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 2 (suppl_1). doi:10.1093/ofid/ofv131.60. ISSN 2328-8957.

- ↑ Ismail, Nahed; Sharma, Aditya; Soong, Lynn; Walker, David H. (2022). "Protective Immunity and Immunopathology in Ehrlichiosis". Zoonoses. 2 (1): 10.15212/zoonoses–2022–0009. doi:10.15212/zoonoses-2022-0009. PMC 9300479. PMID 35876763.

- ↑ Thomas, Rachael J; Dumler, J Stephen; Carlyon, Jason A (1 August 2009). "Current management of human granulocytic anaplasmosis, human monocytic ehrlichiosis and ehrlichiosis". Expert Review of Anti-infective Therapy. 7 (6): 709–722. doi:10.1586/eri.09.44. PMC 2739015. PMID 19681699.

- ↑ Dumler JS, Madigan JE, Pusterla N, Bakken JS (July 2007). "Ehrlichioses in humans: epidemiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment". Clin. Infect. Dis. 45 (Suppl 1): S45–51. doi:10.1086/518146. PMID 17582569.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 CDC (2021-08-04). "Ehrlichiosis epidemiology and statistics | CDC". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 2021-03-19. Retrieved 2021-11-03.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Goddard J (September 1, 2008). "What Is New With Ehrlichiosis?". Infections in Medicine.

- ↑ "Human Monocytic Ehrlichiosis (HME) - Symptoms, Causes, Treatment | NORD". rarediseases.org. Archived from the original on 5 January 2025. Retrieved 8 January 2025.

- ↑ Paddock, Christopher D.; Childs, James E. (January 2003). "Ehrlichia chaffeensis: a Prototypical Emerging Pathogen". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 16 (1): 37–64. doi:10.1128/CMR.16.1.37-64.2003. PMC 145301. PMID 12525424.

- ↑ Reeves WK, Loftis AD, Nicholson WL, Czarkowski AG (2008). "The first report of human illness associated with the Panola Mountain Ehrlichia species: a case report". Journal of Medical Case Reports. 2: 139. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-2-139. PMC 2396651. PMID 18447934.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Steenhuysen, J. (3 August 2011). "New tick-borne bacterium found in upper Midwest". Reuters. Archived from the original on 2012-06-09.

- ↑ Thomas S, Popov VL, Walker DH (2010). Kaushal D (ed.). "Exit Mechanisms of the Intracellular Bacterium Ehrlichia". PLOS ONE. 5 (12): e15775. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...515775T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0015775. PMC 3004962. PMID 21187937.

- ↑ "Transmission of the bacteria which cause ehrlichiosis | CDC". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 17 January 2019. Archived from the original on 29 November 2022. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

- ↑ Tominello, Tyler R.; Oliveira, Edson R. A.; Hussain, Shah S.; Elfert, Amr; Wells, Jakob; Golden, Brandon; Ismail, Nahed (2019). "Emerging Roles of Autophagy and Inflammasome in Ehrlichiosis". Frontiers in Immunology. 10: 1011. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.01011. ISSN 1664-3224. PMC 6517498. PMID 31134081.

- ↑ Marty AM, Dumler JS, Imes G, Brusman HP, Smrkovski LL, Frisman DM (August 1995). "Ehrlichiosis mimicking thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Case report and pathological correlation". Hum. Pathol. 26 (8): 920–5. doi:10.1016/0046-8177(95)90017-9. PMID 7635455.

- ↑ McBride JW, Walker DH (2011). "Molecular and cellular pathobiology of Ehrlichia infection: targets for new therapeutics and immunomodulation strategies". Expert Rev Mol Med. 13: e3. doi:10.1017/S1462399410001730. PMC 3767467. PMID 21276277.

- ↑ Dawson, Jacqueline E.; Marty, Aileen M. (1997). "Ehrlichiosis". In Horsburgh, C.R.; Nelson, A.M. (eds.). Pathology of emerging Infections. Vol. 1. American Society for Microbiology Press. ISBN 1555811205.

- ↑ "Diagnosis and testing of ehrlichiosis | CDC". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 17 January 2019. Archived from the original on 30 September 2022. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

- ↑ Snowden, Jessica; Simonsen, Kari A. (2024). "Ehrlichiosis". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 28722995. Archived from the original on 2024-11-20. Retrieved 2025-01-09.

- ↑ CDC (2020-07-01). "Preventing tick bites on people | CDC". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 2021-07-29. Retrieved 2021-12-02.

- ↑ Thomas, Rachael J; Dumler, J Stephen; Carlyon, Jason A (August 2009). "Current management of human granulocytic anaplasmosis, human monocytic ehrlichiosis and Ehrlichia ewingii ehrlichiosis". Expert Review of Anti-infective Therapy. 7 (6): 709–722. doi:10.1586/eri.09.44. PMC 2739015. PMID 19681699.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Dahlgren FS, Heitman KN, Drexler NA, Massung RF, Behravesh CB. "Human granulocytic anaplasmosis in the United States from 2008 to 2012: a summary of national surveillance data". Am J Trop Med Hyg 2015;93:66–72. Archived 2021-11-12 at archive.today

- ↑ Drexler, Naomi A.; Dahlgren, F. Scott; Heitman, Kristen Nichols; Massung, Robert F.; Paddock, Christopher D.; Behravesh, Casey Barton (2016-01-06). "National Surveillance of Spotted Fever Group Rickettsioses in the United States, 2008-2012". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 94 (1): 26–34. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.15-0472. ISSN 1476-1645. PMC 4710440. PMID 26324732.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Nichols Heitman, Kristen; Dahlgren, F. Scott; Drexler, Naomi A.; Massung, Robert F.; Behravesh, Casey Barton (2016-01-06). "Increasing Incidence of Ehrlichiosis in the United States: A Summary of National Surveillance of Ehrlichia chaffeensis and Ehrlichia ewingii Infections in the United States, 2008-2012". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 94 (1): 52–60. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.15-0540. ISSN 1476-1645. PMC 4710445. PMID 26621561.

- ↑ "A review of ticks in Canada and health risks from exposure | National Collaborating Centre for Environmental Health | NCCEH - CCSNE". ncceh.ca. Archived from the original on 2024-12-13. Retrieved 2025-01-27.

- ↑ "Ehrlichiosis Epidemiology and Statistics". Ehrlichiosis. 30 May 2024.

- ↑ Walker, David H.; Dumler, J. Stephen (1996). "Emergence of the Ehrlichioses as Human Health Problems - Volume 2, Number 1—January 1996 - Emerging Infectious Diseases journal - CDC". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2 (1): 18–29. doi:10.3201/eid0201.960102. PMC 2639805. PMID 8903194. Archived from the original on 2024-12-20. Retrieved 2025-01-09.

- ↑ "Ehrlichiosis in Dogs". Pet MD. Archived from the original on 24 January 2023. Retrieved 24 January 2023.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |