Bolivian hemorrhagic fever

| Bolivian hemorrhagic fever | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Machupo virus infection[1] | |

| |

| |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Fever, malaise, headache and myalgia[3][4] |

| Complications | Multiple organ failure, hypovolemic shock[3][4] |

| Causes | Machupo virus[4] |

| Diagnostic method | Physical exam, recent travel history, PCR[4] |

| Differential diagnosis | Malaria, Dengue,Yellow fever[4] |

| Treatment | Management involves supportive care[5] |

Bolivian hemorrhagic fever (BHF), also known as black typhus or Ordog Fever, is a hemorrhagic fever and zoonotic infectious disease originating in Bolivia after infection by Machupo mammarenavirus.[6]

BHF was first identified in 1963 as an ambisense RNA virus of the Arenaviridae family,[7][8] by a research group led by Karl Johnson. The mortality rate is estimated at 5 to 30 percent. Due to its pathogenicity, Machupo virus requires Biosafety Level Four conditions, the highest level.[9]

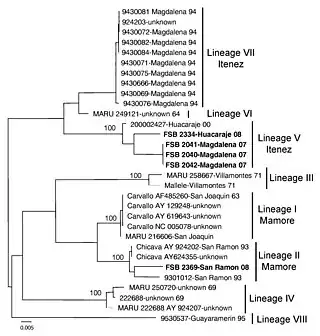

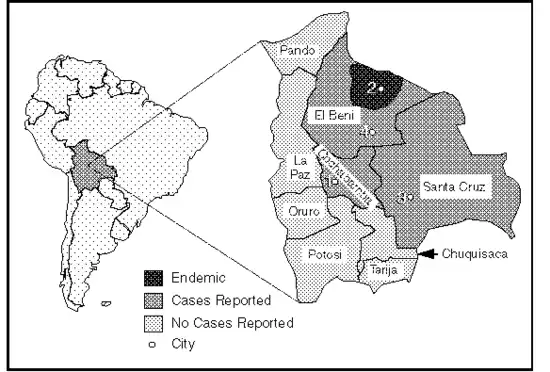

During the period between February and March 2007, some 20 suspected BHF cases (3 fatal) were reported to the Servicio Departamental de Salud (SEDES) in Beni Department, Bolivia. In February 2008, at least 200 suspected new cases (12 fatal) were reported to SEDES.[2] In November 2011, a second case was confirmed near the departmental capital of Trinidad, and a serosurvey was conducted to determine the extent of Machupo virus infections in the department. A SEDES expert involved in the survey expressed his concerns about the expansion of the virus to other provinces outside the endemic regions of Mamoré and Iténez provinces.[10][11]

There is no specific treatment or vaccine available for BHF[5]

Symptoms and signs

The infection of BHF has a slow onset, the affected individual displays:[5]

Severe hemorrhagic or neurologic symptoms are observed in about one third of patients. Neurologic symptoms involve tremors, delirium, and convulsions. The mortality rate is about 25%.[12]

Complications

In terms of the complications of BHF we find, but are not limited to, the following:[4][3]

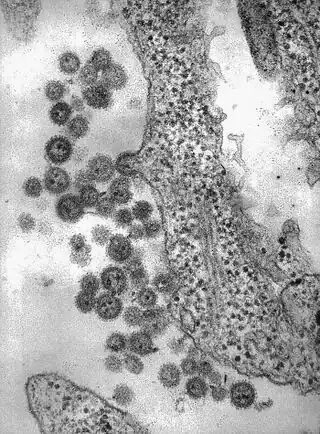

Cause

BHF is due to Machupo virus which belongs to arenavirus family. It is made up of enveloped viruses with two-segmented RNA genomes that are separated into Old World and New World viruses. Most arenaviruses are zoonotic diseases that infect rodent hosts. Human infections is through direct contact with infected materials or the respiratory system. [13]

-

![Mammarenavirus (taxid:1653394) -Machupo mammarenavirus causes Bolivian hemorrhagic fever[14]](./_assets_/ba48700f93e6ccab7a94adacb8f4c793/Arenaviridae_virion_image.svg.png) Mammarenavirus (taxid:1653394) -Machupo mammarenavirus causes Bolivian hemorrhagic fever[14]

Mammarenavirus (taxid:1653394) -Machupo mammarenavirus causes Bolivian hemorrhagic fever[14] -

![Vesper mouse[12]](./_assets_/ba48700f93e6ccab7a94adacb8f4c793/1Medium.jpg) Vesper mouse[12]

Vesper mouse[12]

Vectors

The vector is the large vesper mouse (Calomys callosus), a rodent indigenous to northern Bolivia. Infected animals are asymptomatic and shed the virus in excreta, thereby infecting humans. Evidence of person-to-person transmission of BHF exists but is believed to be rare.[5]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of BHF is based on the following in the affected individual:[4][15]

- Physical exam

- Recent travel history

- PCR

- Virus isolation in cell culture

- Serological tests

Differential diagnosis

The DDx of Bolivian hemorrhagic fever is as follows:[4]

- Argentine hemorrhagic fever

- Malaria

- Dengue

- Yellow fever

- Leptospirosis

Prevention

Measures to reduce contact between the vesper mouse and humans may have contributed to limiting the number of outbreaks, with no cases identified between 1973 and 1994. Although there are no cures or vaccine for the disease, a vaccine developed for the genetically related Junín virus which causes Argentine hemorrhagic fever has shown evidence of cross-reactivity to Machupo virus, and may therefore be an effective prophylactic measure for people at high risk of infection. Post infection (and providing that the person survives the infection), those that have contracted BHF are usually immune to further infection of the disease.[5]

Treatment

There is no specific treatment or vaccine available for BHF. Management primarily involves supportive care in hospital[5][4]

Epidemiology

The epidemiology of Bolivian hemorrhagic fever finds that the disease has caused sporadic outbreaks in rural areas of Bolivia, particularly in the Beni department. The last major outbreak was reported in 2007-2008 with several suspected cases and fatalities[2]

History

.jpg)

In terms of history we find that a team from the Middle American Research Unit led by Dr. Karl Johnson, identified BHF in humans[17]

The disease was first encountered in 1962, in the Bolivian village of San Joaquín, hence the name "Bolivian" Hemorrhagic Fever. When initial investigations failed to find an arthropod carrier, other sources were sought before finally determining that the disease was carried by infected mice. Although mosquitoes were not the cause as originally suspected, the extermination of mosquitoes using DDT to prevent malaria proved to be indirectly responsible for the outbreak in that the accumulation of DDT in various animals along the food chain led to a shortage of cats in the village; subsequently, a mouse plague erupted in the village, leading to an epidemic.[18]

Society and culture

Weaponization

Bolivian hemorrhagic fever was one of three hemorrhagic fevers and one of more than a dozen agents that the United States researched as potential biological weapons before the nation suspended its biological weapons program in 1969.[19] Albert Nickel, a 53-year old animal caretaker at Fort Detrick, died in 1964 from the disease after being bitten by an infected mouse. Nickel Place, on Fort Detrick, is named in his honor. It was also under research by the Soviet Union, under the Biopreparat bureau.[20]

Research

There is some evidence to suggest that the vaccine, which is used to prevent Argentine hemorrhagic fever (caused by the Junín virus), may also offer protection against Bolivian hemorrhagic fever. Investigational vaccines exist for Argentine hemorrhagic fever and RVF; however, neither is approved by FDA or commonly available in the United States.[21][22]The structure of the attachment glycoprotein has been determined by X-ray crystallography and this glycoprotein is likely to be an essential component of any successful vaccine.[23]

References

- ↑ "Bolivian hemorrhagic fever (Concept Id: C0282192) - MedGen - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 4 February 2025. Retrieved 25 January 2025.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Aguilar PV, Carmago W, Vargas J, Guevara C, Roca Y, Felices V, et al. Reemergence of Bolivian hemorrhagic fever, 2007–2008 [letter]. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet] 2009 Sep. Available from http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/15/9/09-0017.htm Archived 2023-04-09 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 2 Dec 2011.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Mangat, Rupinder; Louie, Ted (28 August 2023). Viral Hemorrhagic Fevers. PMID 32809552. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 5 February 2025.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 Silva-Ramos, Carlos Ramiro; Faccini-Martínez, Álvaro A.; Calixto, Omar-Javier; Hidalgo, Marylin (1 March 2021). "Bolivian hemorrhagic fever: A narrative review". Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease. 40: 102001. doi:10.1016/j.tmaid.2021.102001. ISSN 1477-8939. PMID 33640478. Archived from the original on 8 September 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2025.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Kilgore, Paul E.; Peters, Clarence J.; Mills, James N.; Rollin, Pierre E.; Armstrong, Lori; Khan, Ali S.; Ksiazek, Thomas G. (1995). "Prospects for the Control of Bolivian Hemorrhagic Fever - Volume 1, Number 3—July 1995 - Emerging Infectious Diseases journal - CDC". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 1 (3): 97–100. doi:10.3201/eid0103.950308. PMC 2626873. PMID 8903174. Archived from the original on 2024-12-20. Retrieved 2025-01-30.

- ↑ Public Health Agency of Canada: Machupo Virus Pathogen Safety Data Sheet, http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/lab-bio/res/psds-ftss/machupo-eng.php Archived 2017-06-24 at the Wayback Machine, Date Modified: 2011-02-18.

- ↑ "Machupo". Archived from the original on 2008-03-26. Retrieved 2009-01-22.

- ↑ Webb PA, Johnson KM, Mackenzie RB, Kuns ML (July 1967). "Some characteristics of Machupo virus, causative agent of Bolivian hemorrhagic fever". Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 16 (4): 531–8. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.1967.16.531. PMID 4378149.

- ↑ Center for Food Security & Public Health and Institute for International Cooperation in Animal Biologics, Iowa State University: Viral Hemorrhagic Fevers Caused by Arenaviruses, http://www.cfsph.iastate.edu/Factsheets/pdfs/viral_hemorrhagic_fever_arenavirus.pdf Archived 2018-11-23 at the Wayback Machine, last updated: February 23, 2010.

- ↑ "Caso confirmado de fiebre hemorrágica alerta a autoridades benianas," Los Tiempos.com, "Caso confirmado de fiebre hemorrágica alerta a autoridades benianas". Archived from the original on 2012-03-15. Retrieved 2012-11-29., 16/11/2011.

- ↑ "SEDES movilizado para controlar brote de fiebre hemorrágica en Beni; También se Capacita a Los Comunarios y Estudiantes," Lost Tiempos.com, "SEDES movilizado para controlar brote de fiebre hemorrágica en Beni". Archived from the original on 2011-12-01. Retrieved 2012-11-29., 30/11/2011.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Patterson, Michael; Grant, Ashley; Paessler, Slobodan (April 2014). "Epidemiology and pathogenesis of Bolivian hemorrhagic fever". Current Opinion in Virology. 5: 82–90. doi:10.1016/j.coviro.2014.02.007. ISSN 1879-6257. PMC 4028408. PMID 24636947.

- ↑ Basler, Christopher F; Woo, Patrick CY (April 2014). "Editorial overview: Emerging viruses". Current Opinion in Virology. 5: v–vii. doi:10.1016/j.coviro.2014.03.002. PMC 7128464. PMID 24680706.

- ↑ "Mammarenavirus ~ ViralZone". viralzone.expasy.org. Retrieved 26 January 2025.

- ↑ Markin, V. A.; Pantiukhov, V. B.; Markov, V. I.; Bondarev, V. P. (2013). "[Bolivian hemorrhagic fever]". Zhurnal Mikrobiologii, Epidemiologii I Immunobiologii (3): 118–126. ISSN 0372-9311. PMID 24000605. Archived from the original on 2022-04-21. Retrieved 2025-02-05.

- ↑ "International Notes Bolivian Hemorrhagic Fever -- El Beni Department, Bolivia, 1994". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 26 January 2025.

- ↑ "ASTMH - In Memoriam: Karl M. Johnson, MD". www.astmh.org. Archived from the original on 9 May 2025. Retrieved 28 February 2025.

- ↑ Medical Microbiology 2nd edition; Mims et al. Mosby publishing 1998, p 371

- ↑ "Chemical and Biological Weapons: Possession and Programs Past and Present", James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, Middlebury College, April 9, 2002, accessed November 14, 2008.

- ↑ Alibek, Ken and Steven Handelman (1999), Biohazard: The Chilling True Story of the Largest Covert Biological Weapons Program in the World - Told from Inside by the Man Who Ran It, Random House, ISBN 0-385-33496-6.

- ↑ Maiztegui, Julio I.; McKee, Kelly T., Jr; Oro, Julio G. Barrera; Harrison, Lee H.; Gibbs, Paul H.; Feuillade, Maria R.; Enria, Delia A.; Briggiler, Ana M.; Levis, Silvana C.; Ambrosio, Ana M.; Halsey, Neal A.; Peters, Clarence J. (1 February 1998). "Protective Efficacy of a Live Attenuated Vaccine against Argentine Hemorrhagic Fever". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 177 (2): 277–283. doi:10.1086/514211. ISSN 0022-1899. PMID 9466512. Retrieved 5 February 2025.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Shoemaker T, Choi M. "Travelers' Health: Viral Hemorrhagic Fevers". CDC. Archived from the original on 2 February 2022. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- ↑ Bowden, Thomas A.; Crispin, Max; Graham, Stephen C.; Harvey, David J.; Grimes, Jonathan M.; Jones, E. Yvonne; Stuart, David I. (2009-08-15). "Unusual Molecular Architecture of the Machupo Virus Attachment Glycoprotein". Journal of Virology. 83 (16): 8259–8265. doi:10.1128/JVI.00761-09. ISSN 0022-538X. PMC 2715760. PMID 19494008.

Bibliography

- Medical Microbiology 2nd Edition Mims et al. Mosby Publishing 1998 p 371

External links

| Classification |

|---|