Sulforaphane

| |

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

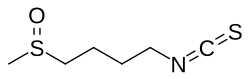

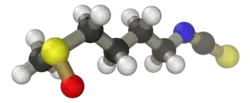

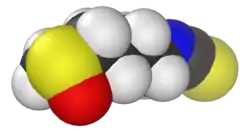

| Preferred IUPAC name

1-Isothiocyanato-4-(methanesulfinyl)butane | |

| Identifiers | |

CAS Number |

|

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

InChI

| |

SMILES

| |

| Properties | |

Chemical formula |

C6H11NOS2 |

| Molar mass | 177.29 g/mol |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |

Sulforaphane (sometimes sulphoraphane in British English) is a phytochemical within the isothiocyanate group of organosulfur compounds.[1] Although sulforaphane research on cancer has been ongoing for many years, there is no good clinical evidence to indicate consuming sulforaphane-rich vegetables or dietary supplements provides any effect.[1][2]

Biosynthesis

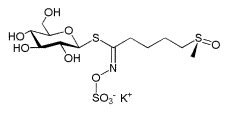

It is produced when the enzyme myrosinase transforms glucoraphanin, a glucosinolate, into sulforaphane upon damage to the plant (such as from chewing or chopping during food preparation), which allows the two compounds to mix and react.

Sulforaphane is present in cruciferous vegetables, such as broccoli, Brussels sprouts, and cabbage.Sulforaphane has two possible stereoisomers due to the presence of a stereogenic sulfur atom.[3]

Occurrence and isolation

Sulforaphane occurs in broccoli sprouts, which, among cruciferous vegetables, have the highest concentration of glucoraphanin, the precursor to sulforaphane.[1][4] It is also found in cabbage, cauliflower, Brussels sprouts, bok choy, kale, collards, mustard greens, and watercress.

Under conditions where broccoli is cooked, sulforaphane converts to the thiourea ((CH3SO(CH2)4NH)2CS) as well as some 1,2,4-trithiolane.[5]

Research

Although substantial animal research on the possible anti-cancer effects of sulforaphane has been reported, there is no substantial clinical research to indicate consuming foods rich in sulforaphane provides any benefit against cancer.[1]

See also

- Raphanin

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Isothiocyanates". Micronutrient Information Center, Linus Pauling Institute, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR. 2025. Retrieved 21 January 2025.

- ↑ Higdon J, Delage B, Williams D, Dashwood R (2007). "Cruciferous vegetables and human cancer risk: Epidemiologic evidence and mechanistic basis". Pharmacological Research. 55 (3): 224–236. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2007.01.009. PMC 2737735. PMID 17317210.

- ↑ Vanduchova A, Anzenbacher P, Anzenbacherova E (2019). "Isothiocyanate from Broccoli, Sulforaphane, and Its Properties". Journal of Medicinal Food. 22 (2): 121–126. doi:10.1089/jmf.2018.0024. PMID 30372361.

- ↑ Houghton CA, Fassett RG, Coombes JS (November 2013). "Sulforaphane: translational research from laboratory bench to clinic". Nutrition Reviews. 71 (11): 709–726. doi:10.1111/nure.12060. PMID 24147970.

- ↑ Jin Y, Wang M, Rosen RT, Ho CT (1999). "Thermal Degradation of Sulforaphane in Aqueous Solution". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 47 (8): 3121–3123. Bibcode:1999JAFC...47.3121J. doi:10.1021/jf990082e. PMID 10552618.