Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare infection

| Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare infection | |

|---|---|

| Other names: MAI infection,[1] Mycobacterium avium complex infection[2] | |

| CT scan of patient with right middle lobe aspiration and Mycobacterium avium infection consistent with Lady Windermere syndrome | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Chronic cough with sputum[3] |

| Complications | Weight loss, enlarged liver, enlarged spleen, enlarged lymph nodes[4] |

| Types | Nodular bronchiectatic (Lady Windermere syndrome); cavitary; disseminated; hypersensitivity pneumonitis[2][3] |

| Causes | Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC)[3] |

| Risk factors | Weak immune system, lung disease[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, sputum culture, medical imaging[5] |

| Differential diagnosis | Tuberculosis, lung cancer, bronchiectasis[3] |

| Treatment | Antibiotics, surgery[5][3] |

| Frequency | 1 in 25,000 (USA)[4] |

Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare infection (MAI) is a type of nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) infection.[4] Multiple areas of the body can be involved, but the lungs are most commonly affected.[4] Symptoms often include a persistent productive cough; though, some may have no symptoms.[3][4] Sputum is generally not bloody nor is fever present.[3] Complications may include weight loss, an enlarged liver, enlarged spleen, or enlarged lymph nodes.[4]

Specifically it is caused by Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC), which includes M. avium and M. intracellulare.[3] These may be either breathed in or swollowed.[4] Risk factors include being immunocompromised and prior lung disease; though, rarely otherwise healthy people may be affected.[3][2] The bacteria is often present in soil, water, and dust.[4] The infection dose not generally spread between people.[3] Diagnosis is based on symptoms, sputum culture, and medical imaging.[5]

Treatment is typically with multiple antibiotics, such as a azithromycin, rifampin, and ethambutol, for a period of at least six months.[5][2] Resistance to multiple antibiotics is common.[5] Surgical removal of the affected lung may also be an option.[3] Death may occur without treatment.[3]

About 1 in 25,000 people are affected in the United States.[4] Older women are more commonly affected.[3] It is most common in the winter and spring.[4] M. avium was first described in 1901 while M. intracellulare was first described in 1949.[2] Farm animals and birds may also be infected.[4]

Signs and symptoms

Lung symptoms are similar to tuberculosis (TB), and include fever, fatigue, weight loss, and coughing up blood. Diarrhea and abdominal pain occur with gastrointestinal involvement.[6][7]

M. avium and M. haemophilum infections in children are distinct, and not associated with abnormalities of the immune system. M. avium typically causes unilateral swelling of one of the lymph nodes of the neck. This node is firm at the beginning, but a 'collar-stud' abscess is formed eventually, which is a characteristic blue-purple in colour with multiple discharging sinuses.[4][8][9]

Cause

MAC bacteria are common in the environment and cause infection when inhaled or swallowed. Recently, M. avium has been found to deposit and grow in bathroom shower heads from which it may be easily aerosolized and inhaled.[10][4]

Bacteria

Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC), also called Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex, is a microbial complex of three Mycobacterium species (i.e. M. avium, M. intracellulare, and M. chimaera).[11] It causes Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare infection.[12][13] Some sources also include Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (MAP).[14]

-

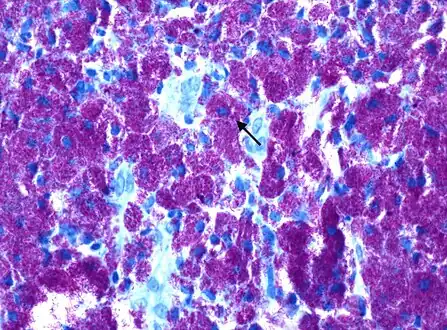

![Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare infection, thin section from a lymph node [15]](./_assets_/0c70a452f799bfe840676ee341124611/Mycobacterium_avium-intracellulare_infection.jpg) Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare infection, thin section from a lymph node [15]

Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare infection, thin section from a lymph node [15] -

Rod-shaped bacilli with Kinyoun AFB stain shown densely packed within histiocytes, consistent with Mycobacterium avium complex

Rod-shaped bacilli with Kinyoun AFB stain shown densely packed within histiocytes, consistent with Mycobacterium avium complex

Risks

MAI is common in immunocompromised individuals, including senior citizens and those with HIV/AIDS or cystic fibrosis. Bronchiectasis, the bronchial condition which causes pathological enlargement of the bronchial tubes, is commonly found with MAI infection. Whether the bronchiectasis leads to the MAC infection or is the result of it is not always known.[16]

Mycobacterium avium complex includes common atypical bacteria, found in the environment which can infect people with HIV and low CD4 cell count; mode of infection is usually inhalation or ingestion.MAC causes disseminated disease in up to 40% of people with HIV in the United States, producing fever, sweats, weight loss, and anemia. Disseminated MAC characteristically affects people with advanced HIV disease and peripheral CD4 cell counts less than 50 cells/uL. Effective prevention and therapy of MAC has the potential to contribute substantially to improved quality of life and duration of survival for HIV-infected persons.[17][18]

MAC in HIV disease is theorized to represent recent acquisition rather than latent infection reactivating . Other risk factors for acquisition of MAC infection include using an indoor swimming pool, consumption of raw or partially cooked fish or shellfish, bronchoscopy and treatment with granulocyte stimulating factor. Disseminated disease was previously the common presentation prior to the advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). Today, in regions where HAART is the standard of care, localized disease presentation is more likely. This generally includes a focal lymphadenopathy/lymphadenitis.[19][20]

Pathophysiology

MAC is the most commonly found form of NTM.[22] Immunodeficiency is not a requirement for MAI.[23]MAC usually affects patients with abnormal lungs or bronchi. However, Jerome Reich and Richard Johnson describe a series of six patients with MAC infection of the right middle lobe or lingula who did not have any predisposing lung disorders.[24][25]The right middle lobe and lingula of the lungs are served by bronchi that are oriented downward when a person is in the upright position. As a result, these areas of the lung may be more dependent upon vigorous voluntary expectoration (cough) for clearance of bacteria and secretions.[26][20] Since the six patients in their retrospective case series were older females, Reich and Johnson proposed that patients without a vigorous cough may develop right middle lobe or left lingular infection with MAC. They proposed this syndrome be named Lady Windermere syndrome, after the character Lady Windermere in Oscar Wilde's play Lady Windermere's Fan. However, little research has confirmed this speculative cause.[27][24]

In terms of the actual mechanism we find that bacteria can enter the respiratory tract, and adhere to and invade mucosal epithelial cells.MAC's ability to survive and replicate within macrophages is a factor in its pathogenesis. In immunocompromised individuals, those with low CD4+ T cell counts, this intracellular replication can proceed unchecked.In immunocompromised individuals, MAC can disseminate from the initial site of infection to other parts of the body, including the lymph nodes, lungs, bone marrow, liver, and spleen, this happens via the lymphatic system and bloodstream.[26][4]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis can be achieved through blood cultures or cultures of other bodily fluids such as sputum. Bone marrow culture can often yield an earlier diagnosis but is usually avoided as an initial diagnostic step because of its invasiveness. Many people will have anemia and neutropenia if the bone marrow is involved. MAC bacteria should always be considered in a person with HIV infection presenting with diarrhea.The diagnosis requires consistent symptoms with two additional signs[28][4]:

- Chest X-ray or CT scan showing evidence of right middle lobe (or left lingular lobe) lung infection

- Sputum culture or bronchoalveolar lavage culture demonstrating the infection is caused by MAC

Disseminated MAC is most readily diagnosed by one positive blood culture. Blood cultures should be performed in patients with symptoms, signs, or laboratory abnormalities compatible with mycobacterium infection. Blood cultures are not routinely recommended for asymptomatic persons, even for those who have CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts less than 100 cells/uL.[17]

Differential diagnosis

As to the DDx we find the following:[29][4]

Prevention

_tablets.jpg)

People with AIDS are given macrolide antibiotics such as azithromycin for prevention.[30] People with HIV infection and less than 50 CD4 cells/uL should be administered prophylaxis against MAC. Prophylaxis should be continued for the patient's lifetime unless multiple drug therapy for MAC becomes necessary because of the development of MAC disease.[17][31]

Clinicians must weigh the potential benefits of MAC prophylaxis against the potential for toxicities and drug interactions, the cost, the potential to produce resistance in a community with a high rate of tuberculosis, and the possibility that the addition of another drug to the medical regimen may adversely affect patients' compliance with treatment. Because of these concerns, therefore, in some situations rifabutin prophylaxis should not be administered.[17]

Before prophylaxis is administered, patients should be assessed to ensure that they do not have the active disease due to MAC, M. tuberculosis, or any other mycobacterial species. This assessment may include a chest radiograph and tuberculin skin test.[17]

Rifabutin, by mouth daily, is recommended for the people's lifetime unless disseminated MAC develops, which would then require multiple drug therapy. Although other drugs, such as azithromycin and clarithromycin, have laboratory and clinical activity against MAC, none has been shown in a prospective, controlled trial to be effective and safe for prophylaxis. Thus, in the absence of data, no other regimen can be recommended at this time. The 300-mg dose of rifabutin has been well tolerated. Adverse effects included neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, rash, and gastrointestinal disturbances.[17]

Treatment

Postinfection treatment involves a combination of antituberculosis antibiotics, including rifampicin, rifabutin, ciprofloxacin, amikacin, ethambutol, streptomycin, clarithromycin or azithromycin.[32]

NTM infections are usually treated with a three-drug regimen of either clarithromycin or azithromycin, plus rifampicin and ethambutol. Treatment typically lasts at least 12 months.[32]

Although studies have not yet identified an optimal regimen or confirmed that any therapeutic regimen produces sustained clinical benefit for patients with disseminated MAC, the Task Force concluded that the available information indicated the need for treatment of disseminated MAC. The Public Health Service, therefore, recommends that regimens be based on the following principles:[17]

- Treatment regimens outside a clinical trial should include at least two agents.

- Every regimen should contain either azithromycin or clarithromycin; many experts prefer ethambutol as a second drug. Many clinicians have added one or more of the following as second, third, or fourth agents: clofazimine, rifabutin, rifampin, ciprofloxacin, and in some situations amikacin. Isoniazid and pyrazinamide are not effective for the therapy of MAC.

- Therapy should continue for the lifetime of the patient if the clinical and microbiologic improvement is observed.

Clinical manifestations of disseminated MAC—such as fever, weight loss, and night sweats—should be monitored several times during the initial weeks of therapy. The microbiologic response, as assessed by blood culture every 4 weeks during initial therapy, can also be helpful in interpreting the efficacy of a therapeutic regimen. Most patients who ultimately respond show substantial clinical improvement in the first 4–6 weeks of therapy. Elimination of the organism from blood cultures may take somewhat longer, often requiring 4–12 weeks.[17]

Children

HIV-infected children less than 12 years of age also develop disseminated MAC. Some age adjustment is necessary when clinicians interpret CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts in children less than 2 years of age. Diagnosis, therapy, and prophylaxis should follow recommendations similar to those for adolescents and adults.[17]

Epidemiology

Infections are more common in individuals with weakened immune systems, such as HIV/AIDS, and chronic lung disease. Rates of disease has increased in recent decades in regions with higher rates of immunocompromised populations.[33][4]

History

The discovery of Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare infection starts in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Initially, the bacteria were identified as distinct from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. By 1933, human cases caused by MAC were documented, and further studies in the 1940s and 1950s clarified the role of Mycobacterium avium and Mycobacterium intracellulare in human infections[34][35]

Society and culture

Literary

The original Chest article proposing the existence and pathophysiology of the Lady Windermere syndrome suggested the character Lady Windermere in Oscar Wilde's Victorian-era play Lady Windermere's Fan is a good example of the fastidious behavior believed to cause the syndrome. The article states: We offer the term, Lady Windermere's Syndrome, from the Victorian-era play, Lady Windermere's Fan, to convey the fastidious behavior hypothesized: "How do you do, Lord Darlington. No, I can't shake hands with you. My hands are all wet with the roses."[36][24]

Shortly after the Lady Windermere syndrome was proposed, a librarian wrote a letter to the editor of Chest challenging the use of Lady Windermere as the eponymous ancestor of the proposed syndrome. In the play, Lady Windermere is a vivacious young woman, married only two years, who never coughs or displays any other signs of illness.[37]

The scholars highlight the literary malapropism, but some in the medical community have adopted the term regardless, and peer-reviewed medical journals still sometimes mention the Lady Windermere syndrome, although it is increasingly viewed as a limiting and sexist term for a serious bacterial infection.[38][39]

Terminology

Lady Windermere syndrome is a term to describe one form of infection in the lungs due to MAC.[24] It is named after a character in Oscar Wilde's 1892 play Lady Windermere's Fan.[40]In recent years, some have described the eponym as inappropriate,[41] and some have noted that it would have been unlikely that Lady Windermere had the condition to which her name was assigned.[42]The more commonly used term is nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) infection, or non-tuberculous mycobacterial infection (NMI). There is no evidence that a person's reluctance to spit has any causal role in NTM infection, the chief reason for the term having been applied to older women presenting with the condition.Lady Windermere syndrome is a type of mycobacterial lung infection.[43]

See also

- Paratuberculosis

References

- ↑ Brettle, R P (1 August 1997). "Mycobacterium avium intracellulare infection in patients with HIV or AIDS". Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 40 (2): 156–160. doi:10.1093/jac/40.2.156. ISSN 0305-7453.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Daley, Charles L. (10 March 2017). "Mycobacterium avium Complex Disease". Microbiology Spectrum. 5 (2): 10.1128/microbiolspec.tnmi7–0045–2017. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.tnmi7-0045-2017. PMC 11687487. PMID 28429679.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 Campos, Arlene. "Pulmonary Mycobacterium avium complex infection". Radiopaedia. Archived from the original on 24 May 2024. Retrieved 14 March 2025. Archived 24 May 2024 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 Akram, SM; Attia, FN (January 2025). "Mycobacterium avium Complex". StatPearls. PMID 28613762.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 "Clinical Overview of Nontuberculous Mycobacteria (NTM)". Nontuberculous Mycobacteria (NTM). 16 May 2024. Archived from the original on 21 February 2025. Retrieved 14 March 2025. Archived 21 February 2025 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Mycobacterium Avium Complex infections | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". Archived from the original on 2022-03-13. Retrieved 2022-09-06. Archived 2022-03-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "NTM Symptoms, Causes & Risk Factors". Archived from the original on 2022-01-22. Retrieved 2022-09-06. Archived 2022-01-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Lindeboom, Jerome A.; Prins, Jan M.; Bruijnesteijn van Coppenraet, Elisabeth S.; Lindeboom, Robert; Kuijper, Ed J. (1 December 2005). "Cervicofacial Lymphadenitis in Children Caused by Mycobacterium haemophilum". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 41 (11): 1569–1575. doi:10.1086/497834. ISSN 1058-4838. Retrieved 22 March 2025.

- ↑ Bruijnesteijn van Coppenraet, Lesla E. S.; Kuijper, Edward J.; Lindeboom, Jerome A.; Prins, Jan M.; Claas, Eric C. J. (January 2005). "Mycobacterium haemophilum and lymphadenitis in children". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 11 (1): 62–68. doi:10.3201/eid1101.040589. ISSN 1080-6040.

- ↑ Feazel, Leah M.; Baumgartner, Laura K.; Peterson, Kristen L.; Frank, Daniel N.; Harris, J. Kirk; Pace, Norman R. (22 September 2009). "Opportunistic pathogens enriched in showerhead biofilms". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (38): 16393–16399. doi:10.1073/pnas.0908446106. Archived from the original on 25 April 2025. Retrieved 17 March 2025.

- ↑ Elsevier, Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary, Elsevier, archived from the original on 2014-01-11, retrieved 2022-09-06. Archived 2014-01-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ White, Lois (2004). Foundations of Nursing. Cengage Learning. p. 1298. ISBN 978-1-4018-2692-5.

- ↑ "Disease Listing, Mycobacterium avium Complex". CDC Bacterial, Mycotic Diseases. Archived from the original on 2010-05-05. Retrieved 2010-11-04. Archived 2010-05-05 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Irving, Peter; Rampton, David; Shanahan, Fergus (2006). Clinical dilemmas in inflammatory bowel disease. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-4051-3377-7.

- ↑ "Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare infection". Wellcome Collection. Retrieved 11 March 2025.

- ↑ Ebihara, Takae; Sasaki, Hidetada (2002). "Bronchiectasis with Mycobacterium avium Complex Infection". New England Journal of Medicine. 346 (18): 1372. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm010899. PMID 11986411.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 17.6 17.7 17.8 U.S. Public Health Service Task Force on Prophylaxis and Therapy for Mycobacterium avium Complex (June 1993). "Recommendations on prophylaxis and therapy for disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex for adults and adolescents infected with human immunodeficiency virus". MMWR Recomm Rep. 42 (RR-9): 14–20. PMID 8393134. Archived from the original on 2017-06-26. Retrieved 2022-09-06. Archived 2017-06-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Havlik JA, Horsburgh CR, Metchock B, Williams PP, Fann SA, Thompson SE (March 1992). "Disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex infection: clinical identification and epidemiologic trends". J. Infect. Dis. 165 (3): 577–80. doi:10.1093/infdis/165.3.577. PMID 1347060.

- ↑ "Disseminated Mycobacterium avium Complex: Adult and Adolescent OIs | NIH". clinicalinfo.hiv.gov. 15 August 2024. Archived from the original on 1 March 2025. Retrieved 16 March 2025.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Griffith, David E.; Aksamit, Timothy; Brown-Elliott, Barbara A.; Catanzaro, Antonino; Daley, Charles; Gordin, Fred; Holland, Steven M.; Horsburgh, Robert; Huitt, Gwen; Iademarco, Michael F.; Iseman, Michael; Olivier, Kenneth; Ruoss, Stephen; von Reyn, C. Fordham; Wallace, Richard J.; Winthrop, Kevin (15 February 2007). "An Official ATS/IDSA Statement: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention of Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Diseases". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 175 (4): 367–416. doi:10.1164/rccm.200604-571ST. ISSN 1073-449X. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

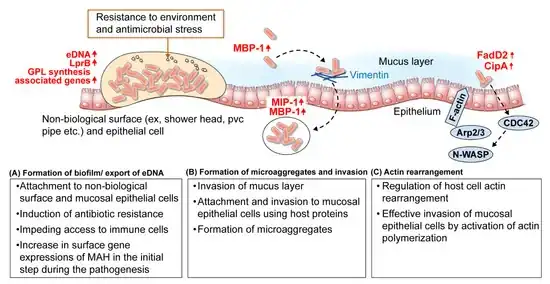

- ↑ Shin, Min-Kyoung; Shin, Sung Jae (16 March 2021). "Genetic Involvement of Mycobacterium avium Complex in the Regulation and Manipulation of Innate Immune Functions of Host Cells". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 22 (6): 3011. doi:10.3390/ijms22063011. ISSN 1422-0067. PMC 8000623. PMID 33809463.

- ↑ Wickremasinghe M, Ozerovitch LJ, Davies G, et al. (December 2005). "Non-tuberculous mycobacteria in patients with bronchiectasis". Thorax. 60 (12): 1045–51. doi:10.1136/thx.2005.046631. PMC 1747265. PMID 16227333.

- ↑ Martins AB, Matos ED, Lemos AC (April 2005). "Infection with the Mycobacterium avium complex in patients without predisposing conditions: a case report and literature review". Braz J Infect Dis. 9 (2): 173–9. doi:10.1590/s1413-86702005000200009. PMID 16127595.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 Reich, J. M.; Johnson, R. E. (June 1992). "Mycobacterium avium complex pulmonary disease presenting as an isolated lingular or middle lobe pattern. The Lady Windermere syndrome". Chest. 101 (6): 1605–1609. doi:10.1378/chest.101.6.1605. ISSN 0012-3692. PMID 1600780.

- ↑ Reich, Jerome M. (August 2018). "In Defense of Lady Windermere Syndrome". Lung. 196 (4): 377–379. doi:10.1007/s00408-018-0122-x. ISSN 0341-2040. PMID 29766262.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 "Mycobacterium Avium Complex (MAC) (Mycobacterium Avium-Intracellulare [MAI]): Background, Pathophysiology, Etiology". eMedicine. 4 April 2025. Retrieved 15 April 2025.

- ↑ "Disease Management Project - Missing Chapter". www.clevelandclinicmeded.com. Archived from the original on 2019-03-06. Retrieved 2019-03-05. Archived 2019-03-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Levin, David L. (1 September 2002). "Radiology of pulmonary Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex". Clinics in Chest Medicine. 23 (3): 603–612. doi:10.1016/S0272-5231(02)00009-6. ISSN 0272-5231. Retrieved 14 March 2025.

- ↑ "Mycobacterium Avium Complex (MAC) (Mycobacterium Avium-Intracellulare [MAI]) Differential Diagnoses". emedicine.medscape.com. Retrieved 15 March 2025.

- ↑ Paul Volberding; Merle A. Sande (2008). Global HIV/AIDS medicine. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 361–. ISBN 978-1-4160-2882-6. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- ↑ "Tables: Drug Therapies to Prevent First Episode of Opportunistic Disease | NIH". clinicalinfo.hiv.gov. 29 October 2024. Archived from the original on 10 March 2025. Retrieved 14 March 2025. Archived 10 March 2025 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 "Mycobacterium Avium Complex (MAC) (Mycobacterium Avium-Intracellulare [MAI]) Treatment & Management: Approach Considerations, Pulmonary MAC Infection in Immunocompetent Patients, Disseminated MAC Infection in Patients with AIDS". 20 July 2021. Archived from the original on 5 July 2022. Retrieved 6 September 2022.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) Archived 5 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine - ↑ "Dermatologic Manifestations of Mycobacterium Avium-Intracellulare Infection: Overview, Epidemiology, Clinical Evaluation". eMedicine. 28 February 2025. Archived from the original on 10 September 2024. Retrieved 12 March 2025.

- ↑ Iseman, Michael D.; Corpe, Raymond F.; O'Brien, Richard J.; Rosenzwieg, David Y.; Wolinsky, Emanuel (1 February 1985). "Disease Due to Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare". Chest. 87 (2): 139S – 149S. doi:10.1378/chest.87.2_Supplement.139S. ISSN 0012-3692. Retrieved 12 March 2025.

- ↑ Bethencourt Mirabal, Arian; Nguyen, Andrew D.; Ferrer, Gustavo (2025). "Lung Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Infections". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Archived from the original on 2024-05-02. Retrieved 2025-03-20. Archived 2024-05-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ M.D, Lisa Sanders (7 June 2013). "Think Like a Doctor: A Cough Solved". Well. Archived from the original on 25 December 2024. Retrieved 15 March 2025.

- ↑ "Chest -- eLetters for Reich and Johnson, 101 (6) 1605-1609". Archived from the original on 2008-06-04. Retrieved 2022-09-06. Archived 2008-06-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Sexton P, Harrison AC (June 2008). "Susceptibility to nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease". Eur. Respir. J. 31 (6): 1322–33. doi:10.1183/09031936.00140007. PMID 18515557.

- ↑ Kasthoori JJ, Liam CK, Wastie ML (February 2008). "Lady Windermere syndrome: an inappropriate eponym for an increasingly important condition". Singapore Med J. 49 (2): e47–9. PMID 18301826.

- ↑ Wilde, Oscar (1940). The Importance of Being Earnest and Other Plays. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-048209-6.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ↑ Kasthoori JJ, Liam CK, Wastie ML (February 2008). "Lady Windermere syndrome: an inappropriate eponym for an increasingly important condition" (PDF). Singapore Med J. 49 (2): e47–9. PMID 18301826. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-11-27. Retrieved 2022-09-06. Archived 2020-11-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Rubin BK (October 2006). "Did Lady Windermere have cystic fibrosis?". Chest. 130 (4): 937–8. doi:10.1378/chest.130.4.937. PMID 17035420.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ Subcommittee Of The Joint Tuberculosis Committee Of The British Thoracic Society (March 2000). "Management of opportunist mycobacterial infections: Joint Tuberculosis Committee Guidelines 1999. Subcommittee of the Joint Tuberculosis Committee of the British Thoracic Society". Thorax. 55 (3): 210–8. doi:10.1136/thorax.55.3.210. PMC 1745689. PMID 10679540.

External links

- Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare Infection at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |