Yersiniosis

| Yersinia enterocolitica | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Yersinia infection[1] | |

| |

| |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, fever[3] |

| Complications | Cholangitis,septicemia,toxic megacolon,hepatic abscess[3] |

| Causes | Yersinia enterocolitica[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Stool culture[3] |

| Differential diagnosis | Diverticulitis,Inflammatory bowel disease[3] |

| Treatment | Aminoglycosides or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole[3] |

Yersiniosis is an infectious disease caused by a bacterium of the genus Yersinia. Infection with Y. enterocolitica occurs most often in young children.[3][4][5]

The infection is thought to be contracted through the consumption of undercooked meat products, unpasteurized milk, or water contaminated by the bacteria. It has been also sometimes associated with handling raw chitterlings.[6][7] Another bacterium of the same genus, Yersinia pestis, is the cause of Plague.[8]

As to management we find that the drugs of choice are aminoglycosides or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole[3]

Signs and symptoms

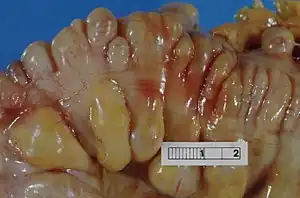

Infection with Y. enterocolitica can cause a variety of symptoms depending on the age of the person infected. Common symptoms in children are fever, abdominal pain, and diarrhea, which is often bloody. Symptoms typically develop 4 to 7 days after exposure and may last 1 to 3 weeks or longer. In older children and adults, right-sided abdominal pain and fever may be the predominant symptoms, and may be confused with appendicitis. In a small proportion of cases, complications such as skin rash, joint pains, ileitis, erythema nodosum, and sometimes sepsis, acute arthritis[9] or the spread of bacteria to the bloodstream (bacteremia) can occur.

Complications

In terms of the complications of Yersiniosis we find the following:[3]

- Paralytic ileus

- Cholangitis

- Septicemia

- Toxic megacolon

- Hepatic abscess

- Splenic abscess

- Renal abscess

Cause

The etiology of Yersiniosis is Yersinia enterocolitica, humans are hosts who do not contribute to the pathogens life cycle [3] Most people become infected by eating contaminated food, especially raw or undercooked pork, or through contact with a person who has prepared a pork product, such as chitlins.[5] For example, babies and infants can be infected if their caretakers handle contaminated food and then do not wash their hands properly before handling the child or the child's toys, bottles, or pacifiers.[5] People occasionally become infected after drinking contaminated milk or untreated water, or after contact with infected animals or their feces.[5] On rare occasions, people become infected through person-to-person contact.[5] For example, caretakers can become infected if they do not wash their hands properly after changing the diaper of a child with yersiniosis.[5] Even more rarely, people may become infected through contaminated blood during a transfusion.[5]

Risk factors

In terms of risk factors that may increase the possibility of an individual acquiring Yersiniosis is as follows:[10][11]

- Poor hygiene

- Contaminated food

Mechanism

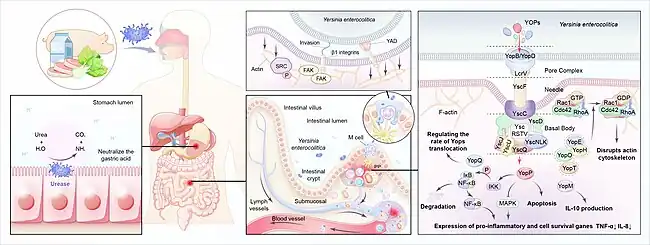

In terms of the mechanism of Yersiniosis we find that it involves the invasion of epithelial cells,as well as the colonization of lymphoid tissue, and spread to other organs. Among the pathogenic properties of Yersinia are chromosomally mediated effects and plasmid-mediated mechanisms[3][12]

Diagnosis

As to the diagnosis of Yersiniosis we find that the isolation of the organism can be done from:[11]

- Stool

- Blood

- Cerebrospinal fluid

- Mesenteric lymph nodes

- Peritoneal fluid

- Throat swab

Differential diagnosis

In terms of the DDX we find that the following should be considered:[3]

- Diverticulitis

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Medication-associated colitis

- Cancer of colon

- Ischemic colitis

- HIV(developing countries)

Treatment

Treatment for gastroenteritis due to Y. enterocolitica is not needed in the majority of cases. Severe infections with systemic involvement (sepsis or bacteremia) often requires aggressive antibiotic therapy; the drugs of choice are aminoglycosides or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Alternatives include cefotaxime, fluoroquinolones, and co-trimoxazole.[3][13][14]

Epidemiology

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that infections with Yersinia enterocolitica cause almost 117,000 illnesses, 640 hospitalizations, and 35 deaths in the United States every year.[5]

In 2011, there were 7,017 diagnosed cases of yersiniosis in the European Union.[4] This was a 3.5% increase compared to the prior year.[4]

In 2011, there were 257 diagnosed cases of yersiniosis in Poland.[4]

In 2012 in Poland, there was a drop to 231 reported yersiniosis cases.[4]

Children are infected more often than adults, and the infection is more common in the winter.[5]

-

![Yersinia enterocolitica infections in Germany, 2001-2008[15]](./_assets_/0c70a452f799bfe840676ee341124611/Yersiniosis_epidemiology.jpg) Yersinia enterocolitica infections in Germany, 2001-2008[15]

Yersinia enterocolitica infections in Germany, 2001-2008[15] -

![Geographical distribution of Yersiniosis[2]](./_assets_/ba48700f93e6ccab7a94adacb8f4c793/Yersiniosis.gif) Geographical distribution of Yersiniosis[2]

Geographical distribution of Yersiniosis[2]

History

As to history 1975 the first case of Yersinia enterocolitica was initially described in Netherlands in the year 1975; many additional cases have been reported worldwide. Y. enterocolitica was first described in 1934 as the cause of an individuals facial abscess[16][17]

Research

A 2024 article indicates that the biggest breakthrough in Yersiniosis diagnostics is the widespread use of culture-independent diagnostic test, especially syndromic gastrointestinal panels, which have significantly boosted detection rates[18]

References

- ↑ "Yersiniosis (Concept Id: C0043407) - MedGen - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 5 September 2024. Retrieved 17 January 2025.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Shoaib, Muhammad; Shehzad, Aamir; Raza, Husnain; Niazi, Sobia; Khan, Imran Mahmood; Akhtar, Wasim; Safdar, Waseem; Wang, Zhouping (9 December 2019). "A comprehensive review on the prevalence, pathogenesis and detection of Yersinia enterocolitica". RSC Advances. 9 (70): 41010–41021. Bibcode:2019RSCAd...941010S. doi:10.1039/C9RA06988G. ISSN 2046-2069. PMC 9076465. PMID 35540058.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 Aziz, Muhammad; Yelamanchili, Varun S. (2023). "Yersinia Enterocolitica". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 29763012. Archived from the original on 3 February 2023. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Bancerz-Kisiel, Agata; Szweda, Wojciech (4 September 2015). "Yersiniosis – zoonotic foodborne disease of relevance to public health". Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine. 22 (3): 397–402. doi:10.5604/12321966.1167700. PMID 26403101.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 "Questions and Answers". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1 August 2019. Archived from the original on 22 April 2023. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ Jones TF (August 2003). "From pig to pacifier: chitterling-associated yersiniosis outbreak among black infants". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 9 (8): 1007–9. doi:10.3201/eid0908.030103. PMC 3020614. PMID 12967503.

- ↑ Lee, LA.; Gerber, AR.; Lonsway, DR.; Smith, JD.; Carter, GP.; Puhr, ND.; Parrish, CM.; Sikes, RK.; Finton, RJ.; Tauxe, RV. (1990). " Yersinia enterocolitica O:3 infections in infants and children, associated with the household preparation of chitterlings". New England Journal of Medicine. 322 (14): 984–987. doi:10.1056/NEJM199004053221407. PMID 2314448.

- ↑ Ryan, KJ; Ray, CG, eds. (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 484–88. ISBN 978-0-8385-8529-0.

- ↑ "Yersiniosis". Medical Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2018-12-21. Retrieved 2013-01-28.

- ↑ "About Yersinia Infection". Yersinia Infection (Yersiniosis). 4 November 2024. Archived from the original on 10 February 2025. Retrieved 11 February 2025.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Clinical Overview of Yersiniosis". Yersinia Infection (Yersiniosis). 16 May 2024. Archived from the original on 25 January 2025. Retrieved 22 January 2025.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Fang, Xue; Kang, Le; Qiu, Yi-Fan; Li, Zhao-Shen; Bai, Yu (2023). "Yersinia enterocolitica in Crohn's disease". Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 13. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2023.1129996. ISSN 2235-2988. PMC 10031030. PMID 36968108.

- ↑ Torok E. Oxford MHandbook of Infect Dis and Microbiol, 2009

- ↑ Collins FM (1996). Baron S; et al. (eds.). Pasteurella, and Francisella. In: Barron's Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). Univ of Texas Medical Branch. ISBN 0-9631172-1-1. (via NCBI Bookshelf).

- ↑ Rosner, Bettina M; Stark, Klaus; Werber, Dirk (December 2010). "Epidemiology of reported Yersinia enterocolitica infections in Germany, 2001-2008". BMC Public Health. 10 (1): 337. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-337. PMC 2905328. PMID 20546575.

- ↑ Bottone, E. J. (April 1997). "Yersinia enterocolitica: the charisma continues". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 10 (2): 257–276. doi:10.1128/CMR.10.2.257. ISSN 0893-8512. PMC 172919. PMID 9105754.

- ↑ Sabina, Yeasmin; Rahman, Atiqur; Ray, Ramesh Chandra; Montet, Didier (2011). "Yersinia enterocolitica : Mode of Transmission, Molecular Insights of Virulence, and Pathogenesis of Infection". Journal of Pathogens. 2011: 1–10. doi:10.4061/2011/429069. PMC 3335483. PMID 22567333.

- ↑ Ray, Logan C; Payne, Daniel C; Rounds, Joshua; Trevejo, Rosalie T; Wilson, Elisha; Burzlaff, Kari; Garman, Katie N; Lathrop, Sarah; Rissman, Tamara; Wymore, Katie; Wozny, Sophia; Wilson, Siri; Francois Watkins, Louise K; Bruce, Beau B; Weller, Daniel L (3 June 2024). "Syndromic Gastrointestinal Panel Diagnostic Tests Have Changed our Understanding of the Epidemiology of Yersiniosis —Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network, 2010-2021". Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 11 (6). doi:10.1093/ofid/ofae199. Retrieved 5 October 2025.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |