Argentine hemorrhagic fever

| Argentine hemorrhagic fever | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Junin hemorrhagic fever[1] | |

| |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Fever, malaise[4] |

| Complications | Petechiae, digestive tract ulcerations, and hematuria[5] |

| Causes | Junin virus[6] |

| Diagnostic method | RT-PCR[7] |

| Differential diagnosis | Bolivian hemorrhagic fever, Lassa fever, Dengue fever[8][9] |

| Prevention | Vaccine Candid #1[10] |

| Treatment | Immune plasma[11][5] |

Argentine hemorrhagic fever (AHF) or O'Higgins disease, is a hemorrhagic fever and zoonotic infectious disease occurring in Argentina. It is caused by the Junín virus[3](an arenavirus, closely related to the Machupo virus, causative agent of Bolivian hemorrhagic fever). Its reservoir of infection is the drylands vesper mouse, a rodent found in Argentina and Paraguay.[3][8]

Ribavirin also has shown a degree of promise in the treatment of arenaviral diseases.[12]The disease was first reported in the town of O'Higgins in Buenos Aires province, Argentina in 1958, giving it one of the names by which it is known.[13]

Signs and symptoms

AHF is a acute disease whose incubation time is within the first couple of weeks, after which the first symptoms appear: fever, headaches, weakness, loss of appetite and will. These intensify less than a week later, forcing the infected to lie down, and producing stronger symptoms such as vascular, renal, hematological and neurological alterations, this stage lasts several weeks.[4][14][5]

Cause

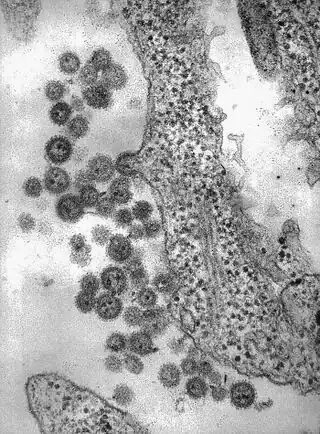

In terms of the etiology we find that Argentine hemorrhagic disease is caused by the Junin virus (JUNV)[6] Junin virus[15] is an arenavirus in the Mammarenavirus genus. Junín virus is a negative sense ssRNA enveloped virion with a variable diameter between 50 and 300 nm. The surface of the particle encompasses a layer of T-shaped glycoproteins, each extending up to 10 nm outwards from the envelope, which are important in mediating attachment and entry into host cells.[16]

-

Schematic structure of an arena virus

Schematic structure of an arena virus -

.jpg) Junin virus

Junin virus

Transmission

.jpg)

The natural reservoir of infection, a small rodent known locally as ratón maicero ("maize mouse"; Calomys musculinus), has chronic asymptomatic infection, and spreads the virus through its saliva and urine. It is found mostly in people who reside or work in rural areas; 80% of those infected are males between 15 and 60 years of age.[17][13]

Mechanism

As to the(simple) mechanism we find that Junín virus replicates in the lungs after inhalation of rodent excreta.Thereafter, spreads to various organs, including the vascular endothelium, myocardium, kidneys, and central nervous system.We find infection can suppress both innate and adaptive immune responses, allowing the virus to spread systemically. Finally, systemic spread leads to tissue damage, excessive cytokine responses, vascular leakage, and disseminated intravascular coagulation.[3][18]

Diagnosis

The evaluation for this hemorrhagic fever in an affected individual can be done via the following:[7]

Differential diagnosis

The DDx of Argentine hemorrhagic fever in an affected individual is as follows:[8][9]

- Bolivian hemorrhagic fever(Machupo virus)

- Venezuelan hemorrhagic fever(Guanarito virus)

- Brazilian hemorrhagic fever(Sabia virus)

- Chikungunya virus

- Leptospirosis

- Malaria

Prevention

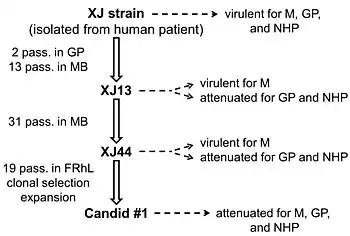

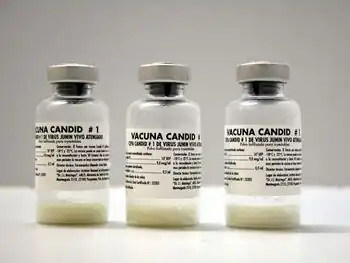

The Candid #1 vaccine for AHF was created in 1985 by Argentine virologist Dr. Julio Barrera Oro. The vaccine was manufactured by the Salk Institute in the United States, and became available in Argentina in 1990. Antibodies produced by Candid #1 vaccination have also demonstrated cross-reactivity with Machupo virus in Rhesus macaques, and thus Candid #1 been considered for prophylactic use against Bolivian hemorrhagic fever.[10]

Candid #1 has been applied to adult high-risk population and is very effective. Between 1991 and 2005 more than 240,000 people were vaccinated, achieving a great decrease in the numbers of reported cases.[20][21][22]

On 29 August 2006 the Maiztegui Institute obtained certification for the production of the vaccine in Argentina. The vaccine produced in Argentina was found to be of similar effectiveness to the US vaccine.[23][22] Details of the vaccine were published in 2011,[20] and a protocol for production of the vaccine was published in 2018.[24]

Demand for the vaccine is insufficient to be commercially appealing due to the small target population, and it is considered an orphan drug; the Argentine government committed itself to manufacture and sponsor Candid #1 vaccine.[20]

Treatment

The specific treatment includes plasma of recovered patients, which, if started early, is extremely effective and reduces mortality .Ribavirin also has shown some promise in treating arenaviral diseases.If untreated, the mortality of AHF reaches 15–30 percent. [11][5]

Epidemiology

Major epidemics often coincide with the harvesting season in Argentina, with peak incidence in May. This is likely due to increased human contact with rodents during agricultural activities and higher rodent populations at this time.The disease is about four times more common in males than females.[3]

-

![Map of South America shows the ranges of mammal species associated with New World mammarenaviruses. The species have been identified as hosts from serosurveillance, or have been confirmed as hosts via virus isolation[25]](./_assets_/ba48700f93e6ccab7a94adacb8f4c793/12866_2024_3257_Fig1_HTML.webp.png) Map of South America shows the ranges of mammal species associated with New World mammarenaviruses. The species have been identified as hosts from serosurveillance, or have been confirmed as hosts via virus isolation[25]

Map of South America shows the ranges of mammal species associated with New World mammarenaviruses. The species have been identified as hosts from serosurveillance, or have been confirmed as hosts via virus isolation[25] -

![VHF- color denotes the number of VHF with at least one outbreak reported by country - Argentine hemorrhagic fever is ArHF[26]](./_assets_/0c70a452f799bfe840676ee341124611/Argentine_hemorrhagic_fever.jpg) VHF- color denotes the number of VHF with at least one outbreak reported by country - Argentine hemorrhagic fever is ArHF[26]

VHF- color denotes the number of VHF with at least one outbreak reported by country - Argentine hemorrhagic fever is ArHF[26] -

.jpg) Geographical location of Argentine hemorrhagic fever

Geographical location of Argentine hemorrhagic fever

History

The disease was first detected in the 1950s in the county of Junín Partido in Buenos Aires, after which its agent, the Junín virus, was named upon its identification in 1958. In the early years, about 1,000 cases per year were recorded, with a high mortality rate . The initial introduction of treatment serums in the 1970s reduced this lethality.[5][27]

The Junin virus was specifically identified and isolated in 1958 by Dr. Adolfo S. Parodi.[28]

Society and culture

Argentine hemorrhagic fever was one of three hemorrhagic fevers and one of more than a dozen agents that the United States researched as potential biological weapons before the nation suspended its biological weapons program.[29] The Soviet Union also conducted research and developing programs on the potential of the hemorragic fever as a biological weapon.[30]

References

- ↑ "Orphanet: Argentine hemorrhagic fever". www.orpha.net. Archived from the original on 13 June 2025. Retrieved 23 February 2025.

- ↑ Ortiz-Prado, Esteban; Vasconez-Gonzalez, Jorge; Becerra-Cardona, D. A.; Farfán-Bajaña, María José; García-Cañarte, Susana; López-Cortés, Andrés; Izquierdo-Condoy, Juan S. (2025). "Hemorrhagic fevers caused by South American Mammarenaviruses: A comprehensive review of epidemiological and environmental factors related to potential emergence". Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease. 64: 102827. doi:10.1016/j.tmaid.2025.102827. ISSN 1873-0442. PMID 40021105.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Grant, Ashley; Seregin, Alexey; Huang, Cheng; Kolokoltsova, Olga; Brasier, Allan; Peters, Clarence; Paessler, Slobodan (19 October 2012). "Junín virus pathogenesis and virus replication". Viruses. 4 (10): 2317–2339. doi:10.3390/v4102317. ISSN 1999-4915. PMC 3497054. PMID 23202466.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Bray, M. (1 January 2009). "Hemorrhagic Fever Viruses". Encyclopedia of Microbiology (Third ed.). Academic Press. pp. 339–353. ISBN 978-0-12-373944-5. Archived from the original on 19 May 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2025.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Enria, Delia A.; Briggiler, Ana M.; Sánchez, Zaida (April 2008). "Treatment of Argentine hemorrhagic fever". Antiviral Research. 78 (1): 132–139. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2007.10.010. ISSN 0166-3542. PMC 7144853. PMID 18054395.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Argentine hemorrhagic fever (Concept Id: C0019097) - MedGen - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2 February 2023. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "South American haemorrhagic fevers - Symptoms, diagnosis and treatment | BMJ Best Practice". bestpractice.bmj.com. Archived from the original on 22 February 2023. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Frank, Maria G.; Beitscher, Adam; Webb, Camille M.; Raabe, Vanessa; Beitscher, Adam; Bhadelia, Nahid; Cieslak, Theodore J.; Davey, Richard T.; Dierberg, Kerry; Evans, Jared D.; Frank, Maria G.; Grein, Jonathan; Kortepeter, Mark G.; Kraft, Colleen S.; Kratochvil, Chris J.; Martins, Karen; McLellan, Susan; Mehta, Aneesh K.; Raabe, Vanessa; Risi, George; Sauer, Lauren; Shenoy, Erica S.; Uyeki, Tim (1 April 2021). "South American Hemorrhagic Fevers: A summary for clinicians". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 105: 505–515. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2021.02.046. ISSN 1201-9712. PMID 33610781. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 16 April 2025.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Mangat, Rupinder; Louie, Ted (2025). "Viral Hemorrhagic Fevers". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 32809552. Archived from the original on 2022-01-11. Retrieved 2025-04-16.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 McLay L, Liang Y, Ly H (January 2014). "Comparative analysis of disease pathogenesis and molecular mechanisms of New World and Old World arenavirus infections". The Journal of General Virology. 95 (Pt 1): 1–15. doi:10.1099/vir.0.057000-0. PMC 4093776. PMID 24068704.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 van Griensven J, De Weiggheleire A, Delamou A, Smith PG, Edwards T, Vandekerckhove P, et al. (January 2016). "The Use of Ebola Convalescent Plasma to Treat Ebola Virus Disease in Resource-Constrained Settings: A Perspective From the Field". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 62 (1): 69–74. doi:10.1093/cid/civ680. PMC 4678103. PMID 26261205.

- ↑ Cherry, James; Kaplan, Sheldon L.; Demmler-Harrison, Gail J.; Steinbach, William; Hotez, Peter J.; Williams, John V. (29 August 2024). Feigin and Cherry's Textbook of Pediatric Infectious Diseases - E-Book: 2-Volume Set. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1915. ISBN 978-0-323-82764-5.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Agnese G (July 2007). "Una rara enfermedad alarma a la modesta población de O'Higgins. Análisis del discurso de la prensa escrita sobre la epidemia de Fiebre Hemorrágica Argentina de 1958" [A rare disease alarms the modest population of O'Higgins. Analysis of the discourse of the written press on the Argentine Hemorrhagic Fever epidemic of 1958] (PDF). Revista de Historia & Humanidades Médicas [Journal of Medical History and Humanities] (in Spanish). 3 (1). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 January 2014.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ "Argentine hemorrhagic fever - National Organization for Rare Disorders". rarediseases.org. Archived from the original on 2025-04-12. Retrieved 2025-04-22.

- ↑ "History of the taxon: Mammarenavirus juninense". Retrieved 23 May 2024.

- ↑ De Martínez Segovia, Z M; De Mitri, M I (February 1977). "Junin virus structural proteins". Journal of Virology. 21 (2): 579–583. doi:10.1128/jvi.21.2.579-583.1977. PMID 189088. Retrieved 20 April 2025.

- ↑ Afrin, Sadia (23 July 2023). "A Narrative Review on Argentine Hemorrhagic Fever: Junin Virus (JUNV)" (PDF). Journal of Clinical Immunology & Microbiology: 1–8. doi:10.46889/JCIM.2023.4202. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 April 2025. Retrieved 22 April 2025.

- ↑ Paessler, Slobodan; Walker, David H. (24 January 2013). "Pathogenesis of the Viral Hemorrhagic Fevers". Annual Review of Pathology: Mechanisms of Disease. 8 (Volume 8, 2013): 411–440. doi:10.1146/annurev-pathol-020712-164041. ISSN 1553-4006. PMID 23121052.

{{cite journal}}:|issue=has extra text (help) - ↑ Berro, Lorena (2 December 2020). "Candid#1, la vacuna huérfana". El Universitario. Retrieved 12 June 2025.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Ambrosio A, Saavedra M, Mariani M, Gamboa G, Maiza A (June 2011). "Argentine hemorrhagic fever vaccines". Human Vaccines. 7 (6): 694–700. doi:10.4161/hv.7.6.15198. PMID 21451263. S2CID 42889001.

- ↑ Ölschläger, Stephan; Flatz, Lukas (11 April 2013). "Vaccination Strategies against Highly Pathogenic Arenaviruses: The Next Steps toward Clinical Trials". PLOS Pathogens. 9 (4): e1003212. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003212. ISSN 1553-7374. PMC 3623805. PMID 23592977.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Enria, Delia A.; Ambrosio, Ana M.; Briggiler, Ana M.; Feuillade, María Rosa; Crivelli, Eleonora (2010). "[Candid#1 vaccine against Argentine hemorrhagic fever produced in Argentina. Immunogenicity and safety]". Medicina. 70 (3): 215–222. ISSN 0025-7680. PMID 20529769.

- ↑ "Presentación — Administración Nacional de Laboratorios e Institutos de Salud - ANLIS". 2 September 2011. Archived from the original on 2 September 2011. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ↑ Ambrosio AM, Mariani MA, Maiza AS, Gamboa GS, Fossa SE, Bottale AJ (2018). "Protocol for the Production of a Vaccine Against Argentinian Hemorrhagic Fever". Hemorrhagic Fever Viruses. Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol. 1604. pp. 305–329. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-6981-4_24. ISBN 978-1-4939-6980-7. PMID 28986845.

- ↑ Lendino, Arianna; Castellanos, Adrian A.; Pigott, David M.; Han, Barbara A. (4 April 2024). "A review of emerging health threats from zoonotic New World mammarenaviruses". BMC Microbiology. 24 (1): 115. doi:10.1186/s12866-024-03257-w. ISSN 1471-2180. PMC 10993514. PMID 38575867.

- ↑ Belhadi, Drifa; El Baied, Majda; Mulier, Guillaume; Malvy, Denis; Mentré, France; Laouénan, Cédric (October 2022). "The number of cases, mortality and treatments of viral hemorrhagic fevers: A systematic review". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 16 (10): e0010889. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0010889. ISSN 1935-2735. PMC 9648854. PMID 36315609.

- ↑ "Arenaviridae*". Fenner's Veterinary Virology (Fifth ed.). Academic Press. 1 January 2017. pp. 425–434. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-800946-8.00023-4. ISBN 978-0-12-800946-8.

- ↑ Enria, D. A.; Oro, J. G. Barrera (2002). "Junin Virus Vaccines". Arenaviruses II: The Molecular Pathogenesis of Arenavirus Infections. Springer. pp. 239–261. ISBN 978-3-642-56055-2. Archived from the original on 2023-09-29. Retrieved 2025-06-28.

- ↑ ""Chemical and Biological Weapons: Possession and Programs Past and Present". James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies. Middlebury College. 9 April 2002. Archived from the original on 2 October 2001. Retrieved 14 November 2008.

- ↑ Wheelis M, Rózsa L, Dando M (2006). Deadly cultures: biological weapons since 1945. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. p. 141. ISBN 0-674-01699-8.

Further reading

- "Argentina fabricará vacuna contra la fiebre hemorrágica" [Argentina will manufacture vaccine against hemorrhagic fever]. Argentine Ministry of Health and Environment (in Spanish). 8 October 2006. Archived from the original on 14 November 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - "La vacuna contra el mal de los rastrojos ya se puede elaborar en el país" [The vaccine against stubble disease can already be made in the country]. Clarín (in Spanish). 29 September 2006. Archived from the original on 10 April 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - "Fiebre Hemorrágica Argentina" [Argentine hemorrhagic fever]. Universidad Blas Pascal (in Spanish). 2001. Archived from the original on 22 October 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Malbrán CG. "Fiebre hemorrágica argentina" [Argentine hemorrhagic fever]. National Administration of Laboratories and Health Institutes (ANLIS) (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 3 October 2006.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 4 October 2006 suggested (help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link)

External links

| Classification |

|---|