Bullous pemphigoid

| Bullous pemphigoid | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Specialty | Dermatology |

| Symptoms | Tense blisters, itch, red patches, urticaria[1] |

| Usual onset | Age 65 to 75-years[1] |

| Types | Vesicular pemphigus, pemphigoid vegetans, polymorphic pemphigus, pemphigoid excoriée, pemphigoid nodularis[2] |

| Causes | Autoimmune disorder[1] |

| Risk factors | Radiotherapy,[1] furosemide[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Appearance, blood test, biopsy, immunofluoresence[1] |

| Medication | Corticosteroids, azathioprine, mycophenolate[3] |

| Frequency | Age 65 to 75-years[1] |

Bullous pemphigoid is a chronic, blistering skin disease.[4] There are characteristically several large firm blisters on an urticarial base and with a tendency to occur in the groin, underarms, thighs, shins and inner surface of the arms.[1] It is usually itchy and there may be red and urticarial patches with central clearing.[1] Blisters may not always be present, especially early on in the course of the disease.[1] They may look like targets.[1] When the blisters burst, the skin may appear sore before it heals.[1]

It is an autoimmune disease.[1] Variants include vesicular pemphigus, pemphigoid vegetans, polymorphic pemphigus, pemphigoid excoriée, pemphigoid nodularis.[2] Large blisters form in the space between the epidermal and dermal skin layers. The disorder is a type of pemphigoid. It is classified as a type II hypersensitivity reaction, with the formation of anti-hemidesmosome antibodies.

It may occur at sites of radiation treatment, particularly in people with breast cancer.[5] It may occur over a burn or where there are patches of psoriasis.[1] Other triggers include medicines such as furosemide.[2]

Diagnosis is by its appearance and confirmed by biopsy and immunofluorescence.[1] In young girls with vulval involvement of BP, it may look like child abuse.[1] Other conditions that may appear similar include lichen planus pemphigoides and prurigo nodularis.[1] Treatment is generally with corticosteroids to begin with, with azathioprine and mycophenolate for longer term management.[3]

It occurs most often in the elderly with an onset typically around age 65 to 75-years.[1] When occurring in children, it typically occurs before the first birthday and lasts around 5-months.[1] The increased prevalence of bullous pemphigoid has been associated with an aging population and advancements in diagnostic methods.[4]

Signs and symptoms

Clinically, the earliest lesions may appear as a hives-like red raised rash, but could also appear dermatitic, targetoid, lichenoid, nodular, or even without a rash (essential pruritus).[6] Tense bullae eventually erupt, most commonly at the inner thighs and upper arms, but the trunk and extremities are frequently both involved.[1] Any part of the skin surface can be involved.[1] Oral lesions are present in a minority of cases.[7] The disease may be acute, but can last from months to years with periods of exacerbation and remission.[8] Several other skin diseases may have similar symptoms. However, milia are more common with epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, because of the deeper antigenic targets. A more ring-like configuration with a central depression or centrally collapsed bullae may indicate linear IgA disease. Nikolsky's sign is negative, unlike pemphigus vulgaris, where it is positive.[1]

-

.jpg)

-

.jpg)

-

.jpg)

-

.jpg)

-

Bullous pemphigoid

Bullous pemphigoid

Causes

In most cases of bullous pemphigoid, no clear precipitating factors are identified.[7] Potential precipitating events that have been reported include exposure to ultraviolet light and radiation therapy.[7][9] Onset of pemphigoid has also been associated with certain drugs, including furosemide, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, DPP-4 inhibitors, captopril, penicillamine, and antibiotics.[9]

Mechanism

The bullae are formed by an immune reaction, initiated by the formation of IgG[10] autoantibodies targeting dystonin, also called bullous pemphigoid antigen 1,[11] and/or type XVII collagen, also called bullous pemphigoid antigen 2,[12] which is a component of hemidesmosomes. A different form of dystonin is associated with neuropathy.[11] Following antibody targeting, a cascade of immunomodulators results in a variable surge of immune cells, including neutrophils, lymphocytes and eosinophils coming to the affected area. Unclear events subsequently result in a separation along the dermoepidermal junction and eventually stretch bullae.

Diagnosis

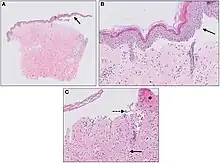

Diagnosis consist of at least 2 positive results out of 3 criteria (2-out-of-3 rule): (1) pruritus and/or predominant cutaneous blisters, (2) linear IgG and/or C3c deposits (in an n- serrated pattern) by direct immunofluorescence microscopy (DIF) on a skin biopsy specimen, and (3) positive epidermal side staining by indirect immunofluorescence microscopy on human salt-split skin (IIF SSS) on a serum sample.[14] Routine H&E staining or ELISA tests do not add value to initial diagnosis.

Differential diagnosis

Given its polymorphic nature, with presentations ranging from non-bullous features to blister formation, bullous pemphigoid requires an extensive differential diagnosis.[15] Considerations, specifically, are pemphigus foliaceus, pemphigus herpetiformis, linear IgA bullous dermatosis, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, bullous lupus erythematosus, eczema, urticaria, prurigo, impetigo, erythema multiforme, Sweet syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and autotoxic pruritus.[15]

Treatment

Treatments include topical steroids such as clobetasol, and halobetasol which in some studies have proven to be equally effective as systemic, or pill, therapy and somewhat safer.[7] However, in difficult-to-manage or widespread cases, systemic prednisone and powerful steroid-free immunosuppressant medications, such as methotrexate, azathioprine or mycophenolate mofetil, may be appropriate.[7][16] Some of these medications have the potential for severe adverse effects such as kidney and liver damage, increased susceptibility to infections, and bone marrow suppression.[17] Antibiotics such as tetracycline or erythromycin may also control the disease, particularly in patients who cannot use corticosteroids.[16] The anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab has been found to be effective in treating some otherwise refractory cases of pemphigoid.[18] A 2010 meta-analysis of 10 randomized controlled trials showed that oral steroids and potent topical steroids are effective treatments, although their use may be limited by side-effects, while lower doses of topical steroids are safe and effective for treatment of moderate bullous pemphigoid.[17]

IgA-mediated pemphigoid can often be difficult to treat even with usually effective medications such as rituximab.[19]

Monitoring

Clinicians ought to diligently observe changes in circulating coagulation markers in bullous pemphigoid individuals, including D-dimer, fibrinogen, and fibrin degradation products, as these fluctuations are essential to monitor.[20] Moreover, given the connection between coagulation and immune-inflammatory responses in bullous pemphigoid, focusing on shared pathways in treatment approaches may benefit individuals presenting with both bullous pemphigoid and a hypercoagulable condition.[20]

Prognosis

Bullous pemphigoid may be self-resolving in a period ranging from several months to many years even without treatment.[7] It may significantly compromise an individual's quality of life.[21] Poor general health related to old age is associated with a poorer prognosis.[7] While improvements have been made in therapeutic approaches, long-term management remains challenging, particularly for older adults with coexisting illnesses.[4]

Prevalence

Bullous pemphigoid ranks as the most prevalent autoimmune disorder causing subepidermal blistering.[22]

Epidemiology

It occurs most often in the elderly with an onset typically around age 65 to 75-years.[1] Its estimated frequency is seven to 14 cases per million per year, but has been reported to be as high as 472 cases per million per year in Scottish men older than 85.[7] At least one study indicates the incidence might be increasing in the United Kingdom.[23] Some sources report it affects men twice as frequently as women,[16] while others report no difference between the sexes.[7] Occurrence in children is uncommon.[24] The increased prevalence of bullous pemphigoid has been associated with an aging population and advancements in diagnostic methods.[4]

Many mammals can be afflicted, including dogs, cats, pigs, and horses, as well as humans. It is very rare in dogs; on average, three cases are diagnosed around the world each year.

Research

Animal models of bullous pemphigoid have been developed using transgenic techniques to produce mice lacking the genes for the two known autoantigens, dystonin and collagen XVII.[11][12]

Complement inhibitors, including nomacopan and avdoralimab, are actively being researched.[25] IL-17 and IL-23 inhibitors like secukinumab and tildrakizumab show potential in limited cases.[25] Neonatal Fc receptor antagonists, such as efgartigimod, are being studied, along with topical therapies and Janus kinase inhibitors.[25] These emerging alternative treatments, as of 2024, may improve bullous pemphigoid management while reducing reliance on systemic corticosteroids and associated toxicities.[25] However, their efficacy, safety, and appropriate dosing protocols for managing bullous pemphigoid have not been established.[25]

Nomacopan (rVA576), a dual inhibitor targeting C5 and leukotriene B4, has demonstrated promising outcomes in a phase II nonrandomized, controlled study (NCT04035733).[25] Out of nine participants, seven exhibited a significant reduction in BPDAI scores and pruritus within 1.5 months, without any serious adverse events.[25] In 2021, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial (NCT05061771) was initiated to recruit 148 patients and evaluate the efficacy of nomacopan in bullous pemphigoid treatment.[25] Participants were randomized to receive either nomacopan paired with oral corticosteroids or placebo with oral corticosteroids.[25] The treatment spanned 24 weeks.[25]

Avdoralimab, a targeted anti-C5aR1 monoclonal antibody, was evaluated in an open-label, randomized, case-controlled, multicenter, phase II clinical trial (NCT04563923) in 2020.[25] The trial, which involved 40 participants with bullous pemphigoid, compared treatment outcomes of avdoralimab combined with superpotent topical corticosteroids against using superpotent topical corticosteroids as a standalone therapy.[25]

See also

- List of target antigens in pemphigoid

- List of immunofluorescence findings for autoimmune bullous conditions

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 James, William D.; Elston, Dirk; Treat, James R.; Rosenbach, Misha A.; Neuhaus, Isaac (2020). "21. Chronic blistering dermatoses". Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology (13th ed.). Edinburgh: Elsevier. p. 461-463. ISBN 978-0-323-54753-6. Archived from the original on 2022-03-16. Retrieved 2022-03-15.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Johnstone, Ronald B. (2017). "6. Vesiculobullous reaction pattern". Weedon's Skin Pathology Essentials (2nd ed.). Elsevier. pp. 88–133. ISBN 978-0-7020-6830-0. Archived from the original on 2021-05-25. Retrieved 2022-03-18.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Wakelin, Sarah H. (2020). "22. Dermatology". In Feather, Adam; Randall, David; Waterhouse, Mona (eds.). Kumar and Clark's Clinical Medicine (10th ed.). Elsevier. pp. 686–687. ISBN 978-0-7020-7870-5. Archived from the original on 2022-03-21. Retrieved 2022-03-21.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Akbarialiabad, Hossein; Schmidt, Enno; Patsatsi, Aikaterini; Lim, Yen Loo; Mosam, Anisa; Tasanen, Kaisa; Yamagami, Jun; Daneshpazhooh, Maryam; De, Dipankar; Cardones, Adela Rambi G.; Joly, Pascal; Murrell, Dedee F. (20 February 2025). "Bullous pemphigoid". Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 11 (1). doi:10.1038/s41572-025-00595-5. PMID 39979318.

- ↑ Johnstone, Ronald B. (2017). "5. Spongiotic reaction pattern". Weedon's Skin Pathology Essentials (2nd ed.). Elsevier. pp. 68–87. ISBN 978-0-7020-6830-0. Archived from the original on 2021-05-25. Retrieved 2022-03-18.

- ↑ Cozzani E, Gasparini G, Burlando M, Drago F, Parodi A (May 2015). "Atypical presentations of bullous pemphigoid: Clinical and immunopathological aspects". Autoimmunity Reviews. 14 (5): 438–45. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2015.01.006. PMID 25617817.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 Culton DA, Liu Z, Diaz LA (17 October 2007). "Chapter 54. Bullous Pemphigoid". In Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, Paller AS, Leffell DJ (eds.). Fitzpatrick's Dermatology In General Medicine, Two Volumes (7th ed.). Mcgraw-hill. ISBN 978-0-07-146690-5. Archived from the original on 4 July 2014. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ↑ Longo, D (2012). Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. p. 427. ISBN 9780071632447.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Chan LS (2011). "Bullous Pemphigoid". EMedicine Reference. Archived from the original on 2011-11-10. Retrieved 2011-09-25.

- ↑ "Dorlands Medical Dictionary:bullous pemphigoid". Retrieved 2010-06-24.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): DYSTONIN; DST - 113810

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): COLLAGEN, TYPE XVII, ALPHA-1; COL17A1 - 113811

- ↑ Giang, Jenny; Seelen, Marc A. J.; van Doorn, Martijn B. A.; Rissmann, Robert; Prens, Errol P.; Damman, Jeffrey (2018). "Complement Activation in Inflammatory Skin Diseases". Frontiers in Immunology. 9: 639. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.00639. ISSN 1664-3224. PMC 5911619. PMID 29713318.

- ↑ Meijer JM, Diercks GF, de Lang EW, Pas HH, Jonkman MF (December 2018). "Assessment of diagnostic strategy for early recognition of bullous and nonbullous variants of pemphigoid". JAMA Dermatol. 155 (2): 158–165. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4390. PMC 6439538. PMID 30624575.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Miyamoto, Denise; Santi, Claudia Giuli; Aoki, Valéria; Maruta, Celina Wakisaka (9 May 2019). "Bullous pemphigoid". Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia. 94 (2): 133–146. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20199007. PMC 6486083. PMID 31090818.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 ""Bullous Pemphigoid." Quick Answers to Medical Diagnosis and Therapy". Archived from the original on 2001-07-26. Retrieved 2012-07-21.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Kirtschig G, Middleton P, Bennett C, Murrell DF, Wojnarowska F, Khumalo NP (October 2010). "Interventions for bullous pemphigoid". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (10): CD002292. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002292.pub3. PMC 7138251. PMID 20927731.

- ↑ Lamberts A, Euverman HI, Terra JB, Jonkman MF, Horváth B (2018). "Effectiveness and Safety of Rituximab in Recalcitrant Pemphigoid Diseases". Frontiers in Immunology. 9: 248. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.00248. PMC 5827539. PMID 29520266.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ↑ He, Yong; Shimoda, Michiko; Ono, Yoko; Villalobos, Itzel Bustos; Mitra, Anupam; Konia, Thomas; Grando, Sergei A.; Zone, John J.; Maverakis, Emanual (1 June 2015). "Persistence of Autoreactive IgA-Secreting B Cells Despite Multiple Immunosuppressive Medications Including Rituximab". JAMA Dermatology. 151 (6): 646–50. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.59. PMID 25901938.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Zhang, Bingjie; Yang, Nan; Li, Li (4 March 2025). "Bullous pemphigoid and hypercoagulability: a review". Expert Review of Clinical Immunology. 21 (3): 323–332. doi:10.1080/1744666X.2025.2450766. PMID 39772971.

- ↑ Werth, V. P.; Murrell, D. F.; Joly, P.; Ardeleanu, M.; Hultsch, V. (February 2025). "Bullous pemphigoid burden of disease, management and unmet therapeutic needs". Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 39 (2): 290–300. doi:10.1111/jdv.20313. PMC 11760689. PMID 39297242.

- ↑ Powers, Camille M.; Thakker, Sach; Gulati, Nicholas; Talia, Jordan; Dubin, Danielle; Zone, John; Culton, Donna A.; Hopkins, Zachary; Adalsteinsson, Jonas A. (February 2025). "Bullous pemphigoid: A practical approach to diagnosis and management in the modern era". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2025.01.086. PMID 39914667.

- ↑ Langan, S M; Smeeth, L; Hubbard, R; Fleming, K M; Smith, C J P; West, J (9 July 2008). "Bullous pemphigoid and pemphigus vulgaris--incidence and mortality in the UK: population based cohort study". BMJ. 337 (jul09 1): a180. doi:10.1136/bmj.a180. PMC 2483869. PMID 18614511.

- ↑ Witte, Mareike; Zillikens, Detlef; Schmidt, Enno (2 November 2018). "Diagnosis of Autoimmune Blistering Diseases". Frontiers in Medicine. 5. doi:10.3389/fmed.2018.00296. PMC 6224342. PMID 30450358.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ↑ 25.00 25.01 25.02 25.03 25.04 25.05 25.06 25.07 25.08 25.09 25.10 25.11 Karakioulaki, Meropi; Eyerich, Kilian; Patsatsi, Aikaterini (March 2024). "Advancements in Bullous Pemphigoid Treatment: A Comprehensive Pipeline Update". American Journal of Clinical Dermatology. 25 (2): 195–212. doi:10.1007/s40257-023-00832-1. PMC 10866767. PMID 38157140.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |