Pneumococcal pneumonia

| Pneumococcal pneumonia | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Streptococcus pneumoniae pneumonia[1] | |

| |

| |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Fever,cough,shortness of breath,chest pain[3] |

| Complications | Lung abscess, empyema[4] |

| Causes | Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteria[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Physical exam,X-ray, and sputum culture[5][6] |

| Differential diagnosis | Haemophilus influenzae,[7] Klebsiella pneumoniae, Legionnaires' disease |

| Prevention | Pneumococcal vaccine[8] |

| Treatment | Antibiotics [3] |

Pneumococcal pneumonia is a type of bacterial pneumonia that is caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus).[3] It is the most common bacterial pneumonia found in adults, the most common type of community-acquired pneumonia, and one of the common types of pneumococcal infection. [9]Once pneumococcal pneumonia has been identified, antibiotics will be prescribed.[3]

The estimated number of Americans with pneumococcal pneumonia is 900,000 annually, with almost 400,000 cases hospitalized and fatalities accounting for 5-7% of these cases.[9]

Symptoms and signs

The symptoms of pneumococcal pneumonia can occur suddenly, presenting as a severe chill, followed by a severe fever, cough, shortness of breath, rapid breathing, and chest pains. Other symptoms like nausea, vomiting, headache, fatigue, and muscle aches could also accompany initial symptoms;[3] the coughing can occasionally produce rusty or blood-streaked sputum.

Complications

Among the possible complications that an individual can have we find:[4]

- Airway blockage

- Collapsed lungs

- Lung abscesses

- Empyema

Mechanism

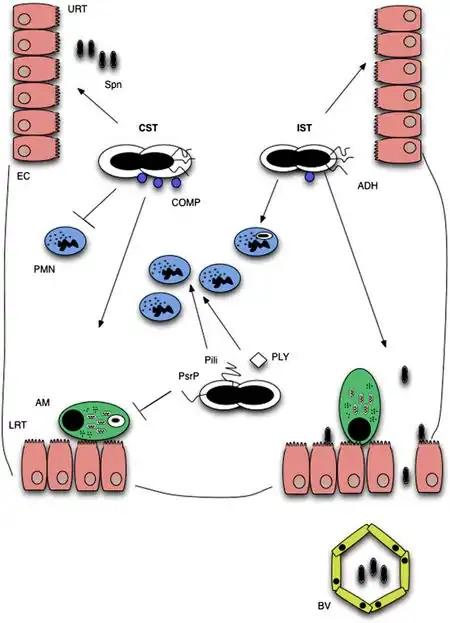

Three stages can be used to categorize the infection process of pneumococcal pneumonia: transmission, colonization, and invasion.[11] The Streptococcus pneumoniae (S. pneumoniae) leave the colonized host via shedding in order to be transmissible to new hosts, and must survive in the environment until infection of a new host (unless direct transmission occurs).[12]

Transmission

In order for transmission to occur, there must be close contact with a carrier or amongst carriers.[11] The likelihood of this increases during colder, dryer months of the year.Transmission via the secretions of carriers can result from direct interpersonal contact or contact with a contaminated surface.[11] Bacteria on contaminated surfaces can be easily cultured. In conditions with sufficient nutrients, pneumococci can survive for 24 hours[13] and avoid desiccation for multiple days.[12]

Reduced transmission has been observed amongst children with Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) immunization as acquisition of a new strain of S. pneumoniae is inhibited by pre-existing colonization.[11]

For successful acquisition in a new host, pneumococcus must successfully adhere to the mucous membrane of the new host's nasopharynx.[12] Pneumococcus is able to evade detection by the mucous membrane when there is a higher proportion of negatively charged capsules. This clearance is mediated by Immunoglobulin A1 (IgA1) which is abundant on the URT mucosal surfaces.[11]

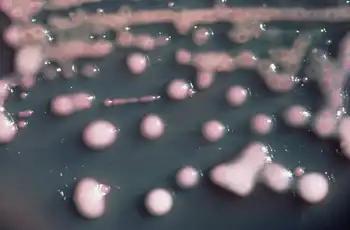

Colonization

Transparent and opaque colony morphology has been observed for pneumococci.[14] Airway colonization is observed in transparent phenotypes of serotypes, while survival in bloodstreams is observed for opaque phenotypes. Colonizable strains exhibit resistance against neutrophilic immune response.[15]

Successful colonization requires S. pnuemoniae to evade detection by the nasal mucus and attach to epithelial surface receptors.[11] Asymptomatic colonization occurs when S. pneumoniae bind to N-acetyl-glucosamine on epithelium without inflammation.[15] However, co-infection with a pre-existing inflammatory URT infection results in an over-expression of the epithelial receptors utilized by S. pneumoniae, thus increasing the likelihood of colonization. Neuraminidase also increases instances of epithelial binding through its cleavage of N-acetylneuraminic acid, glycolipids, glycoproteins, and oligosaccharides.[15]

Invasion

Initial colonization of the nasopharynx is typically asymptomatic, but invasion occurs when the bacteria spreads to other parts of the body including the lungs, blood, and brain. Interactions between Phosphorylcholine (ChoP) components on colonized epithelial cells allow for docking of choline binding proteins (CBPs), most notably CbpA. Colonization of the respiratory tract, and thus pneumonia cannot occur without CpbA.[16]

The pneumococcus moves across the mucosal barrier by integrating itself with the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor (pIgR), which is used by mucosal epithelial cells to transport IgA and IgM to the apical surface. Following its cleavage at the apical surface, pIgR, and subsequently the pneumococcus, move back to the basolateral surface allowing invasion of the upper respiratory tract.[16]

The pneumococcus then moves to invade the lower respiratory tract, evading the mucociliary escalator with the assistance of neuraminidase.[16]

Diagnosis

The evaluation of Pneumococcal pneumonia, per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, can be done via:[6][5]

- Medical history

- Physical exam

- Chest X-rays

- Blood tests

- Sputum analysis

- Urine test

Differential diagnosis

In terms of the DDx in an affected individual we find the following:[7]

- Haemophilus influenzae

- Klebsiella pneumoniae

- Legionnaires' disease

- Staphylococcal infections

Prevention

In terms of the prevention of Pneumococcal pneumonia we find that Pneumococcal vaccine is recommended for high-risk individuals. Additionally, hand washing and a healthy lifestyle(quit smoking, eat healthy diet) are beneficial as well for prevention.[8]

Treatment

.jpg)

Antibiotics usually alleviate and eliminate symptoms between 12 and 36 hours after the initial dose. Despite most antibiotics' effectiveness in treating the disease, sometimes the bacteria can resist the antibiotics, causing symptoms to worsen. Age and health of the infected patient can also contribute to the effectiveness of the antibiotics. [3]

For Pneumococcal pneumonia, the first-line antibiotic treatment includes amoxicillin for non-severe cases[17]

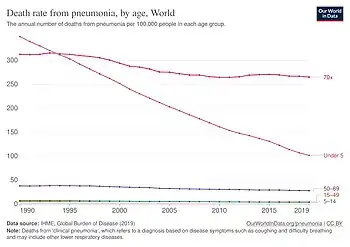

Epidemiology

S. pneumoniae is the leading cause of bacterial pneumonia globally and a primary pathogen for community-acquired pneumonia[18]Historically, S. pneumoniae caused 95 percent of all pneumonia cases before antibiotics. Currently, it accounts for 15 percent of pneumonia cases in the United States and 27 percent worldwide.[18]In 2021, S. pneumoniae was responsible for 28 percent of child pneumonia deaths, making it the leading pathogen.[19]

History

Pneumococcal pneumonia was discovered by the German bacteriologist Albert Fraenkel in the late 19th century. He identified Streptococcus pneumoniae as the causative agent of the disease. His work was important in advancing the understanding of bacterial infections and their impact on human health.[20]

Research

While it has been commonly known that the influenza virus increases one's chances of contracting pneumonia or meningitis caused by the streptococcus pneumonaie bacteria, new medical research in mice indicates that the flu is actually a necessary component for the transmission of the disease. Researcher Dimitri Diavatopoulo from the Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre in the Netherlands describes his observations in mice, stating that in these animals, the spread of the bacteria only occurs between animals already infected with the influenza virus, not between those without it. He says that these findings have only been inclusive in mice.[21]

References

- ↑ File Jr, T. M. (2006). "Clinical implications and treatment of multiresistant Streptococcus pneumoniae pneumonia". Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 12 (s3): 31–41. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01395.x. ISSN 1469-0691. PMID 16669927. Retrieved 14 May 2025.

- ↑ "Death rate from pneumonia, by age". Our World in Data. Archived from the original on 23 July 2025. Retrieved 29 July 2025.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 "Pneumococcal Pneumonia". www.niaid.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-09-09. Retrieved 2016-04-26. Archived 2016-09-09 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Pneumococcal Disease Symptoms and Complications". Pneumococcal Disease. 12 April 2024. Archived from the original on 6 March 2025. Retrieved 16 May 2025. Archived 6 March 2025 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Pneumonia - Diagnosis | NHLBI, NIH". www.nhlbi.nih.gov. 24 March 2022. Archived from the original on 11 May 2025. Retrieved 18 May 2025. Archived 11 May 2025 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Diagnosis and Treatment of Pneumococcal Disease | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 17 July 2023. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 8 December 2023. Archived 10 December 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Pneumococcal Infections (Streptococcus pneumoniae) Differential Diagnoses". emedicine.medscape.com. Archived from the original on 26 May 2025. Retrieved 15 May 2025.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Prevention". NIH. 24 March 2022. Archived from the original on 4 February 2024. Retrieved 17 May 2025. Archived 4 February 2024 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Pneumococcal Disease | Facts About Pneumonia | CDC". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 2023-04-06. Retrieved 2016-04-26. Archived 2023-04-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Dockrell, David H.; Whyte, Moira K. B.; Mitchell, Timothy J. (1 August 2012). "Pneumococcal Pneumonia: Mechanisms of Infection and Resolution". Chest. 142 (2): 482–491. doi:10.1378/chest.12-0210. ISSN 0012-3692. PMC 3425340. PMID 22871758.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 Weiser, Jeffrey N.; Ferreira, Daniela M.; Paton, James C. (29 March 2018). "Streptococcus pneumoniae: transmission, colonization and invasion". Nature Reviews Microbiology. 16 (6): 355–367. doi:10.1038/s41579-018-0001-8. ISSN 1740-1534. PMC 5949087. PMID 29599457.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Morimura, Ayumi; Hamaguchi, Shigeto; Akeda, Yukihiro; Tomono, Kazunori (2021). "Mechanisms Underlying Pneumococcal Transmission and Factors Influencing Host-Pneumococcus Interaction: A Review". Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 11: 639450. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2021.639450. ISSN 2235-2988. PMC 8113816. PMID 33996623.

- ↑ Verhagen, Lilly M.; Jonge, Marien I. de; Burghout, Peter; Schraa, Kiki; Spagnuolo, Lorenza; Mennens, Svenja; Eleveld, Marc J.; Jongh, Christa E. van der Gaast-de; Zomer, Aldert; Hermans, Peter W. M.; Bootsma, Hester J. (2014-02-25). "Genome-Wide Identification of Genes Essential for the Survival of Streptococcus pneumoniae in Human Saliva". PLOS ONE. 9 (2): e89541. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...989541V. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0089541. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3934895. PMID 24586856.

- ↑ Dockrell, David H.; Whyte, Moira K. B.; Mitchell, Timothy J. (2012-08-01). "Pneumococcal Pneumonia: Mechanisms of Infection and Resolution". Chest. 142 (2): 482–491. doi:10.1378/chest.12-0210. ISSN 0012-3692. PMC 3425340. PMID 22871758.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Bogaert, D; de Groot, R; Hermans, PWM (2004-03-01). "Streptococcus pneumoniae colonisation: the key to pneumococcal disease". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 4 (3): 144–154. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(04)00938-7. ISSN 1473-3099. PMID 14998500.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Loughran, Allister J.; Orihuela, Carlos J.; Tuomanen, Elaine I. (18 March 2019). "Streptococcus pneumoniae: Invasion and Inflammation". Microbiology Spectrum. 7 (2): 10.1128/microbiolspec.GPP3–0004–2018. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.GPP3-0004-2018. ISSN 2165-0497. PMC 6422050. PMID 30873934.

- ↑ Metlay, Joshua P.; Waterer, Grant W.; Long, Ann C.; Anzueto, Antonio; Brozek, Jan; Crothers, Kristina; Cooley, Laura A.; Dean, Nathan C.; Fine, Michael J.; Flanders, Scott A.; Griffin, Marie R.; Metersky, Mark L.; Musher, Daniel M.; Restrepo, Marcos I.; Whitney, Cynthia G. (1 October 2019). "Diagnosis and Treatment of Adults with Community-acquired Pneumonia. An Official Clinical Practice Guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 200 (7): e45 – e67. doi:10.1164/rccm.201908-1581ST. Archived from the original on 26 May 2025. Retrieved 23 May 2025.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Pahal, Parul; Rajasurya, Venkat; Nguyen, Andrew D. (2025). "Typical Bacterial Pneumonia". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 30485000. Archived from the original on 2025-04-13. Retrieved 2025-05-20. Archived 2025-04-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Global, regional, and national incidence and mortality burden of non-COVID-19 lower respiratory infections and aetiologies, 1990-2021: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 24 (9): 974–1002. September 2024. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(24)00176-2. ISSN 1474-4457. PMC 11339187. PMID 38636536.

- ↑ "Pneumonia | Special Collections | Library | University of Leeds". library.leeds.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 26 May 2025. Retrieved 21 May 2025.

- ↑ "Flu Infection Needed to Allow Spread of Pneumonia or Meningitis". LiveScience.com. 12 April 2011. Archived from the original on 2016-05-13. Retrieved 2016-04-26. Archived 2016-05-13 at the Wayback Machine