Tick paralysis

| Tick paralysis | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Tick toxicosis[1] | |

| |

| Australian paralysis tick before and after feeding | |

| Specialty | Emergency medicine |

| Symptoms | Tiredness, poor ability to walk, muscle weakness[2] |

| Complications | Respiratory failure[2] |

| Usual onset | 2 to 7 days with an attached tick[3][2] |

| Duration | Until a few hours to days after removal[2] |

| Causes | Certain types of tick bites[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Thorough examination[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Guillain-Barre syndrome, botulism, poliomyelitis, myasthenia gravis, hypokalemia[2][4] |

| Treatment | Supportive care, removing the tick[2] |

| Prognosis | Good with treatment[2] |

| Frequency | Rare[4] |

Tick paralysis is a neurological condition that begins with tiredness, and progresses to poor ability to walk and muscle weakness as a result of certain tick bites.[2] Weakness starts in the legs and moves up the body.[2] Fever and rash do not generally occur.[2] Onset generally requires the tick to be attached for two to seven days.[2][3] Complications can include respiratory failure.[2]

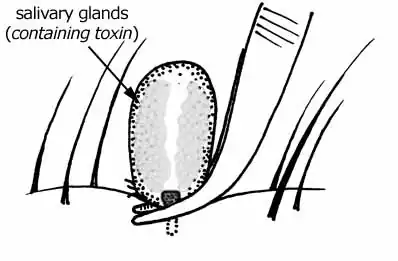

While more than 40 types of type ticks are implicated, in North America the American dog tick and Rocky Mountain wood tick are most commonly involved while in Australia it is the Australian paralysis tick.[2] The underlying mechanism involves neurotoxin produced in female tick's salivary gland.[2] Diagnosis is by a thorough examination to find the tick.[2] It is a type of tick-borne illness.[2]

Treatment involves supportive care and removing the tick.[2] Supportive care may include mechanical ventilation.[2] Prevention is by avoiding tick bites such as by applying permethrin to clothing and using DEET.[2] Full recovery occurs within a few hours to days of the ticks removal.[2]

Tick paralysis is rare.[4] Cases, when they do occur, are most frequent in North America and Australia.[2] Children are more commonly affected than adults.[2] The condition was first described in the 1800s.[2] Other animals may also be affected.[2]

Signs and symptoms

Onset of symptoms requires the tick to be attached for about a week. Symptoms begin with weakness in both legs that progresses to paralysis. The paralysis ascends to the trunk, arms, and head within hours and may lead to respiratory failure and death. The disease can present as acute ataxia without muscle weakness.[2][5][6][3]

Patients may report minor sensory symptoms, such as local numbness, but constitutional signs are usually absent. Deep tendon reflexes are usually decreased or absent, and ophthalmoplegia and bulbar palsy can occur.[7][8][1]

Cause

The two ticks most commonly associated with North American tick paralysis are the Rocky Mountain wood tick (Dermacentor andersoni) and the American dog tick (Dermacentor variabilis).[9]

However, to date, 43 tick species have been implicated in human disease around the world.[9]

Most North American cases of tick paralysis occur from April to June, when adult Dermacentor ticks emerge from hibernation and actively seek hosts.[10]

In Australia, tick paralysis is caused by the tick Ixodes holocyclus. Prior to 1989, 20 fatal cases were reported in Australia.[11]

-

Dermacentor andersoni

Dermacentor andersoni -

Engorged tick on the hairline.

Engorged tick on the hairline.

Pathogenesis

Tick paralysis is believed to be due to toxins found in the tick's saliva that enter the bloodstream while the tick is feeding.Tick paralysis occurs when an engorged and gravid female tick produces a neurotoxin in its salivary glands and transmits it to its host during feeding. Experiments have indicated that the greatest amount of toxin is produced at about one weeks time of attachment, although the timing may vary depending on the species of tick.[12][13][14]

Unlike Lyme disease, ehrlichiosis, and babesiosis, which are caused by parasites in their hosts long after the offending tick is gone, tick paralysis is chemically induced by the tick and therefore usually only continues in its presence. Once the tick is removed, symptoms usually diminish rapidly. However, in some cases, profound paralysis can develop and even become fatal before anyone becomes aware of a tick's presence.[15][14]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on symptoms and upon finding an embedded tick, usually on the scalp.In the absence of a tick, the differential diagnosis includes Guillain–Barré syndrome.[16][2]

Electromyographic (EMG) studies usually show a variable reduction in the amplitude of compound muscle action potentials, but no abnormalities of repetitive nerve stimulation studies. These appear to result from a failure of acetylcholine release at the motor nerve terminal level. There may be subtle abnormalities of motor nerve conduction velocity and sensory action potentials.[17][18]

Differential diagnosis

In terms of the differential diagnosis for Tick paralysis we find the following should be considered:[2]

- Guillain-Barre syndrome

- Botulism

- Myasthenia gravis

- Poliomyelitis

Prevention

Individuals should take precautions when entering tick-infested areas, particularly in the spring and summer months. Preventive measures include avoiding trails that are overgrown with bushy vegetation, wearing light-coloured clothes that allow one to see the ticks more easily, and wearing long pants and closed-toe shoes. Tick repellents containing DEET (N,N, diethyl-m-toluamide) are only marginally effective and can be applied to skin or clothing. Rarely, severe reactions can occur in some people who use DEET-containing products. Young children may be especially vulnerable to these adverse effects. Permethrin, which can only be applied to clothing, is much more effective in preventing tick bites. Permethrin is not a repellent but rather an insecticide; it causes ticks to curl up and fall off the protected clothing.[2][19][11]

Treatment

Removal of the offending tick usually results in resolution of symptoms within several hours to days. The tick is best removed by grasping it as close to the skin as possible and pulling in a firm steady manner. Because the toxin lies in the tick's salivary glands, care must be taken to remove the entire tick (including the head), or symptoms may persist.[2][20]

In the case of Australian Ixodes holocyclus tick, after the tick is removed paralysis may worsen which would therefore need observation for respiratory compromise.If breathing is impaired due to the tick bite, oxygen therapy may be needed[21][2]

-

a) Paralysis tick attached to right temporal bulbar conjunctiva b)surgical removal of the larval tick

a) Paralysis tick attached to right temporal bulbar conjunctiva b)surgical removal of the larval tick -

Tick removal. Compressing the body of the tick could cause more toxins to be injected into the host.

Tick removal. Compressing the body of the tick could cause more toxins to be injected into the host.

Prognosis

If the tick is not removed, the toxin can be fatal. A 1969 study of children reported mortality rates of 10 – 12 percent,[22] mostly due to respiratory paralysis.

Unlike the toxin of other tick species, the toxin of Ixodes holocyclus (Australian paralysis tick) may still be fatal even if the tick is removed.[23]

Epidemiology

In terms of the epidemiology we find that batches of cases have been encountered in several countries. It has been identified in Argentina, Canada, and in many regions of the United States.[2]

Although tick paralysis is of concern in domestic animals and livestock in the United States, human cases are rare and usually occur in very young children.[24]

-

![Distribution of the American dog tick (D. varaiabilis) in the United States.[25]](./_assets_/ba48700f93e6ccab7a94adacb8f4c793/Screenshot_10-7-2024_17124_www.cdc.gov.jpg) Distribution of the American dog tick (D. varaiabilis) in the United States.[25]

Distribution of the American dog tick (D. varaiabilis) in the United States.[25] -

Distribution of Australian paralysis tick

Distribution of Australian paralysis tick

Society and culture

On television this condition has been explored in the following TV shows:

- Hart of Dixie, Season 1, Episode 2, a patient is diagnosed with tick paralysis who has been deer hunting.[26]

- Emergency!, Season 5, Episode 4, "Equipment" (first aired Oct. 4, 1975), Dr. Joe Early diagnoses a young boy who has fallen from a tree with tick paralysis, after eliminating polio as a cause.[27]

- House, Season 2, Episode 16, "Safe", Dr House diagnoses a patient (played by Michelle Trachtenberg) with tick paralysis.[28]

- Remedy, Season 1 Episode 7, "Tomorrow, the Green Grass", Rebecca is diagnosed with tick paralysis.[29]

Research

Although several attempts have been made to isolate and identify the neurotoxin since the first isolation in 1966, the exact structure of the toxin has still not been published.[30] The 40-80 kDa protein fraction contains the toxin.[31]

The neurotoxin structure and gene, at least for the tick species Ixodes holocyclus have since been identified and are called holocyclotoxins after the species. At least three members (HT-1,[32] HT-3,[33] and HT-12[34]) trigger paralysis by presynaptic inhibition of neurotransmitter release via a calcium dependent mechanism resulting in a reduction of quantal content, and loss of effective neuromuscular synaptic transmission.[35]

Other animals

For affected animals, food and water intake can worsen the outcome, as the toxin can prevent the animal from swallowing properly. People who find a tick on their animal, are advised to remove it immediately and seek veterinary assistance if the animal shows any signs of illness. The tick can be placed in a tightly sealed plastic bag and taken to a veterinarian for identification.[36][37]

Notes

- 1.^ Due to the possible wide range of signs and symptoms a case report was added

References

- ↑ Mans, B. J.; Gothe, R.; Neitz, A. W. H. (October 2004). "Biochemical perspectives on paralysis and other forms of toxicoses caused by ticks". Parasitology. 129 (S1): S95 – S111. doi:10.1017/S0031182003004670. ISSN 1469-8161. PMID 15938507. Archived from the original on 2022-10-31. Retrieved 2024-06-30.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 2.21 2.22 2.23 2.24 2.25 2.26 2.27 2.28 2.29 2.30 2.31 2.32 Simon, LV; West, B; McKinney, WP (January 2022). "Tick Paralysis". StatPearls. PMID 29262244.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Pecina, CA (November 2012). "Tick paralysis". Seminars in Neurology. 32 (5): 531–2. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1334474. PMID 23677663.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 "Tick Paralysis - Injuries; Poisoning". Merck Manuals Professional Edition. Archived from the original on 30 October 2021. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ↑ "Tick paralysis: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Archived from the original on 27 September 2023. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

- ↑ Edlow, Jonathan A.; McGillicuddy, Daniel C. (September 2008). "Tick Paralysis". Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 22 (3): 397–413. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2008.03.005. PMID 18755381. Archived from the original on 2024-04-24. Retrieved 2024-07-05.

- ↑ Li, Zhongzeng; Turner, Robert P. (1 October 2004). "Pediatric tick paralysis: Discussion of two cases and literature review". Pediatric Neurology. 31 (4): 304–307. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2004.05.005. ISSN 0887-8994. Archived from the original on 7 July 2024. Retrieved 6 July 2024.

- ↑ Chagnon, Sarah L.; Naik, Monica; Abdel-Hamid, Hoda (18 March 2014). "Child Neurology: Tick paralysis: A diagnosis not to miss". Neurology. 82 (11): e91-3. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000000216. ISSN 0028-3878. PMID 24638220. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Gothe R, Kunze K, Hoogstraal H (1979). "The mechanisms of pathogenicity in the tick paralyses". J Med Entomol. 16 (5): 357–69. doi:10.1093/jmedent/16.5.357. PMID 232161.

- ↑ Dworkin MS, Shoemaker PC, Anderson D (1999). "Tick paralysis: 33 human cases in Washington state, 1946–1996". Clin Infect Dis. 29 (6): 1435–9. doi:10.1086/313502. PMID 10585792.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Masina, S; Broady, K.W (April 1999). "Tick paralysis: development of a vaccine". International Journal for Parasitology. 29 (4): 535–541. doi:10.1016/S0020-7519(99)00006-5. PMID 10428629. Archived from the original on 2024-04-15. Retrieved 2024-07-11.

- ↑ Pienaar, Ronel; Neitz, Albert W. H.; Mans, Ben J. (14 May 2018). "Tick Paralysis: Solving an Enigma". Veterinary Sciences. 5 (2): 53. doi:10.3390/vetsci5020053. ISSN 2306-7381. PMC 6024606. PMID 29757990.

- ↑ Murnaghan, Maurice F. (12 February 1960). "Site and Mechanism of Tick Paralysis". Science. 131 (3398): 418–419. Bibcode:1960Sci...131..418M. doi:10.1126/science.131.3398.418. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 14425361. Archived from the original on 9 July 2024. Retrieved 7 July 2024.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Drutz, Jan E. (1 January 2009). "CHAPTER 241 - ARTHROPODS". Feigin and Cherry's Textbook of Pediatric Infectious Diseases (Sixth ed.). W.B. Saunders. pp. 3033–3039. ISBN 978-1-4160-4044-6. Archived from the original on 9 July 2024. Retrieved 7 July 2024.

- ↑ Gunn, Alan; Pitt, Sarah J. (30 March 2012). Parasitology: An Integrated Approach. John Wiley & Sons. p. 148. ISBN 978-1-119-94508-6. Archived from the original on 9 July 2024. Retrieved 8 July 2024.

- ↑ Diaz, James Henry (March 2010). "A 60-year meta-analysis of tick paralysis in the United States: a predictable, preventable, and often misdiagnosed poisoning". Journal of Medical Toxicology: Official Journal of the American College of Medical Toxicology. 6 (1): 15–21. doi:10.1007/s13181-010-0028-3. ISSN 1556-9039. PMC 3550436. PMID 20186584.

- ↑ Lin, Jenny; Verma, Sumit (June 2016). "Electrodiagnostic Abnormalities in Tick Paralysis: A Case Report and Review of Literature". Journal of Clinical Neuromuscular Disease. 17 (4): 215–219. doi:10.1097/CND.0000000000000103. ISSN 1537-1611. PMID 27224437. Archived from the original on 2024-07-12. Retrieved 2024-07-10.

- ↑ Vedanarayanan, V.; Sorey, W. H.; Subramony, S. H. (June 2004). "Tick Paralysis". Seminars in Neurology. 24 (2): 181–184. doi:10.1055/s-2004-830905. ISSN 0271-8235. Archived from the original on 2024-07-23. Retrieved 2024-07-17.

- ↑ "Preventing Tick Bites". Ticks. 11 June 2024. Archived from the original on 2 July 2024. Retrieved 9 July 2024.

- ↑ Needham GR (1985). "Evaluation of five popular methods for tick removal". Pediatrics. 75 (6): 997–1002. doi:10.1542/peds.75.6.997. PMID 4000801. S2CID 23208238.

- ↑ "Tick Paralysis - Tick Paralysis". Merck Manual Professional Edition. Archived from the original on 8 December 2023. Retrieved 11 July 2024.

- ↑ Schmitt N, Bowmer EJ, Gregson JD (1969). "Tick paralysis in British Columbia". Can Med Assoc J. 100 (9): 417–21. PMC 1945728. PMID 5767835.

- ↑ Hall-Mendelin, S; Craig, S B; Hall, R A; O'Donoghue, P; Atwell, R B; Tulsiani, S M; Graham, G C (March 2011). "Tick paralysis in Australia caused by Ixodes holocyclus Neumann". Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology. 105 (2): 95–106. doi:10.1179/136485911X12899838413628. ISSN 0003-4983. PMC 4084664. PMID 21396246.

- ↑ Diaz, James H. (November 2015). "A Comparative Meta-Analysis of Tick Paralysis in the United States and Australia". Clinical Toxicology (Philadelphia, Pa.). 53 (9): 874–883. doi:10.3109/15563650.2015.1085999. ISSN 1556-9519. PMID 26359765. Archived from the original on 4 July 2024. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

- ↑ "Where Ticks Live". Ticks. 8 July 2024. Archived from the original on 9 July 2024. Retrieved 10 July 2024.

- ↑ Ensler, Jason (3 October 2011). "Parades & Pariahs". Hart of Dixie. Archived from the original on 6 October 2022. Retrieved 9 July 2024.

- ↑ "IMDB". IMDb. Archived from the original on 2021-11-26. Retrieved 2022-02-05.

- ↑ "House MD Episode Guide: Season Two #216 'Safe'". housemd-guide.com. Archived from the original on May 9, 2012. Retrieved August 11, 2012.

- ↑ "Remedy Episode Guide, Show Summary and Schedule: Is Remedy Renewed or Cancelled?". TV Calendar. Archived from the original on 28 July 2021. Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- ↑ Doube B. M. (1975). "Cattle and Paralysis Tick Ixodes-Holocyclus". Australian Veterinary Journal. 51 (11): 511–515. doi:10.1111/j.1751-0813.1975.tb06901.x. PMID 1220655.

- ↑ B. F. Stone; K. C. Binnington; M. Gauci; J. H. Aylward (1989). "Tick/host interactions forIxodes holocyclus: Role, effects, biosynthesis and nature of its toxic and allergenic oral secretions". Experimental and Applied Acarology. 7 (1): 59–69. doi:10.1007/BF01200453. PMID 2667920. S2CID 23861588.

- ↑ "Ixodes holocyclus holocyclotoxin-1 (HT1) mRNA, complete cds - Nucleotide - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. 27 October 2004. Archived from the original on 2018-07-29. Retrieved 2018-07-29.

- ↑ "Ixodes holocyclus holocyclotoxin 3 (HT3) mRNA, complete cds - Nucleotide - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2018-07-29. Retrieved 2018-07-29.

- ↑ "Ixodes holocyclus holocyclotoxin 12 (HT12) mRNA, complete cds - Nucleotide - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2018-07-29. Retrieved 2018-07-29.

- ↑ Chand, Kirat K.; Lee, Kah Meng; Lavidis, Nickolas A.; Rodriguez-Valle, Manuel; Ijaz, Hina; Koehbach, Johannes; Clark, Richard J.; Lew-Tabor, Ala; Noakes, Peter G. (2016-07-08). "Tick holocyclotoxins trigger host paralysis by presynaptic inhibition". Scientific Reports. 6 (1): 29446. Bibcode:2016NatSR...629446C. doi:10.1038/srep29446. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 4937380. PMID 27389875.

- ↑ Cannon, Michael. "Envenomation: Tick Paralysis" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 16, 2018. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

- ↑ O'Keefe, Dr Janette. "Australian Paralysis Tick" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on March 23, 2018. Retrieved June 9, 2018.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |