Waterhouse–Friderichsen syndrome

| Waterhouse–Friderichsen syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Hemorrhagic adrenalitis[1] | |

| |

| |

| Specialty | Infectious disease, nephrology |

| Symptoms | Fever,joint pain,headache,vomiting[2] |

| Causes | Bacterial infection(Neisseria meningitidis)[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Clinical assessment, lab tests, and imaging[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Septic shock and congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency[2] |

| Treatment | Antibiotic, corticosteroids[2] |

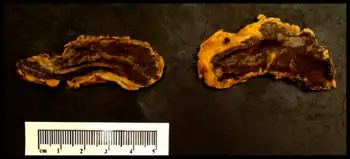

Waterhouse–Friderichsen syndrome (WFS) is defined as adrenal gland failure due to bleeding into the adrenal glands, commonly caused by severe bacterial infection. Typically, it is caused by Neisseria meningitidis.[3][1]

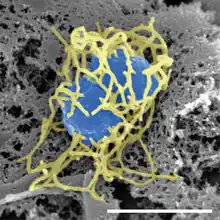

The bacterial infection leads to massive bleeding into one or (usually) both adrenal glands.[4] It is characterized by overwhelming bacterial infection meningococcemia leading to massive blood invasion, organ failure, coma, low blood pressure and shock, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) with widespread purpura, rapidly developing adrenocortical insufficiency and death.[5][1][2]

Ceftriaxone is an antibiotic commonly employed today for treatment[6]

Signs and symptoms

Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome can be caused by a number of different organisms, when caused by Neisseria meningitidis, WFS is considered the most severe form of meningococcal sepsis. The onset of the illness is nonspecific with:[1][2][5]

- Headache

- Vomit

- Fever

- Muscle pain

- Rash

- DIC

- Dizziness

- Hypotension

Causes

Multiple species of bacteria can be associated with the condition:

- Meningococcus is another term for the bacterial species Neisseria meningitidis; blood infection with said species usually underlies WFS. While many infectious agents can infect the adrenals, an acute, selective infection is usually meningococcus.[2][7]

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa can also cause WFS.[1]

- WFS can also be caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae infections, a common bacterial pathogen typically associated with meningitis in the adult and elderly population.[4]

- Mycobacterium tuberculosis could also cause WFS. Tubercular invasion of the adrenal glands could cause hemorrhagic destruction of the glands and cause mineralocorticoid deficiency[8]

Mechanism

The pathogenesis of Waterhouse–Friderichsen syndrome is not clear[2]

Diagnosis

Diagnostic criteria are based on clinical features of adrenal insufficiency as well as identifying the causal agent. If the causal agent is suspected to be meningitis a lumbar puncture is performed. If the causal agent is suspected to be bacterial a blood culture and complete blood count is performed. An adrenocorticotropic hormone stimulation test can be performed to assess adrenal function.[1][2][5]

Differential diagnosis

In terms of the DDx we find the following should be considered:[2]

Prevention

Routine vaccination against meningococcus is recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for all 11- to 18-year-olds and people who have poor splenic function (who, for example, have had their spleen removed or who have sickle-cell disease which damages the spleen), or who have certain immune disorders, such as a complement deficiency.[9]

Treatment

Fulminant infection from meningococcal bacteria in the bloodstream is a medical emergency and requires emergent treatment with vasopressors, fluid resuscitation, and appropriate antibiotics. Benzylpenicillin was once the drug of choice with chloramphenicol as a good alternative in allergic patients. Ceftriaxone is an antibiotic commonly employed today. Hydrocortisone can sometimes reverse the adrenal insufficiency.[2][1][5]

Prognosis

In terms of the prognosis we find that it depends on how severe the illness is; 15 percent with acute bilateral adrenal bleeding face a fatal outcome. If theres a delay in diagnosis and treatment, the fatality rate can be 50 percent[2]

Epidemiology

In term of the incidence it is ~1 percent in post-mortem studies of patients with severe sepsis. Additionally, it is more common in children, with the highest incidence between 6 months and 1 year of age, and also reported during adolescence[2][10]

History

Waterhouse–Friderichsen syndrome is named after Rupert Waterhouse (1873–1958), an English physician, and Carl Friderichsen (1886–1979), a Danish pediatrician, who wrote papers on the syndrome, which had been previously described.[11][12]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 "Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome". MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 2001-08-20. Retrieved 2014-04-12.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 Karki, Bhesh R.; Sedhai, Yub Raj; Bokhari, Syed Rizwan A. (2025). "Waterhouse-Friderichsen Syndrome". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 31855354. Archived from the original on 2025-02-07. Retrieved 2025-06-28.

- ↑ "Waterhouse–Friderichsen syndrome". Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD). Archived from the original on 9 May 2009. Retrieved 14 December 2012.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Kumar V, Abbas A, Fausto N (2005). Robins and Coltran: Pathological Basis of Disease (7th ed.). Elsevier. pp. 1214–5. ISBN 978-0-7216-0187-8.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Rijal, Rishikesh; Kandel, Kamal; Aryal, Barun Babu; Asija, Ankush; Shrestha, Dhan Bahadur; Sedhai, Yub Raj (1 January 2024). "Chapter Thirteen - Waterhouse–Friderichsen syndrome, septic adrenal apoplexy". Vitamins and Hormones. Vol. 124. Academic Press. pp. 449–461. doi:10.1016/bs.vh.2023.06.001. ISBN 978-0-443-19400-9. PMID 38408808. Archived from the original on 1 March 2024. Retrieved 11 July 2025.

- ↑ Nahata, M. C.; Barson, W. J. (December 1985). "Ceftriaxone: a third-generation cephalosporin". Drug Intelligence & Clinical Pharmacy. 19 (12): 900–906. doi:10.1177/106002808501901203. ISSN 0012-6578. PMID 3910386. Archived from the original on 2025-01-19. Retrieved 2025-07-16.

- ↑ Rausch-Phung, Elizabeth A.; Hall, Walter A.; Ashong, Derrick (2025). "Meningococcal Disease (Neisseria meningitidis Infection)". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 31751039. Archived from the original on 27 February 2023. Retrieved 8 July 2025.

- ↑ Vinnard, Christopher; Blumberg, Emily A. (24 February 2017). "Endocrine and Metabolic Aspects of Tuberculosis". Microbiology Spectrum. 5 (1): 10.1128/microbiolspec.tnmi7–0035–2016. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.tnmi7-0035-2016. PMC 5785104. PMID 28233510.

- ↑ Rosa D, Pasqualotto A, de Quadros M, Prezzi S (2004). "Deficiency of the eighth component of complement associated with recurrent meningococcal meningitis--case report and literature review" (PDF). Braz J Infect Dis. 8 (4): 328–30. doi:10.1590/S1413-86702004000400010. PMID 15565265. Archived from the original on 2022-10-08. Retrieved 2022-09-25.

- ↑ Bissonnette, Bruno; Luginbuehl, Igor; Engelhardt, Thomas (2019). "Waterhouse-Friderichsen Syndrome". Syndromes: Rapid Recognition and Perioperative Implications. McGraw-Hill Education. Archived from the original on 15 September 2024. Retrieved 12 July 2025.

- ↑ Waterhouse R (1911). "A case of suprarenal apoplexy". Lancet. 1 (4566): 577–8. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)60988-7.

- ↑ Friderichsen C (1918). "Nebennierenapoplexie bei kleinen Kindern". Jahrbuch für Kinderheilkunde und Physische Erziehung. 87: 109–25.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |