Berberine

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

9,10-Dimethoxy-7,8,13,13a-tetradehydro-2′H-[1,3]dioxolo[4′,5′:2,3]berbin-7-ium | |

| Systematic IUPAC name

9,10-Dimethoxy-5,6-dihydro-2H-7λ5-[1,3]dioxolo[4,5-g]isoquinolino[3,2-a]isoquinolin-7-ylium[1] | |

| Other names | |

| Identifiers | |

CAS Number |

|

3D model (JSmol) |

|

Beilstein Reference |

3570374 |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.016.572 |

| EC Number |

|

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

InChI

| |

SMILES

| |

| Properties | |

Chemical formula |

C20H18NO4+ |

| Molar mass | 336.366 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Yellow solid |

| Melting point | 145 °C (293 °F; 418 K)[3] |

Solubility in water |

Slowly soluble[3] |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |

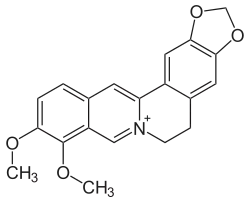

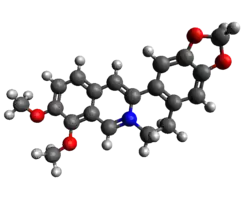

Berberine is an organic compound classified as benzylisoquinoline alkaloid.[4][5] Chemically, it is a quaternary ammonia compound.[4][5]

Its name is derived from the genus of plants, Berberis. Berberine occurs in the roots, bark, stems, and leaves of Berberis vulgaris (barberry), Berberis aristata (tree turmeric), Mahonia aquifolium (Oregon grape) and Hydrastis canadensis (goldenseal).[4]

Due to their yellow pigmentation, raw Berberis materials were once commonly used to dye wool, leather, and wood.[4][6][7] Under ultraviolet light, berberine shows a strong yellow fluorescence.[4][7] As a natural dye, berberine has a color index of 75160.

Plants containing berberine have been used in traditional medicine, and berberine extracts are sold as dietary supplements. Other than in China as an over-the-counter drug, berberine is not approved as a prescription drug, regulated or proven safe in any country.[8]

Biological sources

The following plants are biological sources of berberine:

- Berberis vulgaris (barberry)

- Berberis aristata (tree turmeric)

- Berberis thunbergii

- Fibraurea tinctoria

- Mahonia aquifolium (Oregon grape)

- Hydrastis canadensis (goldenseal)

- Xanthorhiza simplicissima (yellowroot)

- Phellodendron amurense (Amur cork tree)[9]

- Coptis chinensis (Chinese goldthread)

- Tinospora cordifolia

- Argemone mexicana (prickly poppy)

- Eschscholzia californica (California poppy)

Berberine is usually found in the roots, rhizomes, stems, and bark.[4]

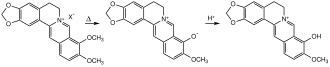

Structure and biosynthesis

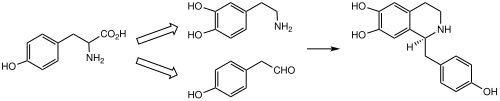

Berberine has a tetracyclic skeleton as is common for alkaloids classified as a benzylisoquinoline alkaloid. The overall skeleton is derived from two equivalents of L-tyrosine. L-Tyrosine is the precursor to L-DOPA and 4-hydroxyphenylacetaldehyde.[10][11]

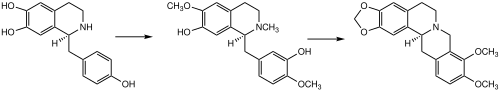

The incorporation of an extra carbon atom as a bridge is distinctive. Formation of the berberine bridge is rationalized as an oxidative process in which the N-methyl group, supplied by S-adenosyl methionine (SAM), is oxidized to an iminium ion, and a cyclization to the aromatic ring occurs by virtue of the phenolic group.[12]

Reticuline is a precursor to some protoberberine alkaloids in plants.[13]

Heating at 190 °C, berberine demethylates giving berberrubine. Alkylation of the resulting zwitterion gives access to many berberine-like derivatives.[14]

Research

Although plants containing berberine are used in traditional medicine, berberine has low bioavailability, indicating limited biological activity in vivo, with no patents issued for its use as a drug.[4][8] Clinical research investigating the use of berberine in humans is limited.[8][15] Although numerous clinical trials have been conducted or are underway, as of 2025, berberine has frequently been withdrawn as a drug candidate, and is not approved as a prescription drug in any country.[8][16]

A 2023 review concluded that berberine may improve lipid concentrations.[16] High-quality, large clinical studies would be required to properly evaluate the effectiveness and safety of berberine in various health conditions.[15]

Supplements, regulation, and safety

Although widely available, dietary supplements have not been approved in the United States for any specific medical use.[8] The quality of berberine supplements can vary across brands: a 2017 study found that out of 15 different products sold, only six contained at least 90% of the specified berberine quantity.[17]

From 2020 to 2022, the US Food and Drug Administration issued warning letters to eight manufacturers of berberine dietary supplements for false advertising and misbranded drug products.[18] In the United States, berberine is not generally recognized as safe (GRAS).[18]

Adverse effects

Longer-term human clinical trials have reported flatulence and diarrhea as common issues.[19]

Drug interactions

Berberine is known to inhibit the activity of CYP3A4, an enzyme important to drug metabolism and clearance of endogenous substances, including steroid hormones such as cortisol, progesterone, and testosterone.[4][8] Several studies have demonstrated that berberine can increase the concentrations of cyclosporine in renal transplant patients and midazolam in healthy adult volunteers, confirming its inhibitory effect on CYP3A4.[20][21][22]

Use in China

It is approved in China as an over-the-counter drug for diarrhea treatment, with the package insert claiming efficacy against E. coli and Shigella spp.[23]

The Chinese package insert contraindicates berberine for people with hemolytic anemia and with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (G6PD deficiency). The insert also specifically precautions its use in children with G6PD deficiency because it can produce hemolytic anemia and jaundice.[23]

References

- ↑ IUPAC Chemical Nomenclature and Structure Representation Division (2013). "P-73.3.1". In Favre HA, Powell WH (eds.). Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry: IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013. IUPAC–RSC. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4.

- 1 2 3 The Merck Index, 14th ed., 1154. Berberine

- 1 2 The Merck Index, 10th Ed. (1983), p.165, Rahway: Merck & Co.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Berberine". The Human Metabolome Database. 7 March 2022. Retrieved 21 August 2025.

- 1 2 "Berberine". PubChem, US National Library of Medicine. 16 August 2025. Retrieved 21 August 2025.

- ↑ Gulrajani ML (2001). "Present status of natural dyes". Indian Journal of Fibre & Textile Research. 26: 191–201. Archived from the original on 20 November 2021. Retrieved 28 December 2017 – via NISCAIR Online Periodicals Repository.

- 1 2 Weiß D (2008). "Fluoreszenzfarbstoffe in der Natur" (in German). Archived from the original on 9 March 2007. Retrieved 17 July 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Berberine". DrugBank. 19 August 2025. Retrieved 21 August 2025.

- ↑ Cicero AF, Baggioni A (2016). "Berberine and Its Role in Chronic Disease". Anti-inflammatory Nutraceuticals and Chronic Diseases. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 928. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 27–45. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-41334-1_2. ISBN 978-3-319-41332-7. ISSN 0065-2598. PMID 27671811.

- ↑ Dewick P (2009). Medicinal Natural Products: A Biosynthetic Approach (3rd ed.). West Sussex, England: Wiley. p. 358. ISBN 978-0-471-49641-0.

- ↑ Tjallinks G, Mattevi A, Fraaije MW (2024). "Biosynthetic Strategies of Berberine Bridge Enzyme-like Flavoprotein Oxidases toward Structural Diversification in Natural Product Biosynthesis". Biochemistry. 63 (17): 2089–2110. doi:10.1021/acs.biochem.4c00320. PMID 39133819.

- ↑ Dewick P (2009). Medicinal Natural Products: A Biosynthetic Approach (3rd ed.). West Sussex, England: Wiley. p. 357. ISBN 978-0-471-49641-0.

- ↑ Park SU, Facchini PJ (June 2000). "Agrobacterium rhizogenes-mediated transformation of opium poppy, Papaver somniferum l., and California poppy, Eschscholzia californica cham., root cultures". Journal of Experimental Botany. 51 (347): 1005–16. doi:10.1093/jexbot/51.347.1005. PMID 10948228.

- ↑ Tillhon M, Guamán Ortiz LM, Lombardi P, et al. (2012). "Berberine: New perspectives for old remedies". Biochemical Pharmacology. 84 (10): 1260–1267. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2012.07.018. PMID 22842630.

- 1 2 Song D, Hao J, Fan D (October 2020). "Biological properties and clinical applications of berberine". Frontiers of Medicine. 14 (5): 564–582. doi:10.1007/s11684-019-0724-6. PMID 32335802. S2CID 216111561.

- 1 2 Hernandez AV, Hwang J, Nasreen I, et al. (2023). "Impact of Berberine or Berberine Combination Products on Lipoprotein, Triglyceride and Biological Safety Marker Concentrations in Patients with Hyperlipidemia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Journal of Dietary Supplements. 21 (2): 242–259. doi:10.1080/19390211.2023.2212762. PMID 37183391. S2CID 258687419.

- ↑ Funk RS, Singh RK, Winefield RD, et al. (May 2018). "Variability in Potency Among Commercial Preparations of Berberine". Journal of Dietary Supplements. 15 (3): 343–351. doi:10.1080/19390211.2017.1347227. PMC 5807210. PMID 28792254.

- 1 2 "Warning letters regarding berberine supplements (search "berberine")". Inspections, Compliance, Enforcement, and Criminal Investigations, US Food and Drug Administration. 19 August 2025. Retrieved 21 August 2025.

- ↑ Yue SJ, Liu J, Wang WX, et al. (August 2019). "Berberine treatment-emergent mild diarrhea associated with gut microbiota dysbiosis". Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 116 109002. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109002. PMID 31154270.

- ↑ Abushammala I (October 2021). "Tacrolimus and herbs interactions: a review". Pharmazie. 76 (10): 468–472. doi:10.1691/ph.2021.1684. PMID 34620272.

- ↑ Hermann R, von Richter O (September 2012). "Clinical evidence of herbal drugs as perpetrators of pharmacokinetic drug interactions". Planta Med. 78 (13): 1458–77. Bibcode:2012PlMed..78.1458H. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1315117. PMID 22855269.

- ↑ Niwa T, Murayama N, Imagawa Y, et al. (May 2015). "Regioselective hydroxylation of steroid hormones by human cytochromes P450". Drug Metab Rev. 47 (2): 89–110. doi:10.3109/03602532.2015.1011658. PMID 25678418.

- 1 2 精华制药集团股份有限公司. "盐酸小檗碱片说明书" [Package Insert: Berberine Hydrochloride Tablets]. ypk.39.net (in Chinese).