Toxic oil syndrome

| Toxic oil syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

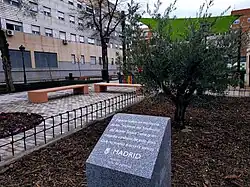

| Plaque to the victims of the Toxic Oil Syndrome | |

| Specialty | Rheumatology |

Toxic oil syndrome (TOS) or simply toxic syndrome (Spanish: síndrome del aceite tóxico or síndrome tóxico) is a musculoskeletal disease. A 1981 outbreak in Spain which affected more than 20,000 people, with over 330 dying within a few months and a few thousand remaining disabled, is thought to have been caused by contaminated colza (rapeseed) oil. It was unique because of its size, the novelty of the clinical condition, and the complexity of its aetiology. Its first appearance was as a lung disease, with unusual features, though the symptoms initially resembled a lung infection. The disease appeared to be restricted to certain geographical localities, and several members of a family could be affected, even while their neighbours had no symptoms. Following the acute phase, a range of other chronic symptoms was apparent.[1]

Investigation

In 1987, TOS was found by epidemology to have been linked to the ingestion of a "food-grade" rapeseed oil containing aniline derivatives. Two separate studies on levels of fatty acid anilides (which would arise from reaction between aniline and fats) confirmed that case-related oils have an elevated level of this substance. In 1991, Posada de la Paz et al. found that French rapeseed oil was imported to Spain after denaturation with 2% aniline, allegedly for industrial use.[2] (Spanish regulations of the time allowed imports of rapeseed oil only for industrial use, and only if it has been denatured with aniline to prevent use as food.)[1] They concluded that the toxic oil was produced from this industrial oil, illegally refined to remove aniline, and mixed with other edible oils. In 1992, the WHO published a review on the knowledge on the incident up to that point.[2]

During the 1990s, improved chemical methods found a new class of chemicals in multiple samples of toxic oil: 3-(N-phenylamino)-1,2-propanediol (abbreviated as PAP) and its esters, which would also be produced as aniline reacts with triglycerides. The factory responsible for illegally refining the oil was identified as Industria Trianera de Hidrogenación (ITH) of Seville.[2]

The WHO has since then tried to re-create the poisoning in laboratory animals with less-than-satisfactory results.[2] Specifically, three possible causative agents of TOS are PAP (3-(N-phenylamino)-1,2-propanediol), the 1,2-dioleoyl ester of PAP (abbreviated OOPAP), and the 3-oleoyl ester of PAP (abbreviated OPAP). These three compounds are formed by means of similar chemical processes, and oil that contains one of the three substances is likely to contain the other two.[3] Oil samples that are suspected to have been ingested by people who later developed TOS often contain all three of these contaminants (among other substances), but are most likely to contain OOPAP.[3] However, when these three substances were given to laboratory animals, OOPAP was not acutely toxic, PAP was toxic only after injection, but not after oral administration, and OPAP was toxic only after injection of high doses.[3] Therefore, none of these three substances is thought to cause TOS.[3] Similar results were obtained after administration of fatty acid anilides.[3]

Alternative theory

Dr. Antonio Muro, director of the Del Rey Hospital, was one of the first professionals to question the government's version that the avalanche of cases that were collapsing hospitals was due to the bacteria Mycoplasma Pneumoniae.[4] On December 16, 1984, a cover of the magazine 'Cambio 16' accused the pharmaceutical company Bayer of having caused the toxic syndrome crisis through the use of organophosphate pesticides through tomatoes sold in street markets. This further fueled the number of alternative theories about the outbreak, coupled with statements from some of the affected relatives who claimed that the sick had never consumed the toxic rapeseed oil.[5] These theories often claim that the USAF in Torrejón de Ardoz was involved in the origin of the epidemic.[6]

In October 2011, coroner Luis Frontela stated in an interview with the newspaper ABC that, when informing Professor Vetorazi, secretary of the World Health Organization, that the toxic syndrome was not due to rapeseed oil, but to the ingestion of pesticides (a hypothesis that the aforementioned forensic doctor always maintained against the official version that arose from the judicial process) and according to Luis Frontela, the secretary had replied that "they already knew about it".[7] Frontela himself tried to replicate the disease in monkeys with both pesticides and rapeseed oil, but without results in both scenarios, due to the different digestive and immunological systems of humans and the other primates.[8] Because of this, experimental studies performed in a variety of laboratory animals failed to reproduce the symptoms of human TOS.[3]

However, multiple studies have confirmed the causal relationship between rapeseed oil and the aforementioned mass poisoning.[9][10][11][12]

See also

- Eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome

- Ginger Jake

- Health crisis

- The Jungle

- List of food contamination incidents

References

- 1 2 Terracini, B. (27 May 2004). "The limits of epidemiology and the Spanish Toxic Oil Syndrome". International Journal of Epidemiology. 33 (3): 443–444. doi:10.1093/ije/dyg010. PMID 15166211.

- 1 2 3 4 Gelpí E, de la Paz MP, Terracini B, Abaitua I, de la Cámara AG, Kilbourne EM, Lahoz C, Nemery B, Philen RM, Soldevilla L, Tarkowski S (May 2002). "The Spanish toxic oil syndrome 20 years after its onset: a multidisciplinary review of scientific knowledge". Environmental Health Perspectives. 110 (5). US National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health: 457–464. doi:10.1289/ehp.110-1240833. PMC 1240833. PMID 12003748.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Toxic oil syndrome: ten years of progress (PDF). Copenhagen: WHO, Regional Office for Europe. 2004. ISBN 9789289010634. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-02-09.

- ↑ "Cientos de muertos y decenas de miles de afectados por la "colza"". archivodelatransicion (in Spanish). Retrieved 2025-10-10.

- ↑ Woffinden, Bob (25 August 2001). "Cover-up". The Guardian. Londres.

- ↑ Humanitatem, Ad (2009-09-23). "AD HUMANITATEM: LA "COLZA" Y LAS ARMAS BACTEREOLOGICAS DEL IMPERIO EN ESPA~NA: EL PRECIO DE SER COLONIA YANQUI". AD HUMANITATEM. Retrieved 2025-10-10.

- ↑ "Luis Frontela Carreras, catedrático de Medicina legal". ABC. 8 October 2011.

- ↑ Yoldi, José (1988-03-08). "Los peritos de la acusación descalifican el estudio de Frontela sobre el síndrome tóxico". El País (in Spanish). ISSN 1134-6582. Retrieved 2025-10-10.

- ↑ Alarcón, Julio Martín (2021-09-05). "Sí fue el aceite de colza, Iker: el verdadero engaño es tu 'teoría' sobre el síndrome tóxico". elconfidencial.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 2025-10-10.

- ↑ Gelpí, Emilio; de la Paz, Manuel Posada; Terracini, Benedetto; Abaitua, Ignacio; de la Cámara, Agustín Gómez; Kilbourne, Edwin M.; Lahoz, Carlos; Nemery, Bénoit; Philen, Rossanne M.; Soldevilla, Luis; Tarkowski, Stanislaw; WHO/CISAT Scientific Committee for the Toxic Oil Syndrome. Centro de Investigación para el Síndrome del Aceite Tóxico. "The Spanish toxic oil syndrome 20 years after its onset: a multidisciplinary review of scientific knowledge". Environmental Health Perspectives. 110 (5): 457–464. doi:10.1289/ehp.110-1240833. ISSN 0091-6765. PMC 1240833. PMID 12003748.

- ↑ Posada de la Paz, M.; Philen, R. M.; Borda, A. I. (2001). "Toxic oil syndrome: the perspective after 20 years". Epidemiologic Reviews. 23 (2): 231–247. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a000804. ISSN 0193-936X. PMID 12192735.

- ↑ Ortega-Benito, J. M. (1992-01-01). "Spanish toxic oil syndrome: Ten years after the disaster". Public Health. 106 (1): 3–9. doi:10.1016/S0033-3506(05)80323-3. ISSN 0033-3506.

External links

- WHO Report: Toxic Oil Syndrome - Ten years of progress Archived 2010-05-03 at the Wayback Machine