Pott's disease

| Pott's disease | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Pott disease, spinal tuberculosis[1] | |

| |

| Tuberculosis of the spine | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease,orthopedic surgeon |

| Symptoms | Back pain, swelling, stiffness[2] |

| Complications | Abscess, spinal instability[2] |

| Causes | Tuberculosis[2] |

| Risk factors | HIV, weakened immune system[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Radiograph, MRI[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Atypical bacteria, fungi, spirochetes[2] |

| Treatment | Combination of antibiotics for 6 months(or more)[2] |

| Named after | Percivall Pott[2] |

Pott's disease is tuberculosis of the spine,[3][4] usually due to spread via the blood from the lungs. Spread of infection from the lumbar vertebrae to the psoas muscle, causing abscesses, is not uncommon.[5][2][4]

The lower thoracic and upper lumbar vertebrae areas of the spine are most often affected.[2][4]

It causes a kind of tuberculous arthritis of the intervertebral joints. The infection can spread from two adjacent vertebrae into the adjoining intervertebral disc space. If only one vertebra is affected, the disc is normal, but if two are involved, the disc, which is avascular, cannot receive nutrients, and collapses. In a process called caseous necrosis, the disc tissue dies, leading to vertebral narrowing and eventually to vertebral collapse and spinal damage. A dry soft-tissue mass often forms and superinfection is rare.

Management involves medications and occasionally surgery.[6] It is named for British surgeon Percivall Pott who first described the symptoms in 1799.[7]

Signs and symptoms

The onset of symptoms is gradual and disease progresses slowly.[8] The duration of symptoms before diagnosis ranges from 2 weeks to year(s). The average period was at least 12 months, but it has recently decreased to 3 and 6 months.[8]

Presentation depends on disease stage, location, and complications such as neurological deficits and abscesses.[8] Further presentations include:[2]

Complications

Certain complications can cause abscesses to form, which puts the individual at a higher risk of spinal cord damage and possible paraplegia.[9] The lesions responsible for abscesses occur more frequently in younger patients as their spine is highly vascularized compared to adults.[9] Involvement of the front part of the spine or areas not involving the bone initially spares it and the disc of the spinal column.[9] However, abscess formation allows disease to spread over multiple contiguous vertebrae using the front longitudinal ligament.[9] These abscesses are granulomatous and, as they expand, lift the periosteum leading to bone devascularization, necrosis, and eventually deformity.[9] Rear involvement follows a similar process but uses the longitudinal ligament in the back and often affects the neural arch.[9] Paradiscal, central, and non-bone lesions account for 98 percent of all spinal TB cases, indicating that lesions originating in the back are much more rare.[9]

Cause

Risk factors

Some known risk factors for Pott's Disease include immunodeficiencies (such as those caused by alcohol and drug abuse or HIV), exposure to infected patients, poverty, undernourishment, and lower socioeconomic status. HIV has been identified as one of the primary risk factors for the development of Pott's Disease and this is because HIV compromises the immune system by attacking and destroying crucial immune cells, thereby weakening the body's natural defenses. This impairment significantly reduces the body's ability to combat infections, including tuberculosis , making it more difficult for the body to fight off TB germs effectively.[10] In regions like Sub-Saharan Africa, where the disease is prevalent, HIV often coexists with spinal TB, significantly complicating management and diagnosis.[2][3]

Vitamin D deficiency has also been correlated with an increased risk of Pott's Disease, particularly spinal TB with caseous necrosis, increasing the risk of necrosis compared to individuals with normal vitamin D levels. A deficiency in vitamin D has been associated with the activation of tuberculosis (TB) for a long time. TB patients typically have lower serum vitamin D levels compared to healthy individuals. Extended TB treatment also leads to a reduction in serum vitamin D levels. [11][12]

In developed countries like the United States, Pott's Disease is primarily found in adults. However, in developing countries, data shows that Pott's Disease occurs mainly in young adults and older children.[13] Crowded and poorly ventilated living and working conditions, which are often linked to poverty, significantly increase the risk of tuberculosis transmission.Poverty correlates with limited health knowledge, which in turn results in greater exposure (less educated precaution) to various TB risk factors, including HIV, smoking, and alcohol abuse.[14]

Spread

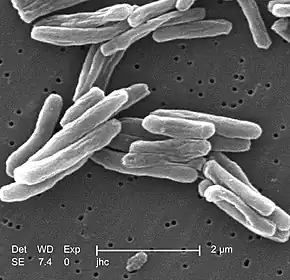

MTB is contracted and spread through aerosol droplets.[9] Respiratory MTB or tuberculosis have been documented in patients that have negative results for specific cultures.[15] The sum of two cases concluded that about 17 percent of transmission occurs from patients who have negative results.[15]

Pathogenesis

Infection of the lungs by the bacteria Mycobacterium tuberculosis eventually spreads through the host's body.[9][4] Without treatment and diagnosis, the infection becomes dormant in the lungs or spreads to other parts of the body through hematogenous dissemination.[9]

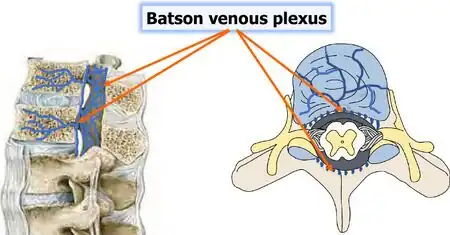

When dissemination occurs, MTB enters the cancellous or spongy bone of the vertebra through the vascular system.[9] It travels specifically from the front and back spinal arteries, and pressures within the torso spreads the infection throughout the vertebral body.[9][8]

It impacts the front of the vertebral body along the subchondral plate.[4] As it advances, progressive destruction occurs leading to vertebral collapse and kyphosis. The spinal canal may become narrowed due to abscesses, granulation tissue, or direct dural invasion resulting in compression of cord and neurological deficits.[4]

Kyphosis is a result of the front of the spine collapsing. Injury to the thoracic spine are more likely to result in kyphosis compared to lumbar spine injuries.[4] A cold abscess can develop if infection spreads to ligaments and soft tissues.[9][4] In the lower back, there is a chance the abscess can move down along the psoas muscle to the upper thigh and eventually break through the skin.[4]

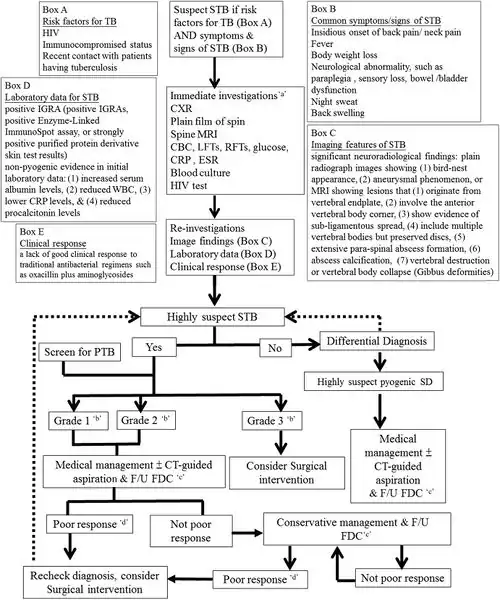

Diagnosis

The most common and earliest clinical symptom of Pott's Disease is back pain, often associated with local tenderness, worsening muscle spasms along the spine, and focal edema. These symptoms can lead to limited and painful movement in all directions of the spine. The second most common clinical symptom is neurological deficits, which can vary depending on the level of the spine affected. [2][4][1]

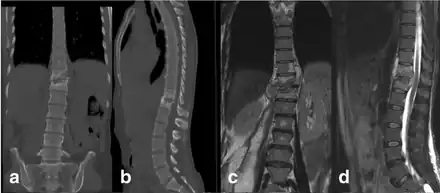

In the early stages of Pott's Disease, imaging techniques such as CT scans, MRIs, or plain radiographs are ordered. For a radiolucent lesion to appear on a plain X-ray, there must be a 30 percent loss of bone mineral, making it difficult to diagnose the early stages of Pott's Disease with a plain radiograph. CT is often used as a guide for biopsy. Overall, it is widely documented that MRI is superior to plain radiographs in diagnosing Pott's Disease. [2][4][1]

Initial suspicion of Pott's Disease is usually based on clinical symptoms and imaging findings, but a definitive diagnosis requires isolating the organism by culture, identifying it, and determining its drug susceptibility. The typical lab procedure for clinical specimens involves an AFB stain. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein are also used as biomarkers for spinal tuberculosis. Other labs include: [2][4][1]

- Radiographs of the spine

- Computed tomography of the spine

Differential

As to the DDx we find that in Spinal tuberculosis it is as follows:[2]

- Atypical bacteria

- Fungi

- Spirochetes

Prevention

As one type of tuberculosis, individuals can not entirely prevent Pott's, but we are able to take steps to reduce the risk of TB infection by avoiding prolonged, close contact with someone who has an active TB infection and getting tested regularly for TB if you're at higher risk or live in a region where TB is common.[19]

Controlling the spread of tuberculosis infection can prevent tuberculous spondylitis and arthritis. Patients who have a positive PPD test may decrease their risk by properly taking medicines to prevent tuberculosis.[3]

Management

When it comes to treatment of Pott's disease, the two main routes that are typically prescribed to patients are drug treatment and surgical intervention.[6] Guidelines from the WHO, CDC, and American Thoracic Society all present chemotherapy to be the first line when it comes to treatment of Pott's disease with surgical interventions being administered as needed for patients who are indicated for it.[6] Antibiotics may also be recommended to help with the eradication of the disease.[6][20] With early intervention, Pott's disease can be cured and completely eradicated from the patient.[19][21] However, there are cases where the tuberculosis is drug-resistant, leading to poorer and possibly life-threatening outcomes in children, the elderly, and immunocompromised patients. Rehabilitation for patients who have just undergone surgery or are recovering from Pott's disease often consist of analgesics for pain management, immobilization of the affected spinal region, and physical therapy for pain-relieving modalities.[22][23]

Medication

The treatment prescribed to patients diagnosed with Pott's disease is similar to treatment that is generally given to patients who have other forms of extrapulmonary tuberculosis.[6] According to guidelines, typical treatment begins with a six to nine month course of chemotherapy.[6][24] The regimen usually consists of an initial 2-month intensive phase of Isoniazid , Rifampin , Pyrazinamide , and Ethambutol .[6] Following the 2-month initial phase, PZA and EMB are discontinued while INH and RIF are continued for the remaining four to seven month continuation phase of the treatment period.[6]

Some practices, however, have recommended treatment regimens of over 12 months given the mortality and disability risks associated with failure to completely eradicate the disease, and the difficulty in assessing the effectiveness of treatment.[24]

Surgery

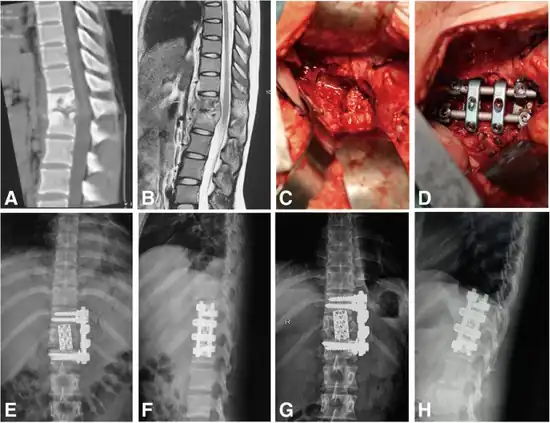

Surgical intervention is required for patients with Pott's disease in the event that there is a need for tissue sampling to clarify diagnoses, resistance to chemotherapy, neurologic deficits , paravertebral abscesses formed from bacterial induced immune response, and kyphotic deformities leading to instability of the spine.[1] However, surgery is up to shared clinical decision making and not an intervention that is defaulted to, as guidelines tend to lead towards less invasive procedures such as chemotherapy and anti-tuberculosis medications.[26]

Typical surgical techniques used are as follows:

- Posterior decompression and fusion with bone autografts[1][27]

- Anterior debridement/decompression and fusion with bone autografts[1][27]

- Anterior debridement/decompression and fusion followed by simultaneous or sequential posterior fusion with instrumentation[1][27]

- Posterior fusion with instrumentation followed by simultaneous or sequential anterior debridement/decompression and fusion[1][27]

Posterior decompression and fusion

In posterior decompression and fusion with bone autografts, the goal is to relieve pressure on the spinal cord and nerves in the lower back and prevent the progression of kyphosis in active disease.[28][29] In this procedure, the lumbar (lower back) vertebrae (L1-L5) are exposed and the intervertebral discs and vertebral material impinging on the spinal cord and/or nerves are removed.[28] The vertebrae (typically L4-L5 due to their load bearing nature and vulnerability to degradation) are then fused together with grafts or instrumentation to help provide more support to the back and spine of the patient.[28]

Kyphosis progression prevention

.jpg)

Surgical intervention is used in patients with kyphosis to primarily prevent the progression of kyphosis in active disease and correct it to a certain extent.[29]

However, surgical intervention is not meant to cure kyphosis in the patient and has variable rates of success in eradicating it in a patient.[29]

In the event that a patient shows signs of kyphosis, the earlier surgical intervention is given, the better the outcome for the patient.[29]

Anterior debridement/decompression and fusion

The goal of the anterior debridement/decompression and fusion with bone autografts procedure is to relieve pressure on the spinal cord and nerves along the anterior side of the spinal cord and help prevent the progression of kyphosis in active disease.[29][30]

The anterior approach is often recommended instead of the posterior approach in cases where only single segments of the vertebrae are affected, and in the event that there is no destruction or collapse of the posterior elements.[30]

In anterior debridement and decompression, tissue damaged by the onset of disease is removed along with vertebral elements and intervertebral discs that are impinging on the spinal cord and/or nerves in the spine.[30]

Vertebrae can then be fused together through the use of grafts or instrumentation to provide more structural support for the spine and back.[30]

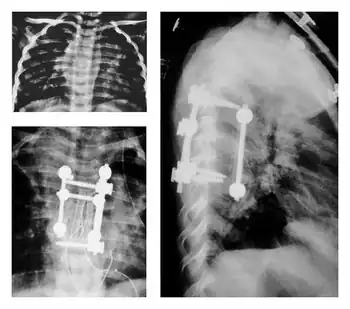

Pediatric surgical interventions

In children with Pott's disease, earlier surgical intervention is often recommended to reduce their increased risk for kyphotic deformity.[1]

This increased risk for deformity is attributed to both the anatomy and biomechanics of children and their developmental stage of life.[1][31]

Due to the proportions of their bodies , limited muscular development, and increased flexibility, gravity can lead to greater deformation and presentation of kyphosis.[31]

After onset of the disease, growth plates in the spine may be destroyed and vertebral bodies suppressed due to kyphosis.[31]

These variable complications would then further deformation, leading to uncontrolled and/or suppressed growth.[31]

Prognosis

The prognosis may include the following, based on prognostic stage:[2]

- Predestructive stage. The duration is < 3 months time

- Early destructive stage. Recovery will be 2 - 4 months time

- Mild angular kyphosis. Two or three vertebrae and kyphosis. Recovery is 3 - 9 months time

- Moderate angular kyphosis. Two to three vertebrae and kyphosis(30 - 60 degrees). Recovery is 6 months to two years time

- Severe angular kyphosis. More than 3 vertebrae and kyphosis(> 60 degrees). Recovery more than 2 years

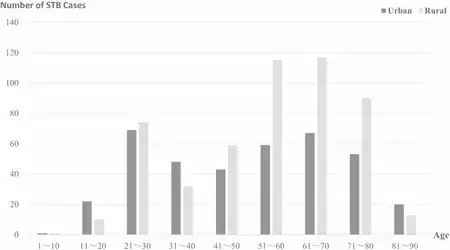

Epidemiology

About 2 percent of all cases of tuberculosis are considered Pott's Disease [33] and about half of the cases of musculoskeletal tuberculosis are Pott's Disease,[9][34] of which 98% affect the anterior column.

The disease can be attributed to 1.3 million deaths per year. There is a correlation between tuberculosis infections and cases of Pott's disease, as it's prevalent in areas where tuberculosis infections are common. Known risk factors like lower socioeconomic status, overcrowding, immunodeficiency, and interactions with people with tuberculosis can influence the rate of diagnosis.[2]

Underdeveloped countries have a higher incidence rate of Pott's disease as it is associated with less ventilated rooms, crowded spaces, poorer hygiene, and less access to healthcare facilities. Increasing food security, reducing poverty, and improving living and working conditions will help to prevent infection and generally enhance the care of those sick. Pott's disease is more common in the working-age population. Still any age group is at risk for developing the disease. Individuals who have use immunosuppressants or have compromised immune systems, chronic diseases , or use tobacco have a significantly increased risk of becoming ill with tuberculosis infections.[35][36]

Multidrug resistant tuberculosis poses a threat to people with Pott's disease, making it difficult to determine infection in people because of the paucibacillary symptoms of the disease. Cases of tuberculosis have been on the decline; however, infections of multidrug resistant tuberculosis have remained constant since the 1990s.[37][38][39]

History

Evidence of tubercular lesions of the vertebral column have been found from the fourth millennium BC in the form of Mesolithic remains in Liguria, Italy. Additionally, tuberculosis spondylitis has been discovered from 3400 BC in the mummified remains of Egyptians. Tuberculosis had affected humans long before it was identified by Sir Percivall Pott.[40]

Important milestones in the development, understanding, and management of tuberculosis spondylitis include the Bacilli Calmette Guerin (BCG) vaccination in 1945, radiological exams, and accessibility of necessary anti tubular medications in the mid 1900's.[7] MRI and CT scans implemented since 1987 for this disease have helped clinicians catch the disease early as well as identify rare complications of the disease, this helps to prevent further worsening of the disease and promote proper management.[41]

Society and culture

Some individuals that may have been affected by Pott's disease are:

- Søren Kierkegaard may have died from Pott disease, according to professor Kaare Weismann and literature scientist Jens Staubrand[42]

- Willem Ten Boom, brother of Corrie Ten Boom, died of tuberculosis of the spine in December 1946.[43]

- Louis Joseph, Dauphin of France, son of King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette[44]

Research

A 2023 study on the evaluation of spinal TB showed that combining T-SPOT with Xpert achieved 95.1 percent sensitivity and 100 percent specificity. Deep learning models like Mask R-CNN now outperform radiologists in CT-based lesion detection, and metagenomic sequencing helps identify coinfections and non-tuberculous pathogens[45]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 Rasouli MR, Mirkoohi M, Vaccaro AR, Yarandi KK, Rahimi-Movaghar V (December 2012). "Spinal tuberculosis: diagnosis and management". Asian Spine Journal. 6 (4): 294–308. doi:10.4184/asj.2012.6.4.294. PMC 3530707. PMID 23275816.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 Viswanathan VK, Subramanian S (2024). "Pott Disease". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 30855915. Archived from the original on 2024-09-17. Retrieved 2024-07-25.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Garg RK, Somvanshi DS (2011). "Spinal tuberculosis: a review". The Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine. 34 (5): 440–454. doi:10.1179/2045772311Y.0000000023. PMC 3184481. PMID 22118251.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 Pott Disease (Tuberculous Spondylitis) at eMedicine

- ↑ Wong-Taylor LA, Scott AJ, Burgess H (May 2013). "Massive TB psoas abscess". BMJ Case Reports. 2013: bcr2013009966. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-009966. PMC 3670072. PMID 23696148.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 Nahid P, Dorman SE, Alipanah N, Barry PM, Brozek JL, Cattamanchi A, Chaisson LH, Chaisson RE, Daley CL, Grzemska M, Higashi JM, Ho CS, Hopewell PC, Keshavjee SA, Lienhardt C, Menzies R, Merrifield C, Narita M, O'Brien R, Peloquin CA, Raftery A, Saukkonen J, Schaaf HS, Sotgiu G, Starke JR, Migliori GB, Vernon A (October 2016). "Official American Thoracic Society/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Infectious Diseases Society of America Clinical Practice Guidelines: Treatment of Drug-Susceptible Tuberculosis". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 63 (7): e147 – e195. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw376. PMC 6590850. PMID 27516382.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Tuli SM (June 2013). "Historical aspects of Pott's disease (spinal tuberculosis) management". European Spine Journal. 22 (Suppl 4): 529–538. doi:10.1007/s00586-012-2388-7. PMC 3691412. PMID 22802129.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Ansari, Sajid; Amanullah, Md. Farid; Rauniyar, RajKumar; Ahmad, Kaleem (2013). "Pott′s spine: Diagnostic imaging modalities and technology advancements". North American Journal of Medical Sciences. 5 (7): 404–411. doi:10.4103/1947-2714.115775. PMC 3759066. PMID 24020048.

- ↑ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 9.10 9.11 9.12 9.13 Glassman I, Nguyen KH, Giess J, Alcantara C, Booth M, Venketaraman V (January 2023). "Pathogenesis, Diagnostic Challenges, and Risk Factors of Pott's Disease". Clinics and Practice. 13 (1): 155–165. doi:10.3390/clinpract13010014. PMC 9955044. PMID 36826156.

- ↑ CDC (2024-06-17). "TB Risk and People with HIV". Tuberculosis (TB). Retrieved 2024-08-01.

- ↑ Talat, Najeeha; Perry, Sharon; Parsonnet, Julie; Dawood, Ghaffar; Hussain, Rabia (May 2010). "Vitamin D Deficiency and Tuberculosis Progression". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 16 (5): 853–855. doi:10.3201/eid1605.091693. PMC 2954005. PMID 20409383.

- ↑ Tabsh, Norah; Bilezikian, John P. (April 2025). "Vitamin D Status as a Risk Factor for Tuberculosis Infection". Advances in Nutrition (Bethesda, Md.). 16 (4): 100394. doi:10.1016/j.advnut.2025.100394. ISSN 2156-5376. PMC 11979928. PMID 39986573.

- ↑ Piña-Garza, J. Eric (2013-01-01), Piña-Garza, J. Eric (ed.), "Chapter 12 - Paraplegia and Quadriplegia", Fenichel's Clinical Pediatric Neurology (Seventh Edition), London: W.B. Saunders, pp. 253–269, doi:10.1016/b978-1-4557-2376-8.00012-8, ISBN 978-1-4557-2376-8, retrieved 2024-08-01

- ↑ "Health Disparities in Tuberculosis". Tuberculosis (TB). 27 February 2025. Archived from the original on 28 August 2025. Retrieved 26 September 2025.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Schirmer, Patricia; Renault, Cybèle A.; Holodniy, Mark (August 2010). "Is spinal tuberculosis contagious?". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 14 (8): e659–666. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2009.11.009. PMID 20181507.

- ↑ Leowattana, Wattana; Leowattana, Pathomthep; Leowattana, Tawithep (18 May 2023). "Tuberculosis of the spine". World Journal of Orthopedics. 14 (5): 275–293. doi:10.5312/wjo.v14.i5.275. ISSN 2218-5836. PMC 10251269. PMID 37304201.

- ↑ Chen, Chang-Hua; Chen, Yu-Min; Lee, Chih-Wei; Chang, Yu-Jun; Cheng, Chun-Yuan; Hung, Jui-Kuo (1 October 2016). "Early diagnosis of spinal tuberculosis". Journal of the Formosan Medical Association. 115 (10): 825–836. doi:10.1016/j.jfma.2016.07.001. ISSN 0929-6646. PMID 27522334. Retrieved 15 September 2025.

- ↑ Tang, Yong; Wu, Wen-jie; Yang, Sen; Wang, Dong-Gui; Zhang, Qiang; Liu, Xun; Hou, Tian-Yong; Luo, Fei; Zhang, Ze-hua; Xu, Jian-zhong (23 July 2019). "Surgical treatment of thoracolumbar spinal tuberculosis—a multicentre, retrospective, case-control study". Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research. 14 (1): 233. doi:10.1186/s13018-019-1252-4. ISSN 1749-799X. PMC 6651955. PMID 31337417.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Pan, Zhimin; Cheng, Zujue; Wang, Jeffrey C.; Zhang, Wei; Dai, Min; Zhang, Bin (September 2021). "Spinal Tuberculosis: Always Understand, Often Prevent, Sometime Cure". Neurospine. 18 (3): 648–650. doi:10.14245/ns.2142788.394. PMC 8497242. PMID 34610698.

- ↑ Rajasekaran S, Soundararajan D, Shetty AP, Kanna RM (December 2018). "Spinal Tuberculosis: Current Concepts". Global Spine Journal. 8 (4_suppl): 96S – 108S. doi:10.1177/2192568218769053. PMC 6295815. PMID 30574444.

- ↑ Patankar A (September 2016). "Tuberculosis of spine: An experience of 30 cases over two years". Asian Journal of Neurosurgery. 11 (3): 226–231. doi:10.4103/1793-5482.145085. PMC 4849291. PMID 27366249.

- ↑ Dhouibi J, Kalai A, Chaabeni A, Aissa A, Ben Salah Frih Z, Jellad A (2024-04-04). "Rehabilitation management of patients with spinal tuberculosis (Review)". Medicine International. 4 (3) 28. doi:10.3892/mi.2024.152. PMC 11040281. PMID 38660125.

- ↑ Jain AK, Jain S (February 2012). "Instrumented stabilization in spinal tuberculosis". International Orthopaedics. 36 (2): 285–292. doi:10.1007/s00264-011-1296-5. PMC 3282857. PMID 21720864.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Lee JY (April 2015). "Diagnosis and treatment of extrapulmonary tuberculosis". Tuberculosis and Respiratory Diseases. 78 (2): 47–55. doi:10.4046/trd.2015.78.2.47. PMC 4388900. PMID 25861336.

- ↑ Yin, Huipeng; Wang, Kun; Gao, Yong; Zhang, Yukun; Liu, Wei; Song, Yu; Li, Shuai; Yang, Shuhua; Shao, Zengwu; Yang, Cao (6 December 2018). "Surgical approach and management outcomes for junction tuberculous spondylitis: a retrospective study of 77 patients". Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research. 13 (1): 312. doi:10.1186/s13018-018-1021-9. ISSN 1749-799X. PMC 6282286. PMID 30522509.

- ↑ Jutte PC, Van Loenhout-Rooyackers JH (January 2006). "Routine surgery in addition to chemotherapy for treating spinal tuberculosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006 (1): CD004532. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004532.pub2. PMC 6532687. PMID 16437489.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 Okada Y, Miyamoto H, Uno K, Sumi M (November 2009). "Clinical and radiological outcome of surgery for pyogenic and tuberculous spondylitis: comparisons of surgical techniques and disease types: Clinical article". Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine. 11 (5): 620–627. doi:10.3171/2009.5.SPINE08331. PMID 19929368.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Jun DS, Yu CH, Ahn BG (September 2011). "Posterior direct decompression and fusion of the lower thoracic and lumbar fractures with neurological deficit". Asian Spine Journal. 5 (3): 146–154. doi:10.4184/asj.2011.5.3.146. PMC 3159062. PMID 21892386.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 Jain AK, Dhammi IK, Jain S, Mishra P (April 2010). "Kyphosis in spinal tuberculosis - Prevention and correction". Indian Journal of Orthopaedics. 44 (2): 127–136. doi:10.4103/0019-5413.61893. PMC 2856387. PMID 20418999.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 Anshori F, Priyamurti H, Rahyussalim AJ (2020). "Anterior debridement and fusion using expandable mesh cage only for the treatment of paraparese due to spondylitis tuberculosis: A case report". International Journal of Surgery Case Reports. 77: 191–197. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2020.10.126. PMC 7652712. PMID 33166818.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 Govender S, Ramnarain A, Danaviah S (July 2007). "Cervical spine tuberculosis in children". Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 460: 78–85. doi:10.1097/BLO.0b013e31806a915f. PMID 17620809.

- ↑ Cao, Manjiang; Jiao, Shuya; Zhang, Quan; Zhu, Bo; Shi, Shiyuan (1 September 2025). "Clinical and epidemiological analysis of 893 patients with spinal tuberculosis: an 11-Year investigation of a general hospital in East China". BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 26 (1): 830. doi:10.1186/s12891-025-09053-5. ISSN 1471-2474.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ↑ Ansari, Sajid; Amanullah, Md. Farid; Rauniyar, RajKumar; Ahmad, Kaleem (2013). "Pott′s spine: Diagnostic imaging modalities and technology advancements". North American Journal of Medical Sciences. 5 (7): 404–411. doi:10.4103/1947-2714.115775. ISSN 1947-2714. PMC 3759066. PMID 24020048. Archived from the original on 2023-02-09. Retrieved 2025-04-28.

- ↑ Manno RL, Yazdany J, Tarrant TK, Kwan M (2022). Current Medical Diagnosis & Treatment 2023. McGraw Hill Education. ISBN 978-1-2646-8734-3.

- ↑ "Tuberculosis (TB)". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 2020-07-30. Retrieved 2024-07-31.

- ↑ Turgut, Mehmet; Turgut, Ahmet T.; Akhaddar, Ali (2017). "Pott's Disease". Tuberculosis of the Central Nervous System: Pathogenesis, Imaging, and Management. Springer International Publishing. pp. 195–209. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-50712-5_15. ISBN 978-3-319-50712-5. Retrieved 26 September 2025.

- ↑ Yadav, Sankalp (8 January 2024). "Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis of the Spine With Bilateral Psoas and Pre- and Paravertebral Abscesses in an Immunocompetent Indian Female With Multiple Adverse Drug Reactions: The World's First Report" (PDF). Cureus. 16 (1): e51835. doi:10.7759/cureus.51835. PMC 10847897. PMID 38327909. Retrieved 25 September 2025.

- ↑ "1.3 Drug-resistant TB". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 6 September 2025. Retrieved 26 September 2025.

- ↑ Lv, Hengliang; Zhang, Xin; Zhang, Xueli; Bai, Junzhu; You, Shumeng; Li, Xuan; Li, Shenlong; Wang, Yong; Zhang, Wenyi; Xu, Yuanyong (22 February 2024). "Global prevalence and burden of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis from 1990 to 2019". BMC Infectious Diseases. 24 (1): 243. doi:10.1186/s12879-024-09079-5. ISSN 1471-2334. PMID 38388352.

- ↑ Khoo, Larry T; Mikawa, Kevin; Fessler, Richard G (March 2003). "A surgical revisitation of Pott distemper of the spine". The Spine Journal. 3 (2): 130–145. doi:10.1016/S1529-9430(02)00410-2. PMID 14589227.

- ↑ Tuli, Surendar M. (June 2013). "Historical aspects of Pott's disease (spinal tuberculosis) management". European Spine Journal. 22 (S4): 529–538. doi:10.1007/s00586-012-2388-7. ISSN 0940-6719. PMC 3691412. PMID 22802129.

- ↑ Krasnik B (2013). "Kierkegaard døde formentlig af Potts sygdom" [Kierkegaard probably died of Pott's disease] (in dansk). Kristeligt Dagblad. Archived from the original on 2016-10-13. Retrieved 2016-10-02.

- ↑ Ten Boom C, Sherrill C, Sherrill J (2015). "Since Then". The Hiding Place. Hendrickson Publishers. ISBN 978-1-61970-597-5.

- ↑ Covington R. "Marie Antoinette". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 2024-01-24. Retrieved 2019-08-18.

- ↑ Li, Zhaoxin; Wang, Jin; Xiu, Xin; Shi, Zhenpeng; Zhang, Qiang; Chen, Deqiang (18 October 2023). "Evaluation of different diagnostic methods for spinal tuberculosis infection". BMC Infectious Diseases. 23 (1): 695. doi:10.1186/s12879-023-08655-5. ISSN 1471-2334. Archived from the original on 24 June 2024. Retrieved 9 October 2025.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)

Further reading

- Jodra, Soraya; Alvarez, Carlos (21 February 2013). "Pott's Disease of the Thoracic Spine". New England Journal of Medicine. 368 (8): 756. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm1207442. PMID 23425168.

- Bydon, Ali; Dasenbrock, Hormuzdiyar H.; Pendleton, Courtney; McGirt, Matthew J.; Gokaslan, Ziya L.; Quinones-Hinojosa, Alfredo (August 2011). "Harvey Cushing, the Spine Surgeon: The Surgical Treatment of Pott Disease". Spine. 36 (17): 1420–1425. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181f2a2c6. PMC 4612634. PMID 21224751.

- Radcliffe, Christopher; Grant, Matthew (9 September 2021). "Pott Disease: A Tale of Two Cases". Pathogens. 10 (9): 1158. doi:10.3390/pathogens10091158. PMC 8465804. PMID 34578190.

- Alajaji, Nouf M.; Sallout, Bahauddin; Baradwan, Saeed (9 May 2022). "A 27-Year-Old Woman Diagnosed with Tuberculous Spondylitis, or Pott Disease, During Pregnancy: A Case Report". American Journal of Case Reports. 23: e936583. doi:10.12659/AJCR.936583. PMC 9195639. PMID 35684941.

External links

| Classification |

|---|