Ancylostomiasis

| Ancylostomiasis | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Ancylostoma duodenale infection[1] | |

| |

| |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Diarrhea, abdominal pain, and nausea[3] |

| Causes | Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator americanus [3] |

| Diagnostic method | Stool sample[3] |

| Differential diagnosis | Intestinal malignancy,intestinal polyps,other STH infection[3] |

| Prevention | Improved hygiene/sanitation[3] |

| Treatment | Albendazole, mebendazole[3] |

Ancylostomiasis is a hookworm disease caused by infection with Ancylostoma hookworms. The name is derived from Greek ancylos αγκύλος "crooked, bent" and stoma στόμα "mouth".[4][3][5]

Helminthiasis may also refer to ancylostomiasis, but this term also refers to all other parasitic worm diseases as well. In the United Kingdom, if acquired in the context of working in a mine, the condition is eligible for Industrial Injuries Disability Benefit. It is a prescribed disease (B4) under the relevant legislation.§[6]

Ancylostomiasis is caused when hookworms, present in large numbers, produce an iron deficiency anemia by sucking blood from the host's intestinal walls.[3][7]Treatment of hookworm disease is mebendazole[3]

Signs and symptoms

Depending on the organism, the signs and symptoms vary. Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator americanus can enter the blood stream. [3]

In Ancylostoma braziliensis as the larvae are in an abnormal host, they do not mature to adults but instead migrate through the skin until killed by the host's inflammatory response. This migration causes local intense itching and a red serpiginous lesion.[8] In general the symptoms are the following:[9]

Complications

As to the complication in affected individuals we find the following:[3]

- Iron deficient anemia

- Nutritional deficiency

- Growth impairment in children

Causes

In terms of the etiology we find that Ancylostomiasis is caused by parasitic nematodes of the genus Ancylostoma and Necator. The primary species responsible for human infection are Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator americanus[9]

Mechanism

The infection is usually contracted by people walking barefoot over contaminated soil. In penetrating the skin, the larvae may cause an allergic reaction. It is due to the itchy patch at the site of entry that the early infection gets its nickname "ground itch". Once larvae have broken through the skin,they enter the bloodstream and are carried to the lungs . The larvae migrate from the lungs up the windpipe to be swallowed and carried back down to the intestine. If humans come into contact with larvae of the dog hookworm or the cat hookworm, or of certain other hookworms that do not infect humans, the larvae may penetrate the skin. Sometimes, the larvae are unable to complete their migratory cycle in humans. Instead, the larvae migrate just below the skin producing snake-like markings. This is referred to as a creeping eruption or cutaneous larva migrans.[3][10][11]

Diagnosis

In terms of the diagnosis of Ancylostomiasis the following is done via:[9][12]

- Complete blood count(anemia)

- Stool test

- Endoscopy

Differential diagnosis

As to the DDx in Ancylostomiasis in the affected individual the following should be considered:[3]

- Intestinal malignancy

- Intestinal polyps

- Hemolytic anemia

- Other STH infection

- Migratory myiasis

- Scabies infection

Prevention

Control of this parasite should be directed against reducing the level of environmental contamination. Treatment of heavily infected individuals is one way to reduce the source of contamination . Other obvious methods are to improve access to sanitation, e.g. toilets, convincing people to maintaining them in a clean, functional state.[3][13]

Treatment

The drug of choice for the treatment of hookworm disease is mebendazole which is effective against both species, and in addition, will remove the intestinal worm Ascaris also, if present. The drug is very efficient, requiring only a single dose and is inexpensive. However, treatment requires more than giving the anthelmintic, the patient should also receive dietary supplements to improve their general level of health, in particular iron supplementation is very important. Iron is an important constituent of a multitude of enzyme systems involved in energy metabolism, DNA synthesis and drug detoxification.[3][14]

An infection of N. americanus parasites can be treated by using benzimidazoles, albendazole, and mebendazole. A blood transfusion may be necessary in severe cases of anemia. Light infections are usually left untreated in areas where reinfection is common. Iron supplements and a diet high in protein will speed the recovery process. In a study involving 60 males with Trichuris trichiura and/or N. americanus infections, both albendazole and mebendazole were highly effective in curing T. trichiura. However, albendazole had a high percentage cure rate for N. americanus, while mebendazole only had a low percentage cure rate. This suggests albendazole is most effective for treating both T. trichiura and N. americanus.[14][15][16]

Epidemiology

Hookworm anaemia was first described by Wilhelm Griesenger in Egypt, Cairo in 1852. He found thousands of adult ancylostomes in the small bowel of a 20-year old soldier who was suffering from severe diarrhoea and anaemia (labelled at the time as Egyptian chlorosis).[17] The subject was revisited in Europe when there was an outbreak of "miner's anaemia" in Italy.[18] During the construction of the Gotthard Tunnel in Switzerland (1871–81), a large number of miners suffered from severe anaemia of unknown cause.[19][20] Medical investigations let to the understanding that it was caused by Ancylostoma duodenale (favoured by high temperatures and humidity) and to "major advances in parasitology, by way of research into the aetiology, epidemiology and treatment of ancylostomiasis".[20]

Hookworms still account for high proportion of debilitating disease in the tropics and 50–60,000 deaths per year can be attributed to this disease.[21][22]

-

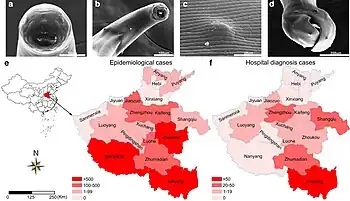

![Distribution of epidemiological and hospital cases by province,China[23]](./_assets_/0c70a452f799bfe840676ee341124611/Ancylostomiasis.jpg) Distribution of epidemiological and hospital cases by province,China[23]

Distribution of epidemiological and hospital cases by province,China[23] -

![An epidemic of "miner's anaemia" caused by Ancylostoma duodenale among workers constructing the Gotthard Tunnel contributed to the understanding of ancylostomiasis.[20]](./_assets_/0c70a452f799bfe840676ee341124611/Gotthardtunnel_Bauzug.jpg)

-

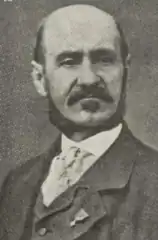

![Intestinal parasites among patients (Egypt)2019-2021;Positive detection rates of intestinal parasites determined by the commercial faecal parasite concentrators[24]](./_assets_/0c70a452f799bfe840676ee341124611/Ancylostomiasis_detection.jpg) Intestinal parasites among patients (Egypt)2019-2021;Positive detection rates of intestinal parasites determined by the commercial faecal parasite concentrators[24]

Intestinal parasites among patients (Egypt)2019-2021;Positive detection rates of intestinal parasites determined by the commercial faecal parasite concentrators[24]

History

In terms of history we find that Ancylostomiasis was first discovered by Angelo Dubini, an Italian physician, in 1838. He provided the first detailed description of hookworms during an autopsy on a woman who had died in Milan. Later, in 1898, Arthur Looss, another Italian physician, discovered Ancylostoma duodenale, one of the hookworms responsible for the disease.[25][26]

At the start of the 20th century, during the 1910s, common treatments for hookworm included thymol, 2-naphthol, chloroform, gasoline, and eucalyptus oil.[27]

By the 1940s, the treatment of choice was tetrachloroethylene, given as 3 to 4 cc in the fasting state, followed by 30 to 45 g of sodium sulfate. Tetrachloroethylene was reported to have a cure rate of 80 percent for Necator infections, but 25 percent in Ancylostoma infections, requiring re-treatment.[28]

References

- ↑ "Ancylostomiasis (Concept Id: C0002831) - MedGen - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ↑ Xu, Fang Fang; Niu, Yu Fei; Chen, Wen Qing; Liu, Sha Sha; Li, Jing Ru; Jiang, Peng; Wang, Zhong Quan; Cui, Jing; Zhang, Xi (14 October 2021). "Hookworm infection in central China: morphological and molecular diagnosis". Parasites & Vectors. 14 (1): 537. doi:10.1186/s13071-021-05035-3. ISSN 1756-3305. PMC 8518228. PMID 34649597.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 Aziz, Mochamad Helmi; Ramphul, Kamleshun (2025). "Ancylostoma". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 29939675. Archived from the original on 2024-04-28. Retrieved 2025-05-22.

- ↑ "Orphanet: Ankylostomiasis". www.orpha.net.

- ↑ "Definition of ANCYLOSTOMIASIS". www.merriam-webster.com. Archived from the original on 12 July 2024. Retrieved 28 May 2025.

- ↑ "14. Appendix 1: List of diseases covered by Industrial Injuries Disablement Benefit: B4 Ankylostomiasis...". Guidance: Industrial Injuries Disablement Benefits: technical guidance. UK Department for Work & Pensions. 20 May 2015. Archived from the original on 4 November 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2021. Archived 4 November 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Stracke, Katharina; Jex, Aaron R.; Traub, Rebecca J. (July 2020). "Zoonotic Ancylostomiasis: An Update of a Continually Neglected Zoonosis". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 103 (1): 64–68. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.20-0060. ISSN 1476-1645. PMC 7356431. PMID 32342850.

- ↑ Hochedez P, Caumes E (July 2008). "Common skin infections in travelers". Journal of Travel Medicine. 15 (4): 252–62. doi:10.1111/j.1708-8305.2008.00206.x. PMID 18666926.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 "Hookworm Infection - Infectious Diseases". MSD Manual Professional Edition. Retrieved 18 May 2025.

- ↑ "Hookworm (ancylostomiasis)" (PDF). texas.gov. Retrieved 28 May 2025.

- ↑ "Creeping eruption: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov.

- ↑ Sherman, Angel (26 November 2018). Medical Parasitology. Scientific e-Resources. p. 289. ISBN 978-1-83947-353-1.

- ↑ "Hookworm Disease Treatment & Management: Approach Considerations, Pharmacologic Therapy, Prevention". eMedicine. 2 March 2025. Retrieved 2 June 2025.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "Clinical Care of Zoonotic Hookworm". Zoonotic Hookworm. 22 April 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ↑ Holzer, B.R.; Frey, F.J. (February 1987). "Differential efficacy of mebendazole and albendazole against Necator americanus but not for Trichuris Trichiura infestations". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 32 (6): 635–37. doi:10.1007/BF02456002. PMID 3653234. S2CID 19551476.

- ↑ Wecker, Lynn (31 May 2018). Brody's Human Pharmacology: Mechanism-Based Therapeutics. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 551. ISBN 978-0-323-59662-6.

- ↑ Grove, David I (2014). Tapeworms, lice and prions: a compendium of unpleasant infections. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 1–602. ISBN 978-0-19-964102-4.

- ↑ Grove, David I (1990). A history of human helminthology. Wallingford: CAB International. pp. 1–848. ISBN 0-85198-689-7.

- ↑ Bugnion, E. (1881). "On the epidemic caused by Ankylostomum among the workmen in the St. Gothard Tunnel". British Medical Journal. 1 (1054): 382. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.1054.382. JSTOR 25256433. PMC 2263460. PMID 20749811.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Peduzzi, R.; Piffaretti, J.-C. (1983). "Ancylostoma duodenale and the Saint Gothard anaemia". Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 287 (6409): 1942–45. doi:10.1136/bmj.287.6409.1942. JSTOR 29513508. PMC 1550193. PMID 6418279.

- ↑ "Hookworms: Ancylostoma spp. and Necator spp". Archived from the original on 27 October 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-30. Archived 2008-10-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Clements, Archie C. A.; Alene, Kefyalew Addis (1 January 2022). "Global distribution of human hookworm species and differences in their morbidity effects: a systematic review". The Lancet Microbe. 3 (1): e72 – e79. doi:10.1016/S2666-5247(21)00181-6. ISSN 2666-5247. PMID 35544117. Retrieved 30 May 2025.

- ↑ LI, Rui; GAO, Jie; GAO, Lingxi; LU, Yajun (2019). "A Half-Century Studies on Epidemiological Features of Ancylostomiasis in China: A Review Article". Iranian Journal of Public Health. 48 (9): 1555–1565. PMC 6825681. PMID 31700811.

- ↑ Omar, Marwa; Abdelal, Heba O. (June 2022). "Current status of intestinal parasitosis among patients attending teaching hospitals in Zagazig district, Northeastern Egypt". Parasitology Research. 121 (6): 1651–1662. doi:10.1007/s00436-022-07500-z. ISSN 1432-1955. PMC 9098593. PMID 35362743.

- ↑ Dubini, Angelo (1843). "Nuovo verme intestinale umano (Agchylostoma duodenale), costituente un sesto genere dei Nematoidei proprii dell'uomo" [New human intestinal worm (Ancylostoma duodenale), constituting a sixth genus of the human nematoids]. Annali Universali di Medicina (in Italian). 106: 5–13. Archived from the original on 2024-04-21. Retrieved 2025-05-25.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ Chapman, Paul R.; Giacomin, Paul; Loukas, Alex; McCarthy, James S. (9 December 2021). "Experimental human hookworm infection: a narrative historical review". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 15 (12): e0009908. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0009908. ISSN 1935-2735. PMC 8659326. PMID 34882670.

- ↑ Milton, Joseph Rosenau (1913). Preventive Medicine and Hygiene. D. Appleton. p. 119. Archived from the original on 2022-11-11. Retrieved 2021-10-09.

- ↑ "Clinical Aspects and Treatment of the More Common Intestinal Parasites of Man (TB-33)". Veterans Administration Technical Bulletin 1946 & 1947. 10: 1–14. 1948. Archived from the original on 2022-02-25. Retrieved 2021-10-09. Archived 2022-02-25 at the Wayback Machine

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |