Mandelic acid

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Hydroxy(phenyl)acetic acid | |||

| Other names | |||

| Identifiers | |||

CAS Number |

| ||

3D model (JSmol) |

|||

Beilstein Reference |

510011 | ||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| DrugBank | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.001.825 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

Gmelin Reference |

218213 | ||

| KEGG | |||

PubChem CID |

|||

| RTECS number |

| ||

| UNII |

| ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|||

InChI

| |||

SMILES

| |||

| Properties | |||

Chemical formula |

C8H8O3 | ||

| Molar mass | 152.149 g·mol−1 | ||

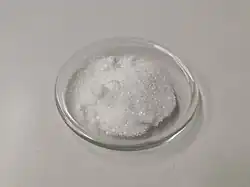

| Appearance | White crystalline powder | ||

| Density | 1.30 g/cm3 | ||

| Melting point | 119 °C (246 °F; 392 K) optically pure: 132 to 135 °C (270 to 275 °F; 405 to 408 K) | ||

| Boiling point | 321.8 °C (611.2 °F; 595.0 K) | ||

Solubility in water |

15.87 g/100 mL | ||

| Solubility | soluble in diethyl ether, ethanol, isopropanol | ||

| Acidity (pKa) | 3.41[3] | ||

Refractive index (nD) |

1.5204 | ||

| Thermochemistry | |||

Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

0.1761 kJ/g | ||

| Pharmacology | |||

| B05CA06 (WHO) J01XX06 (WHO) | |||

| Hazards | |||

| Flash point | 162.6 °C (324.7 °F; 435.8 K) | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Related compounds |

mandelonitrile, phenylacetic acid, vanillylmandelic acid | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |||

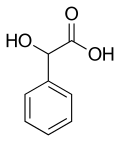

Mandelic acid is an aromatic alpha hydroxy acid (AHA) with the molecular formula C6H5CH(OH)CO2H. It is a white crystalline solid that is soluble in water and polar organic solvents. Its principal use in organic synthesis is as a useful precursor to various drugs.

Properties

At room temperature, mandelic acid is a white or colorless solid with a faint odor.[4] It is highly soluble in diethyl ether[5] but less so in water and ethanol.[2][4][6] It is insoluble in petroleum ether.[5]

The molecule is chiral. The racemic mixture is known as paramandelic acid.

Isolation, synthesis, occurrence

Mandelic acid was discovered in 1831 by the German pharmacist Ferdinand Ludwig Winckler (1801–1868) while heating amygdalin, an extract of bitter almonds, with diluted hydrochloric acid. The name is derived from the German "Mandel" for "almond".[7]

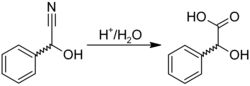

Mandelic acid is usually prepared by the acid-catalysed hydrolysis of mandelonitrile,[8] which is the cyanohydrin of benzaldehyde and can be synthesized in various ways:[9]

Alternatively, it can be prepared by a substitution reaction from bromophenylacetic acid, as well as by hydrolysis routes starting from various α,α-dihaloacetophenones.[10] It also arises by an isomerization reaction upon heating phenylglyoxal with various alkalis.[11][12]

Biosynthesis

Mandelic acid is a substrate or product of several biochemical processes called the mandelate pathway. Mandelate racemase interconverts the two enantiomers via a pathway that involves cleavage of the alpha-CH bond. Mandelate dehydrogenase is yet another enzyme on this pathway.[13] Mandelate also arises from trans-cinnamate via phenylacetic acid, which is hydroxylated.[14] Phenylpyruvic acid is another precursor to mandelic acid.

Derivatives of mandelic acid are formed as a result of metabolism of adrenaline and noradrenaline by monoamine oxidase and catechol-O-methyl transferase. The biotechnological production of 4-hydroxy-mandelic acid and mandelic acid on the basis of glucose was demonstrated with a genetically modified yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, in which the hydroxymandelate synthase naturally occurring in the bacterium Amycolatopsis was incorporated into a wild-type strain of yeast, partially altered by the exchange of a gene sequence and expressed.[15]

It also arises from the biodegradation of styrene[16] and ethylbenzene, as detected in urine.

Uses

Cosmetics

Mandelic acid can be a component of chemical face peels analogous to other alpha hydroxy acids.[2] Mandelic acid is one of the most common chemical components of the "superficial peel" class, which destroy all or part of the epidermis while remaining safe to use on all Fitzpatrick skin types.[17][18][19] The American Academy of Dermatology says there is insufficient evidence to recommend chemical peels (including those with mandelic acid) as a treatment for acne vulgaris.[20] While noting it was widely used in cosmetic products, known to be effective, and frequently prescribed for acne, mandelic acid was among the ingredients not recommended for acne in a 2025 Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology literature review's expert panel, because it is rarely covered by insurance and more costly than treatments with similar effects such as vitamin A derivatives.[21]

Pharmaceuticals

Mandelic acid is widely used for pharmaceuticals as a precursor to various drugs.[22]

The drugs cyclandelate and homatropine[23] are esters of mandelic acid. Homatropine dilates eyes for eye exams and wears off quickly.[23] This effect was discovered by chemist Alfred Ladenburg in 1880 and was preferred because the previous mixture caused blurry vision for days. Mandelic acid replaced tropic acid in the synthesis of homatropine.[23][24][25]

Toxicology

Mandelic acid levels in human urine are a standard biomarker for styrene exposure in industrial hygiene. The unstable metabolite styrene-(7,8)-oxide (styrene oxide) is oxidized into mandelic acid and phenylglyoxylic acid, then exits the body in urine.[26][27] It is also a biomarker for ethylbenzene exposure.[26][28][29] Daily end-of-shift urine collection to monitor styrene exposure is recommended by American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH).[30]

History

Mandelic acid was discovered in 1831 by the German pharmacist Ferdinand Ludwig Winckler (1801–1868) while heating amygdalin, an extract of bitter almonds, with diluted hydrochloric acid. The name is derived from the German "Mandel" for "almond".[7]

The short-acting eye dilation effect as part of homatropine was discovered by chemist Alfred Ladenburg in 1880. Mandelic acid then replaced tropic acid in the synthesis of homatropine.[31][23][24]

Takeru Higuchi and Roy Kuramoto demonstrated one of the earliest forms of pharmaceutical cocrystals in studies published during 1954 that involved mandelic acid.[32]

Safety and handling

Mandelic acid is moderately toxic if ingested.[4][33] It is poisonous if injected.[33] Frequent absorption can result in kidney irritation.[33] When burning, mandelic acid emits acrid smoke and fumes.[33]

Exposing the white crystal form to light will darken to brown and decompose the crystals over time.[4][5][33]

See also

References

- ↑ Merck Index, 11th Edition, 5599.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Ash, Michael (2004). Handbook of Preservatives. Endicott, NY: Synapse Info Resources. p. 444. ISBN 978-1-890595-66-1. Handbook of Preservatives at Google Books.

- ↑ Martell, Arthur E. (1964). "Section II: Organic Ligands, C8H8O3 Mandelic Acid HL". In Sillén, Lars Gunnar; Martell, Arthur E.; Bjerrum, Jannik (eds.). Stability constants of metal-ion complexes. Special Publication (Chemical Society (Great Britain)), number 17 (2nd ed.). London, Great Britain: Chemical Society. p. 568–569. OCLC 208450. Internet Archive stabilityconstan0000jann. Cover title: Stability Constants.

- 1 2 3 4 Hawley's Condensed Chemical Dictionary. Wiley. March 15, 2007. doi:10.1002/9780470114735.hawley10203. ISBN 978-0-471-76865-4. Retrieved September 10, 2025.

- 1 2 3 Ritzer E, Sundermann R (March 11, 2003). "Hydroxycarboxylic Acids, Aromatic; 4.4. Mandelic Acid". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. New York: Wiley. doi:10.1002/14356007.a13_519. ISBN 978-3-527-30385-4. Retrieved September 10, 2025.

- ↑ Harris, Bruce D. (April 15, 2001). "Mandelic Acid". Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis. Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi:10.1002/047084289x.rm017. ISBN 978-0-471-93623-7. Retrieved September 10, 2025.

- 1 2 See:

- Winckler, F. L. (1831) "Ueber die Zersetzung des Calomels durch Bittermandelwasser, und einige Beiträge zur genaueren Kenntniss der chemischen Zusammensetzung des Bittermandelwassers" (On the decomposition of calomel [i.e., mercury(I) chloride] by bitter almond water, and some contributions to a more precise knowledge of the chemical composition of bitter almond water), Repertorium für die Pharmacie, 37 : 388–418; mandelic acid is named on p. 415.

- Winckler, F. L. (1831) "Ueber die chemische Zusammensetzung des Bittermandelwassers; als Fortsetzung der im 37sten Band S. 388 u.s.w. des Repertoriums enthaltenen Mittheilungen" [On the chemical composition of bitter almond water; as a continuation of the report contained in the 37th volume, pp. 388 ff. of the Repertorium], Repertorium für die Pharmacie, 38 : 169–196. On p. 193, Winckler describes the preparation of mandelic acid from bitter almond water and hydrochloric acid (Salzsäure).

- (Editor) (1832) "Ueber einige Bestandtheile der Bittermandeln" (On some components of bitter almonds), Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie, 4 : 242–247.

- Winckler, F. L. (1836) "Ueber die Mandelsäure und einige Salze derselben" (On mandelic acid and some salts of the same), Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie, 18 (3) : 310–319.

- Hermann Schelenz, Geschichte der Pharmazie [The History of Pharmacy] (Berlin, German: Julius Springer, 1904), p. 675.

- ↑ Ritzer, Edwin; Sundermann, Rudolf (2000). "Hydroxycarboxylic Acids, Aromatic". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a13_519. ISBN 3527306730.

- ↑ Corson, B. B.; Dodge, R. A.; Harris, S. A.; Yeaw, J. S. (1926). "Mandelic Acid". Org. Synth. 6: 58. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.006.0058.

- ↑ J. G. Aston; J. D. Newkirk; D. M. Jenkins & Julian Dorsky (1952). "Mandelic Acid". Organic Syntheses; Collected Volumes, vol. 3, p. 538.

- ↑ Pechmann, H. von (1887). "Zur Spaltung der Isonitrosoverbindungen". Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft. 20 (2): 2904–2906. doi:10.1002/cber.188702002156.

- ↑ Pechmann, H. von; Muller, Hermann (1889). "Ueber α-Ketoaldehyde". Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft. 22 (2): 2556–2561. doi:10.1002/cber.188902202145.

- ↑ Kenyon, George L.; Gerlt, John A.; Petsko, Gregory A.; Kozarich, John W. (1995). "Mandelate Racemase: Structure-Function Studies of a Pseudosymmetric Enzyme". Accounts of Chemical Research. 28 (4): 178–186. doi:10.1021/ar00052a003.

- ↑ Lapadatescu, Carmen; Giniès, Christian; Le QuéRé, Jean-Luc; Bonnarme, Pascal (2000). "Novel Scheme for Biosynthesis of Aryl Metabolites from l-Phenylalanine in the Fungus Bjerkandera adusta". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 66 (4): 1517–1522. Bibcode:2000ApEnM..66.1517L. doi:10.1128/AEM.66.4.1517-1522.2000. PMC 92016. PMID 10742235.

- ↑ Mara Reifenrath, Eckhard Boles: Engineering of hydroxymandelate synthases and the aromatic amino acid pathway enables de novo biosynthesis of mandelic and 4-hydroxymandelic acid with Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Metabolic Engineering 45, Januar 2018; S. 246-254. doi:10.1016/j.ymben.2018.01.001.

- ↑ Engström K, Härkönen H, Kalliokoski P, Rantanen J. "Urinary mandelic acid concentration after occupational exposure to styrene and its use as a biological exposure test" Scand. J. Work Environ. Health. 1976, volume 2, pp. 21-6.

- ↑ Chee-Leok Goh, Joyce Teng Ee Lim (February 27, 2023). "Chemical Peels". Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. Wiley. pp. 1–16. doi:10.1002/9781119709268.rook160. ISBN 978-1-119-70921-3. Retrieved September 10, 2025.

- ↑ Lee, Kachiu C.; Wambier, Carlos G.; Soon, Seaver L.; Sterling, J. Barton; Landau, Marina; Rullan, Peter; Brody, Harold J. (2019). "Basic chemical peeling: Superficial and medium-depth peels". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 81 (2). American Academy of Dermatology: 313–324. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.10.079. PMID 30550830. Retrieved September 11, 2025.

Common superficial peels include glycolic acid (GA), salicylic acid (SA), Jessner solution (JS), retinoic acid, lactic acid, mandelic acid, pyruvic acid (PA), and trichloroacetic acid (TCA) 10% to 35%.

- ↑ Quiñonez, Rebecca L.; Agbai, Oma N.; Burgess, Cheryl M.; Taylor, Susan C. (2022). "An update on cosmetic procedures in people of color. Part 2: Neuromodulators, soft tissue augmentation, chemexfoliating agents, and laser hair reduction". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 86 (4). American Academy of Dermatology: 729–739. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.07.080. PMID 35189253. Retrieved September 11, 2025.

The superficial chemexfoliants, 35% to 70% glycolic acid (GA), 20% to 30% salicylic acid (SA), 40% mandelic acid (MA), Jessner solution, 88% lactic acid, phytic acid, and <15% trichloroacetic acid remove the stratum corneum and penetrate to various depth of the epidermis, resulting in an improvement in pigmentation and textural roughness.

- ↑ Reynolds, Rachel V.; Yeung, Howa; Cheng, Carol E.; et al. (May 2024). "Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 90 (5). American Academy of Dermatology: 1006.e1–1006.e30. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.12.017. PMID 38300170. Retrieved September 11, 2025.

- ↑ Alvarez, Gabriella V.; Kang, Bianca Y.; Richmond, Alexandra M.; et al. (April 13, 2025). "Skincare ingredients recommended by cosmetic dermatologists: A Delphi consensus study". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. American Academy of Dermatology. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2025.04.021. PMID 40233838. Retrieved September 11, 2025.

- ↑ Wang, Zerong (September 15, 2010). "Mandelic Acid Synthesis". Comprehensive Organic Name Reactions and Reagents. Wiley. pp. 1816–1819. doi:10.1002/9780470638859.conrr408. ISBN 978-0-471-70450-8. Retrieved September 10, 2025.

- 1 2 3 4 Griffith R, Dukat M (April 26, 2021). "Cholinergics/Anticholinergics". Burger's Medicinal Chemistry and Drug Discovery. Wiley. pp. 1–42. doi:10.1002/0471266949.bmc094.pub3. ISBN 978-0-471-26694-5. Retrieved September 10, 2025.

- 1 2 Rama Sastry, B. V. (January 15, 2003). "Anticholinergic Drugs". Burger's Medicinal Chemistry and Drug Discovery. Wiley. pp. 109–165. doi:10.1002/0471266949.bmc095. ISBN 978-0-471-26694-5. Retrieved September 10, 2025.

- ↑ Patrick, G. L. (September 9, 2005). "History of Drug Discovery". Encyclopedia of Life Sciences (eLS). Wiley. doi:10.1002/9780470015902.a0003090.pub2. ISBN 978-0-470-01617-6. Retrieved September 10, 2025.

- 1 2 Hopf BN, Fustinoni S (February 10, 2021). "Biological Monitoring of Exposure to Industrial Chemicals". Patty's Industrial Hygiene. Wiley. pp. 1–62. doi:10.1002/0471435139.hyg042.pub3. ISBN 978-0-471-29784-0. Retrieved September 10, 2025.

- ↑ Mooney, Aisling; Ward, Patrick G.; O’Connor, Kevin E. (July 6, 2006). "Microbial degradation of styrene: biochemistry, molecular genetics, and perspectives for biotechnological applications". Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 72 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1007/s00253-006-0443-1. ISSN 0175-7598. PMID 16823552. EBSCOhost 21908913. Retrieved September 10, 2025.

- ↑ Boogaard, P. J. (September 15, 2011). "Biomonitoring of the Workplace and Environment". General, Applied and Systems Toxicology. New York: Wiley. doi:10.1002/9780470744307.gat126. ISBN 978-0-470-72327-2. Retrieved September 10, 2025.

- ↑ Kerzic, P. J. (December 27, 2023). "Aromatic Hydrocarbons—Benzene and Other Alkylbenzenes". Patty's Toxicology. Wiley. pp. 1–58. doi:10.1002/0471125474.tox051.pub3. ISBN 978-0-471-31943-6. Retrieved September 10, 2025.

- ↑ Banton M, Rushton EK, Steneholm A (July 3, 2023). "Styrene, Polyphenyls, and Related Compounds. 2.3.6 Biomonitoring/Biomarkers". Patty's Toxicology. Wiley. doi:10.1002/0471125474.tox119.pub2. ISBN 978-0-471-31943-6. Retrieved September 11, 2025.

- ↑ Sneader, WE (August 15, 2007). "Drug Discovery (The History), 1.3 Alkaloid Analogues". Van Nostrand's Scientific Encyclopedia. Wiley. doi:10.1002/9780471743989.vse9887. ISBN 978-0-471-33230-5. Retrieved September 11, 2025.

- ↑ Shan N, Zaworotko MJ (April 26, 2021). "Polymorphic Crystal Forms and Cocrystals in Drug Delivery (Crystal Engineering), 3.2 Case Studies of Pharmaceutical Cocrystals". Burger's Medicinal Chemistry and Drug Discovery. Wiley. doi:10.1002/0471266949.bmc156.pub2. ISBN 978-0-471-26694-5. Retrieved September 11, 2025.

Perhaps, the earliest examples of pharmaceutical cocrystals were described in a series of studies conducted in the 1950s by Higuchi and his coworkers (65, 66), who studied complex formation between macromolecules and certain pharmaceuticals; for example, complexes of polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) with sulfathiazole, procaine hydrochloride, sodium salicylate, benzylphenicillin, chloramphenicol, mandelic acid, caffeine, theophylline, and cortisone were isolated (65, 66).

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Mandelic Acid 90-64-2". Sax's Dangerous Properties of Industrial Materials. New York: Wiley. October 15, 2004. pp. 1–2. doi:10.1002/0471701343.sdp41653. ISBN 978-0-471-47662-7. Retrieved September 10, 2025.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Mandelic Acid". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 559.

-Mandelic_acid_molecule_ball.png)