Abdominal tuberculosis

| Abdominal tuberculosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Tuberculosis of abdomen[1] | |

| |

| |

| Specialty | Infectious disease,gastroenterology |

| Symptoms | Abdominal pain, diarrhea, fever, weight loss[3] |

| Complications | Intestinal obstruction, peritonitis[3] |

| Causes | Spread of TB bacteria[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Blood tests,stool tests, endoscopy[3] |

| Treatment | Isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide(surgery is possible)[3][4] |

Abdominal tuberculosis is a type of extrapulmonary tuberculosis which involves the abdominal organs such as intestines, peritoneum and abdominal lymph nodes. It can either occur in isolation or along with a primary focus (such as the lungs) in patients with disseminated tuberculosis.[5] PCR and CT scan(of abdomen) may be used for diagnosis[3]

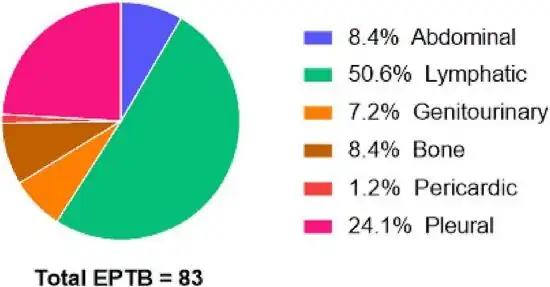

Treatment is with anti-tuberculosis drugs and/or surgery.[3]Higher incidence exists in TB-endemic regions such as South Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, and parts of Latin America.Lack of mandatory organ-specific reporting in EPTB misrepresents true burden estimates[6][7]

Types

- Tubercular lymphadenopathy: Abdominal lymphadenopathy is the most common manifestation of abdominal tuberculosis. The commonly involved lymph nodes are mesenteric nodes and omental nodes. They usually have central areas of caseous necrosis.[4][3]

- Peritoneal tuberculosis: Peritoneal tuberculosis most often presents as abdominal pain and ascites. It can occur most commonly following re-activation of a latent focus of tuberculosis.[3][8]

- Intestinal tuberculosis: Tuberculosis of the intestine can affect multiple areas of the bowel simultaneously. The bacilli penetrate the mucosa, cause caseous necrosis and scarring.[4][3]

- Visceral tuberculosis: This type involves the solid organs in the abdomen, either in isolation or as part of a more widespread infection. Common organs affected include the liver, spleen, and pancreas, as well as the genitourinary system (kidneys, bladder)[3][9][4]

Symptoms and signs

The symptoms of abdominal tuberculosis depends on the sites of involvement, the most common symptoms and signs of abdominal tuberculosis are abdominal pain, ascites. Other clinical features are fever, altered bowel habits, and loss of weight.Night sweats, nausea, loss of appetite, constipation, diarrhoea are some of the rare symptoms of abdominal tuberculosis.[10][3]

Complication

As to complications in the affected individual we find the following may occur:[3]

- Obstruction of gastrointestinal lumen

- Lower gastrointestinal bleeding

- Perforation

- Malnutrition

Risk factors

The risk factors for abdominal tuberculosis are immunocompromised states such as HIV infection, diabetes mellitus and underlying malignancy. Liver cirrhosis and use of peritoneal dialysis are also risk factors for abdominal tuberculosis.[11][3][12]

Pathophysiology

There are several ways by which tuberculosis can infect the abdomen. The tubercle bacteria many enter the abdomen via the consumption of infected milk. Those with existing pulmonary tuberculosis can have abdominal tuberculosis through the ingestion of infected sputum.[4] When the gastrointestinal tract is infected with the bacteria, epitheloid tubercles are formed in the lymphoid tissue of the submucosal layer. Subsequently, caseous necrosis of the tubercles can occur, leading to ulceration of the mucosa. At this stage, the bacili can spread to adjacent lymph nodes and deeper layers of the peritoneum.[4] Tuberculosis can also spread through the blood from the primary focus to elsewhere in the abdomen. Abdominal solid organs, kidneys, lymph nodes and peritoneum can be affected this way.[4] Tuberculosis is also reported to spread to the peritoneum directly from adjacently situated infected foci, such as from the fallopian tubes, adnexa, psoas abscess or secondary tuberculous spondylitis.[4] It can also spread from infected lymph nodes via lymphatic channels.[4]

Diagnosis

The clinical presentation of abdominal tuberculosis is often atypical, tissue samples for confirmation of diagnosis can be difficult to procure and conventional diagnostic methods have poor yield.[5] Therefore, the diagnosis is often delayed.[5] The diagnosis is often suspected clinically with relevant manifestations or epidemiological factors such as known prior tuberculosis and possible TB exposure.[13] A high index of suspicion of TB should be maintained in immunocompromised individuals.[13] Those with extra-abdominal tuberculosis should undergo evaluation for abdominal involvement in case of clinical suspicion. The definitive diagnosis can be established by demonstrating Mycobacterium tuberculosis in peritoneal fluid or in a biopsy specimen. The histopathologic findings of tuberculosis in biopsy, such as caseous granuloma, can be suggestive of tuberculosis, but is not pathognomic.[13] CT scan offers evaluation of involvement of the liver or other organs, as well as for the presence of ascites, lymphadenopathy and peritoneal involvement.[13] Ultrasound scan is useful for demonstrating lymphadenopathy and ascites.[14]

-

![a,b)CT of abdominal tuberculosis[15]](./_assets_/0c70a452f799bfe840676ee341124611/CT_of_abdominal_tuberculosis.jpg) a,b)CT of abdominal tuberculosis[15]

a,b)CT of abdominal tuberculosis[15] -

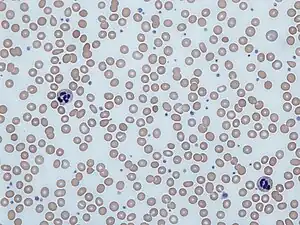

.jpg) Histopathology of tuberculosis of the duodenum. Numerous rod shaped tuberculosis bacilli can be seen.

Histopathology of tuberculosis of the duodenum. Numerous rod shaped tuberculosis bacilli can be seen.

Differential diagnosis

As to the DDx of abdominal tuberculosis we find the following:[3]

- Gastric ulcers

- Hepatic granulomatosis

- Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

Management

Abdominal tuberculosis most often responds to treatment with anti-tuberculosis drugs.[4]

Treatment using anti-tuberculous drugs can cause resolution in fever, ascites and bleeding in a few weeks after the start of the therapy.[13]

Surgical management

Surgery may be warranted in abdominal tuberculosis in case of complications such as perforation, abscess, bleeding, fistula or obstruction.[13]

There are three types of surgeries usually performed in abdominal tuberculosis. The first type of surgery is to bypass the affected segments of the bowel. The second type is a more extensive surgery called hemicolectomy, where a large portion of the bowel is removed.[4]

The third type is stricturoplasty which is done for relieving the luminal obstruction caused due to intestinal tuberculosis.When bowel perforations occur in tuberculosis, it is usually treated by the resection of the involved segments.[4][16]

Prognosis

With treatment, the prognosis is good.Untreated abdominal TB has a mortality rate of 6 to 20 percent and can lead to complications that may require surgical intervention[3]

Epidemiology

Abdominal tuberculosis accounts for up to 5 percent of the tuberculosis cases worldwide.[5][18] It makes up for less than 11–15 percent of all tuberculosis cases in immunocompetent individuals.[5]

Approximately 20 percent of individuals with abdominal tuberculosis have active tuberculosis. The incidence of abdominal tuberculosis has increased in the last few decades due to the increased incidence of HIV infection, which makes individuals vulnerable to tuberculosis.[19][20][21]

History

Ancient history indicates that symptoms resembling abdominal TB were described in Egyptian, and Chinese texts as early as 2000–3500 years ago.[22]

As to recent history Logan and Paustian's postulates in the mid-20th century, helped distinguish abdominal TB from Crohn's disease, which it often mimics[22]

Research

In terms of research we find molecular methods, particularly those targeting Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA, remain the most significant area of progress due to their high specificity and turnaround time.A 2022 review indicates the potential of multiplex Polymerase Chain Reaction, which amplifies multiple DNA targets in a single reaction. This technique has shown a superior sensitivity compared to simple PCR or GeneXpert assays for detecting the low bacterial load often found in abdominal TB tissue samples[23]

References

- ↑ "Abdominal tuberculosis (Concept Id: C0740652) - MedGen - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 4 February 2025. Retrieved 31 August 2025.

- ↑ Ridaura-Sanz, Cecilia; López-Corella, Eduardo; Lopez-Ridaura, Ruy (2012). "Intestinal/Peritoneal Tuberculosis in Children: An Analysis of Autopsy Cases". Tuberculosis Research and Treatment. 2012 (1): 230814. doi:10.1155/2012/230814. ISSN 2090-1518.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 Tobin, Ellis H.; Khatri, Akshay M. (6 February 2025). "Abdominal Tuberculosis". StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 32310575. Retrieved 31 August 2025.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 Debi, Uma (2014). "Abdominal tuberculosis of the gastrointestinal tract: Revisited". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 20 (40): 14831–40. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i40.14831. PMC 4209546. PMID 25356043.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Sharma, SK; Mohan, A (October 2004). "Extrapulmonary tuberculosis". The Indian Journal of Medical Research. 120 (4): 316–53. PMID 15520485.

- ↑ Nath, Preetam (2022). "Epidemiology of Gastrointestinal Tuberculosis". Tuberculosis of the Gastrointestinal system. Springer Nature. pp. 9–19. doi:10.1007/978-981-16-9053-2_2. ISBN 978-981-16-9053-2.

- ↑ Yang, Huafei; Ruan, Xinyi; Li, Wanyue; Xiong, Jun; Zheng, Yuxin (11 November 2024). "Global, regional, and national burden of tuberculosis and attributable risk factors for 204 countries and territories, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Diseases 2021 study". BMC Public Health. 24 (1): 3111. doi:10.1186/s12889-024-20664-w. ISSN 1471-2458. PMC 11552311. PMID 39529028.

- ↑ Wu, David C.; Averbukh, Leon D.; Wu, George Y. (28 June 2019). "Diagnostic and Therapeutic Strategies for Peritoneal Tuberculosis: A Review". Journal of Clinical and Translational Hepatology. 7 (2): 140–148. doi:10.14218/JCTH.2018.00062. ISSN 2225-0719. PMC 6609850. PMID 31293914.

- ↑ Hickey, Andrew J.; Gounder, Lilishia; Moosa, Mahomed-Yunus S.; Drain, Paul K. (6 May 2015). "A systematic review of hepatic tuberculosis with considerations in human immunodeficiency virus co-infection". BMC Infectious Diseases. 15 (1): 209. doi:10.1186/s12879-015-0944-6. ISSN 1471-2334. PMC 4425874. PMID 25943103.

- ↑ Chou, Chia-Huei; Ho, Mao-Wang; Ho, Cheng-Mao; Lin, Po-Chang; Weng, Chin-Yun; Chen, Tsung-Chia; Chi, Chih-Yu; Wang, Jen-Hsian (1 October 2010). "Abdominal Tuberculosis in Adult: 10-Year Experience in a Teaching Hospital in Central Taiwan". Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection. 43 (5): 395–400. doi:10.1016/S1684-1182(10)60062-X. PMID 21075706.

- ↑ "Tuberculosis Risk Factors". Tuberculosis (TB). 5 February 2025. Retrieved 10 September 2025.

- ↑ Chau TN, Leung VK, Wong S, Law ST, Chan WH, Luk IS, Luk WK, Lam SH, Ho YW. Diagnostic challenges of tuberculosis peritonitis in patients with and without end-stage renal failure. Clin Infect Dis. 2007 Dec 15;45(12):e141-6. doi: 10.1086/523727. PMID: 18190308.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 "UpToDate". www.uptodate.com. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 2 January 2021. Archived 10 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Van Hoving, DJ; Griesel, R; Meintjes, G; Takwoingi, Y; Maartens, G; Ochodo, EA (30 September 2019). "Abdominal ultrasound for diagnosing abdominal tuberculosis or disseminated tuberculosis with abdominal involvement in HIV-positive individuals". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (9): CD012777. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012777.pub2. PMC 6766789. PMID 31565799.

- ↑ Subhaschandra Singh, Y. Sobita Devi, Shweta Bhalothia and Veeraraghavan Gunasekaran (2016). "Peritoneal Carcinomatosis: Pictorial Review of Computed Tomography Findings.". International Journal of Advanced Research 4 (7): 735–748. DOI:10.21474/IJAR01/936. ISSN 23205407.

- ↑ "Review on Surgical Management of tuberculous small bowel stricutres" (PDF). Retrieved 2025-09-12.

- ↑ Rolo, M.; González-Blanco, B.; Reyes, C. A.; Rosillo, N.; López-Roa, P. (August 2023). "Epidemiology and factors associated with Extra-pulmonary tuberculosis in a Low-prevalence area". Journal of Clinical Tuberculosis and Other Mycobacterial Diseases. 32 100377. doi:10.1016/j.jctube.2023.100377. ISSN 2405-5794. PMC 10209530. PMID 37252369.

- ↑ Sheer, Todd A.; Coyle, Walter J. (August 2003). "Gastrointestinal tuberculosis". Current Gastroenterology Reports. 5 (4): 273–278. doi:10.1007/s11894-003-0063-1. PMID 12864956. S2CID 22336101.

- ↑ "HIV and Tuberculosis". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 10 June 2025. Retrieved 11 September 2025.

- ↑ Meintjes, Graeme; Maartens, Gary (25 July 2024). "HIV-Associated Tuberculosis". New England Journal of Medicine. 391 (4): 343–355. doi:10.1056/NEJMra2308181. PMID 39047241.

- ↑ Jose, Flores-Almanza; Daniela Naomi, Ortiz-Fernandez; Arturo Amed, Lopez-Marquez; Carolina, Juarez-Hernandez; Victor Salvador, Cabrera-Gallegos; Andres, Armendariz-Rodriguez; Hernandez Alberto, Robles Mendez (2022). "Acute Abdomen in a Patient with HIV, a Challenge for the Surgeon. Systematic Review and Case Report of Intra-Abdominal Tuberculosis". ARC Journal of Surgery. 8 (1): 1–6. doi:10.20431/2455-572X.0801001.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Kumar, Antriksh; Mandavdhare, Harshal S. (2022). "Abdominal Tuberculosis: A Brief History". Tuberculosis of the Gastrointestinal system. Springer Nature. pp. 3–8. doi:10.1007/978-981-16-9053-2_1. ISBN 978-981-16-9053-2.

- ↑ Maulahela, Hasan; Simadibrata, Marcellus; Nelwan, Erni Juwita; Rahadiani, Nur; Renesteen, Editha; Suwarti, S. W. T.; Anggraini, Yunita Windi (1 March 2022). "Recent advances in the diagnosis of intestinal tuberculosis". BMC gastroenterology. 22 (1): 89. doi:10.1186/s12876-022-02171-7. ISSN 1471-230X. Archived from the original on 12 May 2025. Retrieved 28 September 2025.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)