Relapsing fever

| Relapsing fever | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Tick borne relapsing fever[1],Louse-borne relapsing fever[2] | |

| |

| |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Headache,muscle pain,nausea and vomiting[3] |

| Complications | DIC,gastrointestinal bleed,cerebral bleed,splenic rupture,hyperpyrexia,meningitis[3] |

| Types | Louse-borne relapsing fever, tick-borne relapsing fever[3] |

| Causes | Several species of bacteria in the genus Borrelia[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Blood test[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Brucellosis Ehrlichiosis Anaplasmosis[3] |

| Prevention | Insect repellent, among others[3] |

| Treatment | Doxycycline or penicillin[3] |

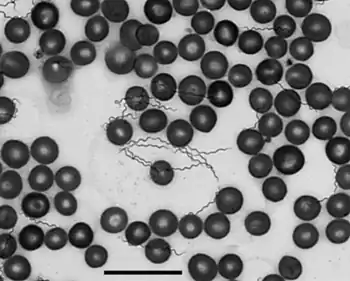

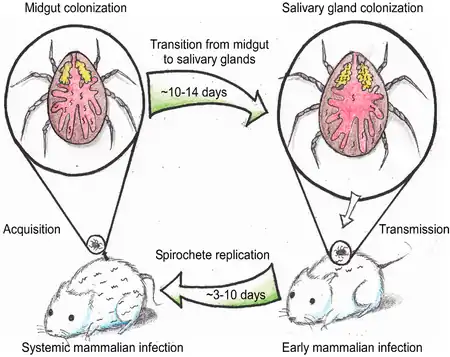

Relapsing fever is a vector-borne disease caused by infection with certain bacteria in the genus Borrelia,[4] which is transmitted through the bites of lice or soft-bodied ticks (genus Ornithodoros).[5]

The primary treatment for relapsing fever is antibiotics, which can be tetracycline, doxycycline, erythromycin, and procaine penicillin G all are commonly used[3][6]

Signs and symptoms

Most people who are infected develop sickness between 5 and 15 days after they are bitten. The symptoms may include a sudden fever, chills, headaches, muscle or joint aches, and nausea. A rash may also occur. These symptoms usually continue for 2 to 9 days, then disappear. This cycle may continue for several weeks if the person is not treated.[7]

Complications

The complications of Relapsing fever are as follows:[3]

- DIC

- Gastrointestinal bleed

- Cerebral bleed

- Splenic rupture

- Focal neurological deficits

- Liver failure

Causes

Louse-borne relapsing fever -Along with Rickettsia prowazekii and Bartonella quintana, Borrelia recurrentis is one of three pathogens of which the body louse (Pediculus humanus humanus) is a vector.[8]

Louse-borne relapsing fever occurs in epidemics amid poor living conditions, famine and war in the developing world. It is currently prevalent in Ethiopia and Sudan.Mortality rate is 1% with treatment and 30–70% without treatment. Poor prognostic signs include severe jaundice, severe change in mental status, severe bleeding and a prolonged QT interval on ECG.Lice that feed on infected humans acquire the Borrelia organisms that then multiply in the gut of the louse. When an infected louse feeds on an uninfected human, the organism gains access when the victim crushes the louse or scratches the area where the louse is feeding. B. recurrentis infects the person via mucous membranes and then invades the bloodstream. No non-human, animal reservoir exists.[1][9][10][11]

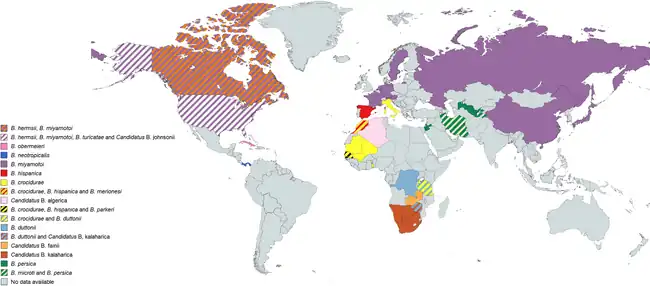

Tick-borne relapsing fever-Tick-borne relapsing fever is found primarily in Africa, Spain, Saudi Arabia, Asia, and certain areas of Canada and the western United States. Other relapsing infections are acquired from other Borrelia species, which can be spread from rodents, and serve as a reservoir for the infection, by a tick vector[13][1][14]:

- Borrelia hispanica

- Borrelia persica

B. hermsii and B. recurrentis cause very similar diseases. However, one or two relapses are common with the disease associated with B. hermsii, which is also the most common cause of relapsing disease in the United States. [13][1][14]

Mechanism

As to the indicator of relapsing fever is the cyclical nature of fever episodes. This is due to Borrelia bacteria capacity to alter their surface proteins, known as variable major proteins.As the hosts immune system develops antibodies against the current VMP, the bacteria switch to expressing different VMP, effectively evading immune clearance.This continuous cycle of antigenic variation and immune response leads to recurring pattern of fever and afebrile periods.[3][15]

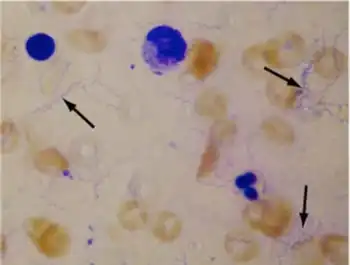

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of relapsing fever can be made on blood smear as evidenced by the presence of spirochetes. Other spirochete illnesses (Lyme disease, syphilis, leptospirosis) do not show spirochetes on blood smear. Although considered the gold standard, this method lacks sensitivity and has been replaced by PCR in many settings.[16]

Differential diagnosis

The DDx of Relapsing fever in the affected individual is as follows:[3]

- Brucellosis

- Ehrlichiosis

- Anaplasmosis

- Plasmodium falciparum(Malaria)

- Trench fever

- Dengue fever

Treatment

Relapsing fever is easily treated with a one- to two-week-course of antibiotics, and most people improve within 24 hours. Complications and death due to relapsing fever are rare.[1][17][3]

Tetracycline-class antibiotics are most effective. These can, however, induce a Jarisch–Herxheimer reaction in over half those treated, producing anxiety, diaphoresis, fever, tachycardia and tachypnea with an initial pressor response followed rapidly by hypotension. Some studies have shown tumor necrosis factor-alpha may be partly responsible for this reaction.[1][17][3]

Epidemiology

In terms of epidemiology we find that Tick-Borne relapsing fever is found worldwide, except in Antarctica, Australia, and Pacific Southwest. In the United States, TBRF is generally confined to the western states, with most cases occurring between May and September[18]

LBRF is rare in the United States but is endemic in northeast Africa -Ethiopia, Sudan, Eritrea,Somalia and has been diagnosed in Europe in refugees from these African countries.[19]

Research

Currently, no vaccine against relapsing fever is available, but research continues. Developing a vaccine is very difficult because the spirochetes avoid the immune response of the infected person (or animal) through antigenic variation. Essentially, the pathogen stays one step ahead of antibodies by changing its surface proteins. These surface proteins, lipoproteins called variable major proteins, have only a moderate percentage of their amino acid sequences in common, which is sufficient to create a new antigenic "identity" for the organism. Antibodies in the blood that are binding to and clearing spirochetes expressing the old proteins do not recognize spirochetes expressing the new ones. Antigenic variation is common among pathogenic organisms.[20][21]

History

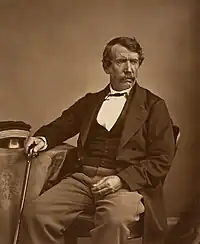

Relapsing fever has been described since the days of the ancient Greeks.[22] After an outbreak in Edinburgh in the 1840s, relapsing fever was given its name, but the etiology of the disease was not better understood for a decade.[22] Physician David Livingstone is credited with the first account in 1857 of a malady associated with the bite of soft ticks in Angola and Mozambique.[23] In 1873, Otto Obermeier first described the disease-causing ability and mechanisms of spirochetes, but was unable to reproduce the disease in inoculated test subjects and thereby unable to fulfill Koch's postulates.[22] The disease was not successfully produced in an inoculated subject until 1874.[22] In 1904 and 1905, a series of papers outlined the cause of relapsing fever and its relationship with ticks.[24][25][26][27] Both Joseph Everett Dutton and John Lancelot Todd contracted relapsing fever by performing autopsies while working in the eastern region of the Congo Free State. Dutton died there on February 27, 1905. The cause of tick-borne relapsing fever across central Africa was named Spirillum duttoni.[28] In 1984, it was renamed Borrelia duttoni.[29] The first time relapsing fever was described in North America was in 1915 in Jefferson County, Colorado.[30]

Sir William MacArthur suggested that relapsing fever was the cause of the yellow plague, variously called pestis flava, pestis ictericia, buidhe chonaill, or cron chonnaill, which struck early Medieval Britain and Ireland, and of epidemics which struck modern Ireland in the famine.[31][32]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Jakab, Ákos; Kahlig, Pascal; Kuenzli, Esther; Neumayr, Andreas (16 February 2022). "Tick borne relapsing fever - a systematic review and analysis of the literature". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 16 (2): e0010212. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0010212. ISSN 1935-2735. PMC 8887751. PMID 35171908.

- ↑ "Orphanet: Relapsing fever". www.orpha.net. Archived from the original on 2025-03-18. Retrieved 2025-03-10.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 Snowden, Jessica (2023). Relapsing fever. NIH-Stat pearl. PMID 28722942. Archived from the original on 16 May 2024. Retrieved 2 March 2025. Archived 16 May 2024 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Schwan T (1996). "Ticks and Borrelia: model systems for investigating pathogen-arthropod interactions". Infect Agents Dis. 5 (3): 167–81. PMID 8805079.

- ↑ Schwan T, Piesman J; Piesman (2002). "Vector interactions and molecular adaptations of Lyme disease and relapsing fever spirochetes associated with transmission by ticks". Emerg Infect Dis. 8 (2): 115–21. doi:10.3201/eid0802.010198. PMC 2732444. PMID 11897061.

- ↑ "Relapsing Fever Treatment & Management: Medical Care, Consultations, Activity". eMedicine. 27 December 2024. Archived from the original on 18 March 2025. Retrieved 10 March 2025.

- ↑ Ryan KJ; Ray CG (editors) (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 432–4. ISBN 978-0-8385-8529-0.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Fournier, Pierre-Edouard (2002). "Human Pathogens in Body and Head Lice". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 8 (12): 1515–8. doi:10.3201/eid0812.020111. PMC 2738510. PMID 12498677. Archived from the original on November 5, 2009. Retrieved October 17, 2010. Archived November 5, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "About Louse-borne Relapsing Fever (LBRF)". Tick and Louse-borne Relapsing Fevers. 31 January 2025. Archived from the original on 21 February 2025. Retrieved 5 March 2025. Archived 21 February 2025 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Relapsing fever: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Archived from the original on 3 March 2025. Retrieved 10 March 2025.

- ↑ Cutler S (2006). "Possibilities for relapsing fever reemergence". Emerg Infect Dis. 12 (3): 369–74. doi:10.3201/eid1203.050899. PMC 3291445. PMID 16704771.

- ↑ Lopez, Job E; Krishnavahjala, Aparna; Garcia, Melissa N; Bermudez, Sergio (15 August 2016). "Tick-Borne Relapsing Fever Spirochetes in the Americas". Veterinary Sciences. 3 (3): 16. doi:10.3390/vetsci3030016. PMC 5606572. PMID 28959690.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "About Soft Tick Relapsing Fever (STRF)". Tick and Louse-borne Relapsing Fevers. 19 July 2024. Archived from the original on 18 February 2025. Retrieved 5 March 2025. Archived 18 February 2025 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "About Hard Tick Relapsing Fever (HTRF)". Tick and Louse-borne Relapsing Fevers. 4 June 2024. Archived from the original on 8 March 2025. Retrieved 5 March 2025.

- ↑ Stone, Brandee L.; Brissette, Catherine A. (2017). "Host Immune Evasion by Lyme and Relapsing Fever Borreliae: Findings to Lead Future Studies for Borrelia miyamotoi". Frontiers in Immunology. 8: 12. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2017.00012. ISSN 1664-3224. Archived from the original on 2025-02-03. Retrieved 2025-04-10.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) Archived 2025-02-03 at the Wayback Machine - ↑ Fotso Fotso A, Drancourt M (2015). "Laboratory Diagnosis of Tick-Borne African Relapsing Fevers: Latest Developments". Frontiers in Public Health. 3: 254. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2015.00254. PMC 4641162. PMID 26618151.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Kahlig, Pascal; Paris, Daniel H.; Neumayr, Andreas (11 March 2021). "Louse-borne relapsing fever—A systematic review and analysis of the literature: Part 1—Epidemiology and diagnostic aspects". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 15 (3): e0008564. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0008564. ISSN 1935-2735. PMC 7951878. PMID 33705384.

- ↑ "Relapsing Fever: Background, Pathophysiology, Epidemiology". eMedicine. 27 December 2024. Archived from the original on 27 August 2024. Retrieved 2 March 2025. Archived 27 August 2024 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Relapsing Fever - Infectious Diseases". MSD Manual Professional Edition. Archived from the original on 18 March 2025. Retrieved 2 March 2025.

- ↑ Krajacich, Benjamin J.; Lopez, Job E.; Raffel, Sandra J.; Schwan, Tom G. (21 October 2015). "Vaccination with the variable tick protein of the relapsing fever spirochete Borrelia hermsii protects mice from infection by tick-bite". Parasites & Vectors. 8 (1): 546. doi:10.1186/s13071-015-1170-1. ISSN 1756-3305. PMID 26490040.

- ↑ Cutler, Sally J. (1 December 2015). "Relapsing Fever Borreliae: A Global Review". Clinics in Laboratory Medicine. 35 (4): 847–865. doi:10.1016/j.cll.2015.07.001. ISSN 0272-2712. PMID 26593261. Archived from the original on 18 March 2025. Retrieved 13 March 2025.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 Cutler, S.J. (April 2010). "Relapsing fever – a forgotten disease revealed". Journal of Applied Microbiology. 108 (4): 1115–1122. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04598.x. ISSN 1365-2672. PMID 19886891. S2CID 205322810.

- ↑ Livingstone D (1857) Missionary travels and researches in South Africa. London: John Murray

- ↑ Cook AR (1904). "Relapsing fever in Uganda". J Trop Med Hyg. 7: 24–26.

- ↑ Ross, P. H.; Milne, A. D. (1904). "Tick Fever". British Medical Journal. 2 (2291): 1453–4. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.2291.1453. PMC 2355890. PMID 20761784.

- ↑ Dutton JE, Todd JL (1905). "The nature of human tick-fever in the eastern part of the Congo Free State with notes on the distribution and bionomics of the tick". Liverpool School Trop Med Mem. 17: 1–18.

- ↑ Wellman FC (1905). "Case of relapsing fever, with remarks on its occurrence in the tropics and its relation to "tick fever"". J Trop Med. 8: 97–99.

- ↑ Novy, F. G.; Knapp, R. E. (1906). "Studies on Spirillum obermeieri and related organisms". Journal of Infectious Diseases. 3 (3): 291–393. doi:10.1093/infdis/3.3.291. hdl:2027/hvd.32044106407547. JSTOR 30071844.

- ↑ Kelly RT (1984) "Genus IV. Borrelia Swellengrebel 1907" in Krieg NR (ed.) Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins

- ↑ Davis, Gordon E. (1940-01-01). "Ticks and Relapsing Fever in the United States". Public Health Reports. 55 (51): 2347–2351. doi:10.2307/4583554. JSTOR 4583554.

- ↑ Bonser, Wilfrid; MacArthur, Wm (1944). "Epidemics during the Anglo-Saxon period, with appendix: Famine fevers in England and Ireland". Journal of the British Archaeological Association. 9: 48–71. doi:10.1080/00681288.1944.11894687.

- ↑ MacArthur, W (1947). "Famine fevers in England and Ireland". Postgraduate Medical Journal. 23 (260): 283–6. doi:10.1136/pgmj.23.260.283. PMC 2529527. PMID 20248471.

External links

- CDC: Relapsing Fever Archived 2022-07-16 at the Wayback Machine