Brazilian purpuric fever

| Brazilian purpuric fever | |

|---|---|

| Other names: BPF clone conjunctivitis[1][2] | |

| |

| |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | High fever, vomiting, abdominal pain, and purpura[4][5] |

| Causes | Haemophilus influenzae biogroup aegyptius[6] |

| Diagnostic method | Blood culture[7] |

| Differential diagnosis | Meningococcemia[8] |

| Treatment | Antibiotics(ampicillin)[4] |

Brazilian purpuric fever (BPF) is an illness of children caused by the bacterium Haemophilus influenzae biogroup aegyptius which is ultimately fatal due to sepsis. BPF was first recognized in the São Paulo state of Brazil in 1984. At this time, young children between the ages of 3 months and 10 years were contracting a strange illness which was characterized by high fever and purpuric lesions on the body. These cases were all fatal, and originally thought to be due to meningitis. It was not until the autopsies were conducted that the cause of these deaths was confirmed to be infection by H. influenzae aegyptius. Although BPF was thought to be confined to Brazil, other cases occurred in Australia and the United States.[7][9][10]

Signs and symptoms

In documented BPF cases, the symptoms include high fever , nausea, vomiting, severe abdominal pain, septic shock, and ultimately death. A history of conjunctivitis 30 days prior to the onset of fever was also present in the documented BPF cases.[4][5][8]

The physical presentation of children infected with BPF include purpuric skin lesions affecting mainly the face and extremities, cyanosis, rapid necrosis of soft tissue, particularly the hands, feet, nose, and ears. Analysis of the fatalities due to BPF showed hemorrhage in the skin, lungs, and adrenal glands.[4][5][8]

Cause

Haemophilus influenzae biogroup aegyptius (Hae) is a Gram-negative bacterium known for causing both mild and severe illnesses, particularly in children.[6][11]

Transmission

The eye gnat (Liohippelates) was thought to be the cause of the conjunctivitis epidemic which occurred in Mato Grosso do Sul in 1991. These gnats were extracted from the conjunctival secretions of the children who were infected with conjunctivitis. 19 of those children developed BPF following the conjunctivitis. Other modes of transmission include contact with the conjunctival discharges of infected people.[12][2]

Pathogenesis

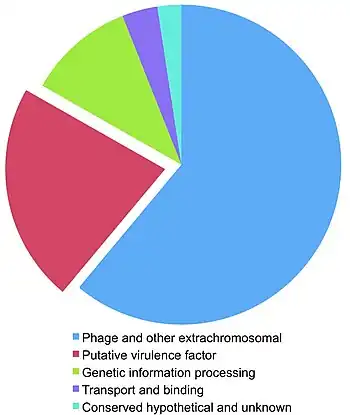

The pathogenesis of BPF is not well established but it is thought that patients become pharyngeal or conjunctival carriers of H. aegyptius, which is followed by spreading to the bloodstream. This hypothesis is supported by the isolation of from both the conjunctiva and oropharynx of documented BPF cases with H. aegyptius bacteremia. Possible virulence factors of H. aegyptius include lipooligosaccharides (LOS), capsular polysaccharides, pilus proteins , immunoglobulin A1 (IgA1), membrane associated proteins, and extracellular proteins. In a study conducted by Barbosa et al., a 60 kilodalton hemagglutinating extracellular product was suggested to be the major pathogenic factor linked to the hemorrhagic manifestations of BPF. This molecule was found to be absorbable by human O-type erythrocytes. Further research is being conducted to determine the mechanisms involved with the other virulence factors of H. aegyptius. The overall pathogenesis of BPF probably involves multiple steps and a number of bacterial factors.[14][4][15][13][2]

Diagnosis

A positive BPF diagnosis includes the clinical symptoms (mainly the fever, purpuric lesions, and rapid progression of the disease), isolation of Haemophilus Influenzae Biogroup aegyptius from blood, and negative laboratory tests for Neisseria meningitidis. The negative tests for Neisseria meningitidis rules out the possibility of the symptoms being caused by meningitis, since the clinical presentations of the two diseases are similar.[16][2][17][18]

Prevention

The basic method for control of the conjunctivitis includes proper hygiene and care for the affected eye. If the conjunctivitis is found to be caused by H. aegyptius Biogroup III then prompt antibiotic treatment preferably with rifampin(rifampicin) has been shown to prevent progression to BPF.[19] [20]

Treatment

H. aegyptius is not susceptible to the antibiotic eye drops that are being used to treat it; this treatment is ineffective because it treats only the local ocular infection, whereas if it progresses to BPF, systemic antibiotic treatment is required. Although BPF is susceptible to many commonly used antibiotics, including ampicillin, cefuroxime, cefotaxime, and chloramphenicol, by the time it is diagnosed the disease has progressed too much to be effectively treated.[21][4]

History

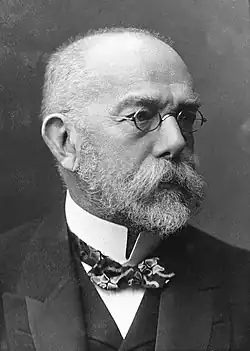

Brazilian purpuric fever was first recognized in 1984 in the town of Promissão, São Paulo State, Brazil. The disease was linked to a highly virulent clone of Haemophilus influenzae biogroup aegyptius.The bacterium itself, Haemophilus aegyptius, was discovered independently by Robert Koch in 1883 and J.E. Weeks in 1886.[17][4]

Notes

- 1.^ Non-review(PubMed indexed)

References

- ↑ "Brazilian purpuric fever (Concept Id: C0275703) - MedGen - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 20 June 2023.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Harrison, Lee H.; Simonsen, Vera; Waldman, Eliseu A. (October 2008). "Emergence and Disappearance of a Virulent Clone of Haemophilus influenzae Biogroup aegyptius, Cause of Brazilian Purpuric Fever". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 21 (4): 594–605. doi:10.1128/cmr.00020-08. PMC 2570154. PMID 18854482.

- ↑ "Photo 42973740, (c) Marshal Hedin, some rights reserved (CC BY-NC-SA), uploaded by Marshal Hedin · iNaturalist". iNaturalist. Retrieved 20 July 2025.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Cherry, James; Demmler-Harrison, Gail J.; Kaplan, Sheldon L.; Steinbach, William J.; Hotez, Peter J. (5 October 2013). Feigin and Cherry's Textbook of Pediatric Infectious Diseases E-Book: 2-Volume Set. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1689. ISBN 978-0-323-18660-5.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 "GIDEON platform". app.gideononline.com. Archived from the original on 21 October 2021. Retrieved 20 July 2025.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Musher, Daniel M. (1996). "Haemophilus Species". Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. ISBN 978-0-9631172-1-2. Archived from the original on 2025-03-30. Retrieved 2025-07-21.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "International Notes Brazilian Purpuric Fever -- Mato Grosso, Brazil". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 18 October 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2025.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Harrison, L H; da Silva, G A; Pittman, M; Fleming, D W; Vranjac, A; Broome, C V (1989). "Epidemiology and clinical spectrum of Brazilian purpuric fever. Brazilian Purpuric Fever Study Group" (PDF). Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 27 (4): 599–604. doi:10.1128/jcm.27.4.599-604.1989. ISSN 0095-1137. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-03-20. Retrieved 2025-07-26.

- ↑ Phillips, Zachary N.; Tram, Greg; Jennings, Michael P.; Atack, John M. (7 November 2019). "Closed Complete Annotated Genome Sequences of Five Haemophilus influenzae Biogroup aegyptius Strains". Microbiology Resource Announcements. 8 (45). doi:10.1128/mra.01198-19. ISSN 2576-098X. PMC 6838629. PMID 31699771.

- ↑ Ryan, Edward T.; Durand, Marlene (1 January 2011). "CHAPTER 135 - Ocular Disease". Tropical Infectious Diseases: Principles, Pathogens and Practice (Third ed.). W.B. Saunders. pp. 991–1016. ISBN 978-0-7020-3935-5. Archived from the original on 9 October 2023. Retrieved 17 July 2025.

- ↑ Falkow, Stanley; Rosenberg, Eugene; Schleifer, Karl-Heinz; Stackebrandt, Erko (12 October 2006). The Prokaryotes: Vol. 6: Proteobacteria: Gamma Subclass. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 1048. ISBN 978-0-387-25496-8.

- ↑ Klepzig, Kier D; Hartshorn, Jessica A; Tsalickis, Alexandra; Sheehan, Thomas N (1 January 2022). "Eye Gnat (Liohippelates, Diptera: Chloropidae) Biology, Ecology, and Management: Past, Present, and future". Journal of Integrated Pest Management. 13 (1). doi:10.1093/jipm/pmac015. ISSN 2155-7470. Archived from the original on 12 July 2022. Retrieved 23 July 2025.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Strouts, Fiona R.; Power, Peter; Croucher, Nicholas J.; Corton, Nicola; van Tonder, Andries; Quail, Michael A.; Langford, Paul R.; Hudson, Michael J.; Parkhill, Julian; Kroll, J. Simon; Bentley, Stephen D. (March 2012). "Lineage-specific virulence determinants of Haemophilus influenzae biogroup aegyptius". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 18 (3): 449–457. doi:10.3201/eid1803.110728. ISSN 1080-6059. PMC 3309571. PMID 22377449.

- ↑ Barenkamp, Stephen J. (1 January 2009). "OTHER HAEMOPHILUS SPECIES (APHROPHILUS, DUCREYI, HAEMOLYTICUS, INFLUENZAE BIOGROUP AEGYPTIUS, PARAHAEMOLYTICUS, AND PARAINFLUENZAE)". Feigin and Cherry's Textbook of Pediatric Infectious Diseases (Sixth ed.). W.B. Saunders. pp. 1756–1764. ISBN 978-1-4160-4044-6.

- ↑ Barbosa, S.F.C.; Hoshino-Shimizu, S.; das Gracas A. Alknin, M.; Goto, H. (2003). "Implications of Haemophilus influenzae Biogroup aegyptius Hemagglutinins in the Pathogenesis of Brazilian Purpuric Fever". Journal of Infectious Diseases. 188 (1): 74–80. doi:10.1086/375739. PMID 12825174.

- ↑ Turkington, Carol; Ashby, Bonnie (2007). The Encyclopedia of Infectious Diseases. Infobase Publishing. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-8160-7507-2.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "International Notes Brazilian Purpuric Fever: Haemophilus aegyptius Bacteremia Complicating Purulent Conjunctivitis". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 27 June 2025. Retrieved 15 July 2025.

- ↑ "Epidemiologic Notes and Reports Preliminary Report: Epidemic Fatal Purpuric Fever Among Children -- Brazil". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 9 July 2025. Retrieved 29 July 2025.

- ↑ "How to Prevent Pink Eye". Conjunctivitis (Pink Eye). 11 June 2025.

- ↑ Roy, Frederick Hampton; Fraunfelder, Frederick W.; Fraunfelder, Frederick T. (1 January 2008). Roy and Fraunfelder's Current Ocular Therapy. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-4160-2447-7.

- ↑ Ryan, EDWARD T.; Durand, MARLENE (1 January 2006). "Chapter 129 - Ocular Disease". Tropical Infectious Diseases (Second ed.). Churchill Livingstone. pp. 1554–1600. ISBN 978-0-443-06668-9.

Further reading

- McGillivary, G.; Tomaras, A.P.; Rhodes, E.R.; Actis, L.A (2005). "Cloning and sequencing of a genomic island found in the Brazilian Purpuric Fever clone of Haemophilis influenzae Biogroup aegyptius". Infection and Immunity. 73 (4): 1927–1938. doi:10.1128/IAI.73.4.1927-1938.2005. PMC 1087403. PMID 15784532.

- Rubin, L.G.; St. Geme III, J.W. (1993). "Role of Lipooligosaccharide in Virulence of the Brazilian Purpuric Fever Clone of Haemophilus influenzaeBiogroup aegyptius for Infant Rats". Infection and Immunity. 61 (2): 650–655. doi:10.1128/IAI.61.2.650-655.1993. PMC 302776. PMID 8093694.

External links

| Classification |

|---|