A History of Japanese Mathematics/Chapter 3

CHAPTER III.

The Development of the Soroban.

Before proceeding to a consideration of the third period of Japanese mathematics, approximately the seventeenth century of the Christian era, it becomes necessary to turn our attention to the history of the simple but remarkable calculating machine which is universal in all parts of the Island Empire, the soroban. This will be followed by a chapter upon another mechanical aid known as the sangi, since each of these devices had a marked influence upon higher as well as elementary mathematics from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century.[1]

The numeral systems of the ancients were so unsuited to the purposes of actual calculation that probably some form of mechanical calculation was always necessary. The fact is the more evident when we consider that convenient writing material was a late product, papyrus being unknown in Greece for example before the seventh century B. C., parchment being an invention of the fifth[2] century B. C., paper being a relatively late product,[3] and metal and stone being the common media for the transmission of written knowledge in the earlier centuries in China. On account of the crude numeral systems of the ancients and the scarcity of convenient writing material, there were invented in very early times various forms of the abacus, and this instrumental arithmetic did not give way to the graphical in western Europe until well into the Renaissance period.[4] In eastern Europe it never has been replaced, for the tschotii is used everywhere in Russia today, and when one passes over into Persia the same type of abacus[5] is common in all the bazaars. In China the swan-pan is universally used for purposes of computation, and in Japan the soroban is as strongly entrenched as it was before the invasion of western ideas.

The Japanese soroban is a comparatively recent invention, having been derived from the Chinese swan-pan (Fig. 10), which is also relatively modern. The earlier means employed in China are known to us chiefly through the masterly work of Mei Wen-ting (1633-1721)[6] entitled Kou-swan-k’i-k’ao.[7] Mei Wen-ting was one of the greatest Chinese mathematicians, the author of upwards of eighty works or memoirs, and one of the leading writers on the history of mathematics among his people. He tells us that the early instrument of calculation was a set of rods, ch’eou.[8] The earliest definite information that we have of the use of these rods is the Han Shu (Records of the Han Dynasty), which was written by Pan Ku of the Later Han period, in the year 80 of our era. According to him the ancient arithmeticians used comparatively long rods,[9] and the commentary of Sou Lin on the Han history tells us that two hundred seventy-one of these formed a set.[10] Furthermore, in the Che-chouo (Narrative of the Century), written by Lieou Yi-k’ing in the fifth century, it appears that ivory rods were used. We also find that the ancient ideograph for swan (reckoning) is 祘, a form that is manifestly derived from the rods, and that is evidently the source of the present Chinese ideograph. Mei Wen-ting says that it is impossible to give the origin of these rods, but he believes that the ancient classic, the Yih-king, gives evidence, in its mystic trigrams, of their very early use.[11] As to the size of the rods in ancient times we are not informed, none being now extant, but an early work on cooking, the Chong-k’ouei-lou, speaks of cutting pieces of meat 3 inches long, like a calculating rod, from which we get some idea of their length.

As to the early Chinese method of representing numbers, we have a description by Ts’ai Ch’en, surnamed, Kieou-fong (1167—1230), a philosopher of the Song dynasty. In his Hong-fan (Book of Annals) he gives the numerals as follows:

| I | II | III | IIII | IIIII | I | II | III | IIII | ... | I II | ... | II IIIII | IIII I | ... | I IIII | ... | IIII IIII |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 12 | 25 | 46 | 69 | 99 |

As to the methods of operating with the rods, Yang Houei, in his Siu-kou-Ch’ai-ki-Swan-fa of 1275 or 1276, gives the following example in multiplication:

| = | multiplier | = | 247 | ||||||

| = | multiplicand | = | 736 | ||||||

| = | product | = | 181 792 |

From China the calculating rods passed to Korea where the natives use them even to this day. These sticks are commonly made of bamboo, split into square prisms, and numbering about 150 in a set. They are kept in a bamboo case, although some are made of bone and are kept in a cloth bag as shown in the illustration, (Fig. 4.). The Korean represents his numbers from left to right, laying the rods as follows:

| I | II | III | IIII | X | XI | XII | XIII | XIIII | — | T[12] |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

When this transition took place is unknown nor is it material since the methods of using the two were the same.[14]

The method of representing the numbers by means of the sangi was the same as the one already described as having long been used by the Chinese. The units, hundreds, ten thousands, and so on for the odd places, were represented as follows:

| 𝍩 | 𝍪 | 𝍫 | 𝍬 | 𝍭 | 𝍮 | 𝍯 | 𝍰 | 𝍱 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

The tens, thousands, hundred thousands, and so on for the the even places, were represented as follows:

| 𝍠 | 𝍡 | 𝍢 | 𝍣 | 𝍤 | 𝍥 | 𝍦 | 𝍧 | 𝍨 |

| 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | 90 |

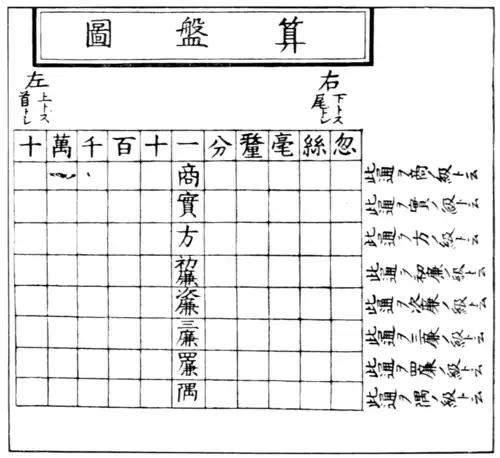

These numerals were arranged in a series of squares resembling our chess-board, called a swan-pan, although not at all like the Chinese abacus that bears this name. The following illustration (Fig. 6), taken from Satō Shigeharu's Tengen Shinan of 1698, shows its general form:

Fig. 6. The general form of the sangi board, from a work of 1698.

| 𝍫 | 𝍧 | 𝍤 | 𝍯 |

The number 1267, represented by the sangi without the ruled board. Is shown in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7. The number 1267 represented by sangi.

From representing the numbers by the sangi on a ruled board came a much later method of transferring the lines to paper, and using a circle to represent the vacant square. This could only have occurred after the zero had reached China and had been passed on to Japan, but the date is only a matter of conjecture. By this method, instead of having 38057 represented as shown above, we should have it written thus:

𝍫𝍧〇𝍤𝍯

In laying down the rods a red piece indicated a positive number and a black one a negative. In writing, however, a marked placed obliquely across a number indicated subtraction. Thus, 𝍫⃥ meant —3, and 𝍮⃥ meant —6.

The use of sangi in the fundamental operations may be illustrated by the following example in which we are required to find the shō (quotient) given the jitsu (dividend) 276, and the ho (divisor) 12.[15]

| shō | |||||

| jitsu | (276) | ||||

| hō | (12) |

First consider the jitsu as negative, indicating the fact in this manner:

| shō | |||||

| jitsu | |||||

| hō |

The first figure of the shō is evidently 2:

| shō | |||||

| jitsu | |||||

| hō |

Multiply the hō by 20, and put the product, 240, beside the jitsu, thus:

| shō | |||||

| jitsu | |||||

| hō |

which, by combining numbers in the jitsu, reduces to

| shō | ||||

| jitsu | ||||

| hō |

The hō is now advanced one place, exactly as was done in the early European plan of division by the galley method, after which the next figure of the shō is evidently 3, and the work appears as follows:

| shō | |||

| jitsu | |||

| hō |

Multiplying the hō by 3 the product, 36, is again written beside the jitsu, giving

| shō | ||

| jitsu | ||

| hō |

or

| shō | ||

a result which is written thus:

In order that the appearance of the sangi in actual use may be more clearly seen, a page from Nishiwaki Richyū's Sampō Tengen Roku of 1714 is reproduced in Fig. 8, and an illustration from Miyake Kenryū's Shojutsu Sangaku Zuye of 1795 in Fig. 9.

Fig. 8. Sangi board. From Nishiwaki Richyu's Sampō Tengen Roku of 1714.

In the later years of the sangi computation the custom of arranging the even places differently from the odd places changed, and instead of representing 38057 by the old method[16] as shown on page 25, it was represented thus:

| ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

This was done only on the ruled squares, however, the written form remaining as shown on page 25.

The transition from the ch'eou or rod calculation to the present form of abacus in China next demands our attention. Mei Wen-ting, whose name has already been mentioned, expresses regret that an exact date for the abacus cannot be

Fig. 9. From Miyake Kenryū's work of 1795.

fixed. He says, however, "If, in my ignorance, I may be allowed to hazard a guess, I should say that it began with the first years of the Ming Dynasty." This would be aboud 1384, when T'ai-tsou, the first Ming emperor, undertook to reform the calendar. At any rate, Mei Wen-ting concludes that in the reform of the calendar in 1281 rods were used, while in that of 1384 the abacus was employed. There is evidence, however, that the abacus was known in China in the twelfth century, but that it was not until the fourteenth that it was commonly used.[17] Since a division table such as is used in manipulating the swan-pan is given in a work by Yang Hui who flourished at the close of the Song Dynasty, in the latter half of the thirteenth century, we have reason to believe that the swan-pan was known at that time. Moreover we have the titles of several books such as Chou-pan Chi and Pan-chou Chi recorded in the Historical Records of the Song Dynasty, which seem to refer to this instrument. It must also be admitted that at least one much earlier work mentions "computations by means of balls," although this seems to have been only a

Fig. 10. The Chinese swan-pan, indicating the number 27091.

local plan known to but few. That the Roman abacus should have been known very early in China is not only probable but fairly certain, in view of the relations between China and Italy at the time of the Caesars.[18]

The Chinese abacus is known commonly as the swan-pan (swan-p'an, "reckoning table"). In southern China it is also known as the soo-pan,[19] and in Calcutta, where the Chinese shroſſs employ it, the name is corrupted to swinbon. The literary name is chou-p'an ("ball table" or "pearl table"). As will be seen by the illustration there are five balls below the line and two above, each of the latter counting as five. In the illustration (Fig. 10) the balls are placed to represent 27091.

Fig. 11. The soroban, indicating the number 90278 in the middle of the board.

The balls are called chou (pearls) or tse (son, child, grain), and are commonly spoken of as swan-pan chou-tse. The transverse bar is the leang (beam) or tsi-leang (spinal colum, also used to designate the ridge-pole of a roof). The columns are called wei (positions), hang (lines), or tang (steps, or bars). The left side is called ts'ien (front) and the right side heou (rear). This was the instrument that replaced the ancient rods about the year 1300, perhaps suggested by the ancient Roman abacus which it resembles quite closely, perhaps by some form of instrument in Central Asia, and perhaps invented by the Chinese themselves. The resemblance to the Roman form, and the known intercourse with the West, both favor the first of these hypotheses.

Just as the Japanese received the sangi from China, perhaps by way of Korea, so they received the abacus from the same source. They call their instrument by the name soroban, which some have thought to be a corruption of the Chinese swan-pan,[20] and others to have been derived from the word soroiban, meaning an orderly arranged table.[21]

The soroban is an improvement upon the swan-pan, as will be seen by the illustration. Instead of having two 5-balls it has only one, and it replaces the balls by buttons having a sharp edge that the finger easily engages without slipping. In the illustration (Fig. 11) the number 90278 is represented in the center of the soroban.

The invention of the soroban, or rather the importation and the improvement of the swan-pan, is usually assigned to the close of the sixteenth century, although we shall show that this is probably too late a date. In the Sampō Tamatebako, by Fukuda Riken, published in 1879, an account is given of the journey of one Mōri Kambei Shigeyoshi, a scholar of the sixteenth century, to China. Mōri was in his early days in the service of Lord Ikeda Terumasa, and was afterwards a retainer of the great hero Toyotomi Hideyoshi, better known as Taikō, who in the turbulent days of the close of the Ashikaga Shogunate[22] subdued the entire country, compelling peace by force of arms. The story goes that Taikō, wishing to make his court a center of learning, sent Mōri to China to acquire the imathematical knowledge that was wholly wanting in Japan at that period. Mōri, however, was a man of humble station, and his requests on behalf of his master were treated with such contempt that he returned to his native land with little to show for his efforts. Upon relating his trials and humiliation to Taikō, the latter bestowed upon him the title of Dewa no Kami, or Lord of Dewa. Again Mōri set out for China, but again he was destined to meet with some dissappointment, for hardly had he set foot on Chinese soil than Taikō began his invasion of Korea. China at once became involved in the defence of what was practically a vassal state, and as the war progressed it became more and more a matter of danger for a Japanese to reside within her borders. Mōri was not received with the favor that he had hoped for, and in due time returned to his native land. Although he had spent some time abroad, he had not accomplished his entire purpose. Nevertheless he brought back with him a considerable knowledge of Chinese mathematics, and also the swan-pan, which was forthwith developed into the present soroban. If the story is true, Mōri must have spent some years in China, for Taikō began his invasion in 1592 and died in 1598, and he was already dead when Mōri returned. Mōri repaired to the Castle of Ōsaka which Taikō had built and where he had lived, and there he was hospitably received by the son and successor of the great warrior. There he lived and wrote until the city was besieged in 1615, and the castle taken by Japan's greatest hero, Tokugawa Iyeyasu, founder of the Tokugawa shogunate, whose tomb at Nikkō is a Mecca for all tourists to that delightful region. We are told by Araki,[23] who lived at the beginning of the eighteenth century, that Mōri thence-forth taught the soroban arithmetic in Kyōto.

Although this story of Mōri's visit to China and of his introduction of the soroban is a recent one, it has been credited by some of the best writers in Japan.[24] Nevertheless there is a good deal of uncertainty about his journey,[25] and still more about his having been the one to introduce the soroban into Japan. Fukuda Riken who, as we have said, first published the story in 1879, gives no sources for his information. He received his information largely from his friend C. Kawakita, who tells the writers that it was Uchida Gokan who started the story of Mōri's first Chinese journey, claiming that he had read it once upon a time in a certain old manuscript that was in the library of Yushima, in Yedo. Unfortunately on the dissolution of the shogunate, at the time of the rise of the modern Empire, the books of this library were dispersed and the manuscript in question seems to have been irretrievably lost. That Uchida claims to have seen it we have been personally informed both by Mr. Kawakita and by Mr. N. Okamoto, to whom he told the circumstance. Nevertheless as historical evidence all this is practically worthless. Uchida was a learned man, but his reputation was not above reproach. He never told the story until the manuscript had disappeared, and no one has the slightest idea of the age, the character, or the reliability of the document. Moreover the older writers make no mention of this Chinese journey, as witness the Araki Son-yei Chadan which was written only a century after Mōri lived and which gives a sketch of his life and a brief statement concerning the early Japanese mathematics. In Murai's Sampō Dōshi-mon,[26] written nearly a century later still, no mention is made of the matter. Indeed, it is not until after the story was started by Uchida that we ever hear of it.[27]

But whether or not Mōri went to China, he did much for mathematics and he was an expert in the manipulation of the soroban. He was also possessed of a well-known Chinese treatise on the swan-pan, written by Ch'eng Tai-wei[28] and published in 1593,[29] a work that greatly influenced Japanese mathematics even long after Mōri's death. Mōri himself published a work on arithmetic in two books entitled Kijo Ranjō[30], and he left a manuscript on mathematics written in 1628.[31] Both have been lost, however, and of the contents of neither have we any knowledge. Mōri seems to have made a livelihood after the fall of Osaka by teaching arithmetic in Kyōto, where hundreds of pupils flocked to learn of him and study with the man who proclaimed himself "The first instructor in division in the world." He is said to have spent his last years at Yedo, the modern Tōkyō. Three of his pupils,[32] Yoshida Kōyū, Imamura Chishō, and Takahara Kisshu, known to their contemporaries as "The three Arithmeticians,"[33] did much to revive the study of the science in what we have designated as the third period of Japanese mathematics, and of them we shall speak more at length in a later chapter.

There are various reasons for believing that the swan-pan was not first brought to Japan by Mori. In the first place, such simple devices of the merchant class usually find their way through the needs of trade rather than through the efforts of the scholar. It was so with the Hindu-Arabic numerals in the West,[34] and it was probably so with the swan-pan in the East. There is a tradition that another Mori,[35] Mori Misaburō, an inhabitant of Yamada in the province of Ise, owned a swan-pan in the Bun-an Era, i. e., in 1444-1449. This instrument is still preserved and is now in the possession of the Kita-batake family.[36] It is also related that the great general and statesman Hosokawa Yūsai, in the time of Taiko, owned a smali ivory soroban, but of course this may have come from his contemporary Mōri Kambei. It is, however, reasonable to believe that, with the prosperous intercourse between China and Japan during the Ashikaga Shogunate, from the fourteenth to the end of the sixteenth centuries the swan-pan could not have failed to become known to the Japanese merchants, even if it was not extensively used by them. On the other hand, Mōri Kambei was the first great teacher of the art of manipulating it, so that much credit is due to him for its general adoption. We may, therefore, fix upon about the year 1600 as the beginning of the use of the soroban, and the century from 1600 to 1700 as the period in which it replaced the ancient bamboo rods.

Fig. 12. The soroban, indicating the number 987654321.

It is proper in this connection to give a brief description of the soroban and of the method of operating with it, particularly with a view to the needs of the Western reader. As already stated, the value of the ball above the beam is five, one being the value of each ball below the beam. In Fig. 12 the right-hand column has been used to represent units, the next one tens, and so on. In the picture these columns have been numbered by arranging the balls so that the units are 1, the tens 2, the hundreds 3, and so on. As a result, the number represented is 987654321.[37]

To add two numbers we have only to set down the first as in the illustration and then set down the second upon it. Thus to add 2 and 2, we put 2 balls at the top of the colunn and then 2 more, making 4. To add 2 and 3, we put 2 balls at the top, and then add 3; but since this makes 5 we push back the 5 balls and move down the one above the beam. To add 4 and 3, we take 4 balls; then we add the 3 by first adding 1, moving down the one above the beam to replace the 5, and then adding 2 more, leaving the five-ball and 2 unit balls. To add 7 and 6, we set down the 7 by moving the five-ball and 2 unit balls; we then move 3 more balls, which give us 10, and we indicate this by moving 1 ball in tens' column, clearing the units' column at the same time, and then we add 3 more, making ten and 3 units. It will be seen that as fast as any number is set down it is thereby added to the preceding sum, thus making the work very rapid in the hands of a skilled operator. Subtraction is evidently performed with equal ease.

For multiplying readily on the soroban it is necessary to learn the multiplication table. In this table the Japanese have two points of advantage over the Western peoples: (1) they do not use the words "times" or "equals", thus saving considerably in time and energy whenever they employ it; (2) they learn their products only one way, as 6 7's but not 7 6's. Thus their table for 6 is as follows:[38]

| Japanese names | In our figures | ||||

| ichi | roku | roku[39] | 1 | 6 | 6 |

| ni | roku | jū ni | 2 | 6 | 12 |

| san | roku[40] | jū hachi | 3 | 6 | 18 |

| shi | roku | ni jū shi | 4 | 6 | 24 |

| go | roku | san jū | 5 | 6 | 30 |

| roku | roku | san jū roku | 6 | 6 | 36 |

| roku | shichi | shi jū ni | 6 | 7 | 42 |

| roku | hachi[41] | shi jū hachi | 6 | 8 | 48 |

| roku | ku[42] | go jū shi | 6 | 9 | 54 |

This table reminds us of the one in common use by the Italian merchants from the fourteenth to the sixteenth century, and which was probably quite universal in the mercantile houses.

For purposes of historic interest we take to illustrate the process of multiplication an example from the Finko-ki of Yoshida, published in 1627, and described more fully in Chapter V. To multiply 625 by 16 the multiplier is placed to the left of the multiplicand on the soroban, a plan that is exactly opposite to the Chinese arrangement as set forth in the Suan-fa Tung-tsong of 1593. It represents one of the improvements

Fig. 13. 16625.

of Mori or of Yoshida, and has always been followed in Japan.

We first take the partial product 5 × 6 = 30 and place the 30 just to the right of the 625,[43] so that the soroban reads

1662530

Fig. 14. 1662530.

We now take 5 × 1 = 5 and add this 5 to the 3, making the product 80 thus far. The 5 of the 625 now having been multiplied by 16, it is removed, so that the figures stand as follows:

1662080

Fig. 15. 1662080.

The next step is the multiplication of 2 by 16, and this is done precisely as the 5 was multiplied. Expressed in figures the operation on the soroban is as follows:

| 1662080 | |

| 2 x 6 = | 12 |

| 2 x 1 = | 2 |

| Cancel 2 | 1660400 |

the 2 in 62080 being removed because the multiplication of 2 by 16 has been effected.

Fig. 16. 1660400.

The next step is the multiplication of 6 by 16, and the work appears on the soroban as follows:—

| 1660400 | |

| 6 x 6 = | 36 |

| 1 x 6 = | 6 |

| 1610000 |

Fig. 17. 1610000.

The process of division is much more complicated, and requires the perfect memorizing of a table technically known as the Ku ki hō, or "Nine Returning Method." It is given here only for 2, 6, and 7.[44]

[45] The table is not so unintelligible as it seems to a stranger, and in fact its use has certain advantages over Western me-thods. In the first place it is not encumbered with such words as "divided by" or "contained in," and in the second place it is not carried beyond the point where the dividend number as expressed in the table equals the divisor. It is in fact merely a table of quotients and remainders. Consider, for example, the table for 7. This states that

| 10:7 | = 1, and 3 remainder |

| 20:7 | = 2, and 6 remainder |

| 30:7 | = 4, and 2 remainder |

| 40:7 | = 5, and 5 remainder |

| 50:7 | = 7, and 1 remainder |

| 60:7 | = 8, and 4 remainder |

| 70:7 | = 10 |

Taking again an example from the classical work of Yoshida, let us divide 1234 by 8. These numbers will be represented on the soroban in the usual way, and placed as follows:

81234

The table now gives "8 1 12", meaning that 10:8 = 1, with a remainder 2. We therefore leave the 1 untouched and add 2 to the next figure, the numbers then appearing as follows:

81434

where the I represents the first figure in the quotient, and 434 represents the next dividend.

The table now tells us "8 4 50", meaning that 8 = 5 with no remainder. We therefore remove the first 4 and put 5 in its place, the soroban now indicating

81534

where 15 represents the first two figures in the quotient, and 34 represents the next dividend.

The table now tells us "8 3 36", meaning that 30:8 = 3 with a remainder 6. This means that the next figure of the quotient is 3, and that we have 6+4 still to divide. The soroban is therefore arranged to indicate

8153 (10)

But 8 = I with a remainder 2, so the soroban is arranged to indicate

81542

meaning that the quotient is 154 and the remainder is 2. We may now consider the result is 154 1⁄4 or we may continue the process and obtain a decimal fraction.

If the divisor has two or more figures it is convenient to have the following table in addition to the one already given:

| 1 | with | 1, | make it | 91 |

| 2 | with„ | 2, | make„ it„ | 92 |

| 3 | with„ | 3, | make„ it„ | 93 |

| 4 | with„ | 4, | make„ it„ | 94 |

| 5 | with„ | 5, | make„ it„ | 95 |

| 6 | with„ | 6, | make„ it„ | 96 |

| 7 | with„ | 7, | make„ it„ | 97 |

| 8 | with„ | 8, | make„ it„ | 98 |

| 9 | with„ | 9, | make„ it„ | 99 |

This means that 10:1 = 9 and 1 remainder, a = 9 and 2 remainder, and so on.

We shall sketch briefly the process of dividing 289899 by 486 as given by Yoshida. Arrange the soroban to indicate

486289899.

The table gives "4 2 50", so we change the 2 to 5 and arrange the soroban to indicate the following:

| 486589899 | |

| 5 x 8 = | 40 |

| 5 x 6 = | 30 |

| 486546899 |

Here 5 is the first figure of the quotient and 46899 is the remainder to be divided. Looking now at the last table we find "4 4 94" prime prime so we change the 4 to 9 and add 4 to the following digit. The soroban is arranged to indicate the following:

| 486546899 | |

| Then | 486596899 |

| Add 4 | 4 |

| Then 9 x 8 = | 72 |

| 9 x 6 = | 54 |

| Subtract 72 and 54 | 486593159 |

Here 59 is the first part of the quotient and 3159 is the remainder to be divided.

Proceeding in the same way, the next figure in the quotient is 6, and the soroban indicates

| 486 | 596759 |

| 486 | 596243 |

| 486 | 5965 |

and the quotient is 596.5.

Fig. 18. From the work of Fujiwara Norikaze, 1825.

This method of division is that given in the Finkō-ki, but in 1645 another plan was suggested by a well-known teacher, Momokawa Chubei.[46] This was the Shōjoho, or method of division by the aid of the ordinary multiplication table, as in written arithmetic. Momokawa sets it forth in a work entitled Kamei-zan (1645), and thenceforth the method itself bore this name. This plan, like the Jinkōki, is fundamentally a Chinese

Fig. 19. From an anonymous Kroaisanki of the seventeenth century.

method, as it appears in the Suan fa Tung-tsong of 1593, but it has never been so popular in Japan as the one given by Yoshida in the Jinkōki.

It is hardly worth while to consider the method of extracting roots by the help of the soroban, since the general theory does not differ from the one used in the West, and the subsidiary operations have been sufficiently explained.

Although the soroban began to replace the bamboo rods soon after 1600, it took more than a century for the latter to disappear as means for computation, and, as we shall see, they continued to be used for about two hundred years longer in connection with algebraic work. In Isomura Kittoku's Sampō Ketsugi-shō of 1660 (second edition 1684), and Sawaguchi's Kokon Sampō-ki of 1670, for example, we find both the rods

Fig. 20. From Miyake Kenryū's work of 1795.

and the soroban explained, and in another work of 1693 only the rods are given. The Tengen Shinan, by Satō Shigeharu, printed in 1698, also gives only the rods, as does the Kwatsuyo Sampō (Method of Mathematics) which Araki Hikoshirō Sonyei, being old, caused his pupil Ōtaka Yoshimasa to prepare in 1709.[47] In Murata Tsushin's Wakan Sampō, published in 1743, both systems are used, and in a primary arithmetic printed in 1781 only the rods are employed, so that we see that it was a long time before the soroban completely replaced the more ancient method of computation. In general we may say that all algebras used the sangi in connection with the "celestial element" method of solving equations, explained in the next chapter, while little by little the soroban replaced them for arithmetical work. The pictures of children learning to use the soroban are often interesting, as in the one from the arithmetic of Fujiwara Norikaze, of 1825 (Fig. 18). The early pictures of the use of the instrument in mercantile affairs are also curious, as in Fig. 19, taken from an anonymous work of the seventeenth century. An illustration of a pupil learning the use of the soroban, from Miyake Kenryū's work of 1795[48] is shown in Fig. 20.

- ↑ The literature of these forms of the abacus is extensive. The following are some of the more important sources: Vissière, A., Recherches sur l'origine de l'abaque chinois, in Bulletin de Giographie. Paris 1892; Knott, C. G., The Society of Japan, Yokohama 1886, vol. 14, p. 18; Goschkewitsch, J., Ueber das Chinesiche Rechenbrett, in the Arbeiten der Kaiserlich Russischen Gesandschaft zu Peking, Berlin 1858, vol. I, p. 293 (no history); van Name, R., On the Abacus of China and Japan, Journal of the American Oriental Society, 1875, vol. X, proc., p. CX; Rodet, L., Le souan-pan des Chinois, Bulletin de la Societé mathematique de France, 1880, vol. VIII; de la Couperie, A. T., The Old Numerals, the Counting Rods, and the Swan-pan, Numismatic Chronicle, London 1883, vol. III (3), p. 297; Hayashi, T., A brief history of Japanese Mathematics, part I, p. 18; Hübner, M., Die charakteristichen Formen des Rechenbretts, Zeitschrift für Lehrmittelwesen etc., Wien 1906, II. Jahrg., p. 47 (not historical). There is also an extensive literature relating to other forms of the abacus.

- ↑ Pliny says of the second century B. C.

- ↑ It seems to have been brought into Europe by the Moors in the twelfth century.

- ↑ See Smith, D. E., Rara Arithmetica, Boston 1909, index under Counters.

- ↑ Known in Armenia as the choreb, in Turkey as the coulba.

- ↑ Surnamed Ting-kieou and Wou-ngan. He lived in the brilliant reign of Kang-hi, who had been educated partly under the influence of Jesuit missionaries.

- ↑ Researches on ancient calculating instruments. See Vissière, loc. cit., p. 7, from whom I have freely quoted; Wylie, A., Notes on Chinese Literature, p. 91.

- ↑ There is not space in this work to enter into a discussion of the possible earlier use of knotted cords, a primitive system in many parts of the world. Lao-tze “the old philosopher”, refers to them in his Tao-teh-king, a famous classic of the sixth century B. C., saying: “Let the people return to knotted cords (chieng-shing) and use them.” See the English edition by Dr. P. Carus. Chicago, 1898, pp. 137, 272, 323.

- ↑ The text say 6 units (inches) but we do not know the length of the unit (inch) of that period.

- ↑ The old word means, possibly, a handful.

- ↑ The date of the Yih-king or Book of Changes in uncertain. It is often spoken of as Antiquissimus Sinarum liber, as in an edition by Julius Mohl, Stuttgart, 1834—9, 2 vols. It is ascribed to Fuh-hi (B. C. 3322) the fabled founder of the nation. There is an extensive literature upon this subject.

- ↑ We are indebted to an educated Korean, Mr. C. Cho, of the Methodist Publishing House in Tokio, for this information. On the mathematics of Korea in general, see Lowell, P., The Land of the Morning Calm. Boston 1886, p. 250. One of the leading classics of the country is the Song yang hoei soan fa, or Song tang houi san pep (Treatise on Arithmetic by Yang Hoei of the Song Dynasty), written in 1275 by Yang Hoei, whose literary name was Khien Koang; see M. Courant, Bibliographie Coréenne. Paris 1896, vol. III, p. 1.

- ↑ Hayashi, T. A brief history of the Japanese Mathematics, in the Nieuw Archief voor Wiskunde, tweede Reeks, zesde en sevende Deel, part I, p. 18.

- ↑ Indeed it is not certain that there was a sudden change from one to the other or that the names signified two different forms. The old Chinese names were ch’eon (which is the Japanese sangi) and t’sê, and these were used as synonymous.

- ↑ These examples are taken from Hayashi's History.

- ↑ Called Son-shi-Reppu-hō, the Method of arrangement of Sun-tsu.

- ↑ Vissière, Loc. cil.; Mikami, Y., A Remark on the Chinese Mathematics in Cantor's Geschichte der Mathematik, Archiv der Mathematik und Physik, vol. XV (3), Heft 1.

- ↑ See Smith and Karpinski, loc. cit., p. 79.

- ↑ Bowring, J., The Decimal System, London 1854, p. 193.

- ↑ Knott, loc. cit., p. 45.

- ↑ Oyamada, Matsunoya Hikki.

- ↑ This just preceded the Tokugawa shogunate, which lasted from 1603 to 1868.

- ↑ In the Araki Son-yei Chadan, or Stories told by Araki (Hikoshiro) Son-yei (1640-1718).

- ↑ Endō, Book I, p. 45-46, 54-56; Hayashi, History, p. 30, and his biographical sketch of Seki Kōwa in the Honchō Sūgaku Kōenshū (Lectures on the Mathematics of Japan, 1908, pp. 8—10.

- ↑ For example, Alfred Westphal claims that it was Korea rather than China that Mori visited. See his Beitrag zur Geschichte der Mathematik, in the Mittheilungen der deutschen Gesellschaft für Natur- und Völkerkunde Ostasiens in Tōkyō, ІХ. Heft, 1876. The Chinese journey is looked upon as fic tion by the learned C. Kawakita, who has studied very carefully the biographies of the Japanese mathematicians

- ↑ Book I, chapter on the Origin of Arithmetic, published in 1781.

- ↑ The oldest manuscript that we have found that speaks of it is Shiraishi's Sūka Fimmei-Shi, but since the author was a contemporary of Uchida he probably simply related the latter's story.

- ↑ Erroneously given in Endō as Ju Szŭ-pu. Book 1, p. 45.

- ↑ The Suan-fa T'ung-tsong.

- ↑ The Kijohō method of division on the soroban, described later. See Murai, Sampō Dōshi-mon, 1781, Book 1; and Endō, Book I, p. 45.

- ↑ This fact is recorded in an anonymous manuscript entitled Sanwa Zui. hitsu, which relates that the original manuscript, signed and sealed by Mōri himself, was in the possession of a mathematician named Kubodera early in the nineteenth century.

- ↑ See Endō, Book I, p. 55, and the Araki Son-yei Chadan.

- ↑ Also as the San-shi, or "three honorable scholars."

- ↑ See Smith and Karpinski, loc. cit., p. 114

- ↑ Not Mōri, however.

- ↑ It was exhibited not long ago in Tōkyō. We are indebted for this information to Mr. N. Okamoto.

- ↑ The best description of this instrument, in English, is that given by Knott, loc. cit., p. 45.

- ↑ Knott, loc. cit., p. 50.

- ↑ This is usually stated as "in roku ga roku," the ichi being corrupted to in and the ga inserted for euphony.

- ↑ Corrupted to sabu roku.

- ↑ The hachi is abbreviated to ha in this case, for euphony.

- ↑ Roku ku may here be abbreviated to rokku.

- ↑ In general, the units' figure of this product is placed as many columns to the right as there are figures in the multiplier.

- ↑ Knott, loc. cil., as corrected by Mr. Mikami

- ↑ 2 This and some others are given in the usual abridged form.

- ↑ Endō gives his personal name as Jihei, but this is open to doubt.

- ↑ It was printed in 1712.

- ↑ The first edition was 1716.