Greater trochanteric pain syndrome

| Greater trochanteric pain syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Trochanteric bursitis; lateral hip pain | |

| Specialty | Orthopedics |

| Symptoms | Pain outer aspect of hip[1] |

| Usual onset | >40 yrs[2] |

| Causes | Often unclear[1] |

| Risk factors | Overuse, injury, obesity, scoliosis, unequal leg lengths, IT band syndrome, prior hip surgery[2][3] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, examination, supported by medical imaging[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Femoroacetabular impingement, iliotibial band syndrome, stress fracture, sciatica[3] |

| Treatment | Changing activities, NSAIDs, physiotherapy, steroid injections[2] |

| Prognosis | Improvement over mths[1] |

| Frequency | Relatively common[1] |

Greater trochanteric pain syndrome (GTPS) involves inflammation near the hip, specifically the greater trochanter.[1] Symptoms include pain to the outer aspect of the hip; thought, the buttock or thigh may also be involved.[1] Pain is worse with exercise, after a period of rest, or crossing the legs.[1][2] It may result in limping or a popping feeling.[3]

The cause if often unclear.[1] Risks include overuse, injury, obesity, scoliosis, unequal leg lengths, IT band syndrome, and prior hip surgery.[2][1] The underlying mechanism may involve inflammation of the bursa or tendons.[1] Diagnosis is generally based on symptoms and examination, supported by medical imaging.[2]

Initial management may involve changing activities, NSAIDs, physiotherapy, or steroid injections.[2] Activity should be increased slowly.[1] Improvement may take a year.[1] If this is not effective, occasionally surgery maybe an option.[2]

Greater trochanteric pain syndrome is relatively common.[1] Females (15%) are more commonly affected than males (8%).[1][3] It most commonly occurs in peoples over 40 years old.[1][2] It appears to be more common in high income countries.[3] The condition was first described in 1923 by Stegemann.[4]

Signs and symptoms

The primary symptom is hip pain, especially hip pain on the outer (lateral) side of the joint.[1] This pain may appear when walking or lying down on that side.[1]

Cause

The condition includes within it trochanteric bursitis, snapping hip syndrome, and abductor tendinopathy.[3]

Diagnosis

A doctor may begin the diagnosis by asking the patient to stand on one leg and then the other, while observing the effect on the position of the hips. Palpating the hip and leg may reveal the location of the pain, and range-of-motion tests can help to identify its source.

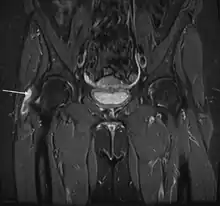

X-rays, ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging may reveal tears or swelling. But often these imaging tests do not reveal any obvious abnormality in patients with documented GTPS.[5]

Prevention

Because wear on the hip joint traces to the structures that support it (the posture of the legs, and ultimately, the feet), proper fitting shoes with adequate support are important to preventing GTPS. For someone who has flat feet, wearing proper orthotic inserts and replacing them as often as recommended are also important preventive measures.

Strength in the core and legs is also important to posture, so physical training also helps to prevent GTPS. But it is equally important to avoid exercises that damage the hip.[6]

Treatment

Conservative treatments have a 90% success rate and can include any or a combination of the following: pain relief medication, NSAIDs, physiotherapy, shockwave therapy (SWT) and corticosteroid injection. Surgery is usually for cases that are non-respondent to conservative treatments and is often a combination of bursectomy, iliotibial band (ITB) release, trochanteric reduction osteotomy or gluteal tendon repair.[7] A 2011 review found that traditional nonoperative treatment helped most patients, low-energy SWT was a good alternative, and surgery was effective in refractory cases and superior to corticosteroid therapy and physical therapy.[8] There are case reports in which surgery has relieved GTPS, but its effectiveness is not documented in clinical trials as of 2009.[9]

The primary treatment is rest. This does not mean bed rest or immobilizing the area but avoiding actions which result in aggravation of the pain. Icing the joint may help. A non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug may relieve pain and reduce the inflammation. If these are ineffective, the definitive treatment is steroid injection into the inflamed area.

Physical therapy to strengthen the hip muscles and stretch the iliotibial band can relieve tension in the hip and reduce friction. The use of point ultrasound may be helpful, and is undergoing clinical trials.[10]

In extreme cases, where the pain does not improve after physical therapy, cortisone shots, and anti-inflammatory medication, the inflamed bursa can be removed surgically. The procedure is known as a bursectomy. Tears in the muscles may also be repaired, and loose material from arthritic degeneration of the hip removed.[6] At the time of bursal surgery, a very close examination of the gluteal tendons will reveal sometimes subtle and sometimes very obvious degeneration and detachment of the gluteal tendons. If this detachment is not repaired, removal of the bursa alone will make little or no difference to the symptoms.

The bursa is not required, so the main potential complication is potential reaction to anaesthetic. The surgery can be performed arthroscopically and, consequently, on an outpatient basis. Patients often have to use crutches for a few days following surgery up to a few weeks for more involved procedures.

See also

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 "Greater trochanteric pain syndrome". NHS inform. Archived from the original on 4 November 2024. Retrieved 15 October 2025.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 "Hip Bursitis". www.orthoinfo.org. OrthoInfo - AAOS. Archived from the original on 26 September 2025. Retrieved 16 October 2025.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Pumarejo Gomez, L; Li, D; Childress, JM (January 2025). "Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome (Greater Trochanteric Bursitis)". StatPearls. PMID 32491365.

- ↑ Hugo, D.; de Jongh, H. R. (January 2012). "Greater trochanteric pain syndrome". SA Orthopaedic Journal. 11 (1): 28–33. ISSN 1681-150X. Retrieved 16 October 2025.

- ↑ Dougherty C, Dougherty JJ (August 27, 2008). "Evaluating hip pathology in trochanteric pain syndrome". The Journal of Musculoskeletal Medicine. Archived from the original on July 27, 2009. Retrieved August 3, 2022.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Dougherty C, Dougherty JJ (November 1, 2008). "Managing and preventing hip pathology in trochanteric pain syndrome". Archived from the original on March 14, 2010. Retrieved August 3, 2022.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Reid, Diane (March 2016). "The management of greater trochanteric pain syndrome: A systematic literature review". Journal of Orthopaedics. 13 (1): 15–28. doi:10.1016/j.jor.2015.12.006. PMC 4761624. PMID 26955229.

- ↑ Lustenberger, David P; Ng, Vincent Y; Best, Thomas M; Ellis, Thomas J (September 2011). "Efficacy of Treatment of Trochanteric Bursitis: A Systematic Review". Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine. 21 (5): 447–453. doi:10.1097/JSM.0b013e318221299c. PMC 3689218. PMID 21814140.

- ↑ Williams BS, Cohen SP (2009). "Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome: A Review of Anatomy, Diagnosis and Treatment". Anesthesia & Analgesia. 108 (5): 1662–1670. doi:10.1213/ane.0b013e31819d6562. PMID 19372352. S2CID 5521326.

- ↑ Clinical trial number NCT01642043 for "Point-of-Care Ultrasound in Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome" at ClinicalTrials.gov

External links

| Classification |

|---|