Ankyloglossia

| Tongue-tie | |

|---|---|

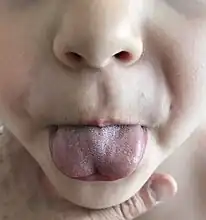

| Other names: Ankyloglossia | |

| |

| Adult with ankyloglossia | |

| Specialty | Pediatrics |

| Symptoms | None, difficulties with breastfeeding[1][2] |

| Complications | Poor mother child bonding[3] |

| Usual onset | Present at birth[3] |

| Causes | Unclear, genetics[4] |

| Risk factors | Family history, cocaine use[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Examination of attachment during breastfeeding[5] |

| Differential diagnosis | Cleft palate, nose obstruction, laryngomalacia[4] |

| Treatment | Time, breastfeeding specialist, cutting the frenulum[4] |

| Frequency | 4 to 11% of newborns[6] |

Ankyloglossia, also known as tongue-tie, is a condition present at birth that decreases movement of the tongue tip.[3] It may result in difficulties with breastfeeding, including breast pain or poor attachment.[1] Complications may include poor mother child bonding.[3] Effects on speech are unclear.[4]

It is due to an unusually short lingual frenulum, the membrane connecting the underside of the tongue to the floor of the mouth.[6] The cause is generally unclear; though, it may run in families or rarely occur as part of certain syndromes.[4][2] Cases vary in severity.[7] Diagnosis is based on examination of attachment during breastfeeding.[5]

Mild cases may resolve with time or support from a breastfeeding specialist.[4] Cutting the frenulum may improve pain from breastfeeding.[5] However, it is unclear if it affects overall frequency of breastfeeding or weight gain in the child.[5][6]

Tongue-tie is common, affecting about 4 to 11% of newborns.[6] Males may be more commonly affected than females.[4] Rates of operative management have increased more than 400% in the 10 years prior to 2023.[6] The condition was first clearly described about 2000 years ago by Cornelius Celsus.[2] The term is from the Greek “agkilos” meaning "curved" and “glossa” meaning "tongue".[2]

Signs and symptoms

Ankyloglossia can affect eating, especially breastfeeding, speech and oral hygiene[8] as well as have mechanical/social effects.[9] Ankyloglossia can also prevent the tongue from contacting the anterior palate. This can then promote an infantile swallow and hamper the progression to an adult-like swallow which can result in an open bite deformity.[10] It can also result in mandibular prognathism; this happens when the tongue contacts the anterior portion of the mandible with exaggerated anterior thrusts.[10]

Opinion varies regarding how frequently ankyloglossia truly causes problems. Some believe it is rarely symptomatic, whereas others believe it is associated with a variety of problems.[11]

-

Tongue tie in a 4 year old

Tongue tie in a 4 year old -

Heart-shaped deformity of the tongue due to tongue tie

Heart-shaped deformity of the tongue due to tongue tie

Feeding

Twenty-five percent of mothers of babies with ankyloglossia reported breastfeeding difficulty compared with 3% of the mothers without.[12] Babies with ankyloglossia do not, however, have such big difficulties when feeding from a bottle.[13]

They followed 10 infants with ankyloglossia who underwent surgical tongue-tie division. Eight of the ten mothers experienced poor infant latching onto the breast, 6/10 experienced sore nipples and 5/10 experienced continual feeding cycles; 3/10 mothers were exclusively breastfeeding. Following a tongue-tie division, 4/10 mothers noted immediate improvements in breastfeeding, 3/10 mothers did not notice any improvements and 6/10 mothers continued breastfeeding for at least four months after the surgery. The study concluded that tongue-tie division may be a possible benefit for infants experiencing breastfeeding difficulties due to ankyloglossia and further investigation is warranted. The limitations of this study include the small sample size and the fact that there was not a control group.[14]

Speech

Messner and Lalakea studied speech in children with ankyloglossia. They noted that the phonemes likely to be affected due to ankyloglossia include sibilants and lingual sounds such as 'r'. In addition, the authors also state that it is uncertain as to which patients will have a speech disorder that can be linked to ankyloglossia and that there is no way to predict at a young age which patients will need treatment. The authors studied 30 children from one to 12 years of age with ankyloglossia, all of whom underwent frenuloplasty. Fifteen children underwent speech evaluation before and after surgery. Eleven patients were found to have abnormal articulation before surgery and nine of these patients were found to have improved articulation after surgery. Based on the findings, the authors concluded that it is possible for children with ankyloglossia to have normal speech in spite of decreased tongue mobility. However, according to their study, a large percentage of children with ankyloglossia will have articulation deficits that can be linked to tongue-tie and these deficits may be improved with surgery. The authors also note that ankyloglossia does not cause a delay in speech or language, but at the most, problems with enunciation. Limitations of the study include a small sample size as well as a lack of blinding of the speech-language pathologists who evaluated the subjects’ speech.

Several recent systematic reviews and randomized control trials have argued that ankyloglossia does not impact speech sound development and that there is no difference in speech sound development between children who received surgery to release tongue-tie and those who did not.[15][16][17]

Messner and Lalakea also examined speech and ankyloglossia in another study. They studied 15 patients and speech was grossly normal in all the subjects. However, half of the subjects reported that they thought that their speech was more effortful than other peoples' speech.[9]

Mechanical effects

Ankyloglossia can result in mechanical and social effects.[9] Some noted mechanical limitations which included cuts or discomfort underneath the tongue and difficulties with kissing, licking one's lips, eating an ice cream cone, keeping one's tongue clean and performing tongue tricks. Mechanical and social effects may occur even without other problems related to ankyloglossia, such as speech and feeding difficulties. Also, mechanical and social effects may not arise until later in childhood, as younger children may be unable to recognize or report the effects. In addition, some problems, such as kissing, may not come about until later in life.[18]

Mouth breathing

Ankyloglossia most often prohibits the tongue from resting in its ideal posture, at the roof of the mouth. When the tongue rests at the roof of the mouth, it enables nasal breathing. A seemingly unrelated consequence of ankyloglossia is chronic mouth breathing. Mouth breathing is correlated with other health issues such as enlarged tonsils and adenoids, chronic ear infections, and sleep-disordered breathing.[19][20]

Teeth

Ankyloglossia is correlated to grinding teeth (bruxism) and temporomandibular joint (TMJ) pain. When the tongue normally rests at the roof of the mouth, it leads to the development of an ideal "U"-shaped palate. Ankyloglossia often causes a narrow, "V"-shaped palate to develop, which crowds teeth and increases the potential need for braces and possibly jaw surgery.[19][20][21]

Cause

The cause for tongue tie is unknown. While rearch suggests that tongue-tie could be heritable, most people with it have no inborn diseases.[22] There are associations between X-linked cleft palate syndrome and rare syndromes, including Kindler syndrome, Opitz syndrome, and Van Der Woude syndrome.[22]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis may be difficult; it is not always apparent by looking at the underside of the tongue, but is often dependent on the range of movement permitted by the genioglossus muscles. For infants, passively elevating the tongue tip with a tongue depressor may reveal the problem. For older children, making the tongue move to its maximum range will demonstrate the tongue tip restriction. In addition, palpation of genioglossus on the underside of the tongue will aid in confirming the diagnosis.[10]

Some signs of ankyloglossia can be difficulty speaking, difficulty eating, ongoing dental issues, jaw pain, or migraines.[23]

A severity scale for ankyloglossia, which grades the appearance and function of the tongue, is recommended for use in the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine.[24][25]

Treatment

Intervention include surgery in the form of frenotomy (also called a frenectomy or frenulectomy) or frenuloplasty.

A frenotomy can be performed as a standalone procedure or as part of another surgery. The procedure is typically quick and is performed under local anesthesia. First, the area under the tongue is numbed with an injection. Once the patient is numb, a small incision is made in the tissue and the tongue is freed from its tether. The incision is then closed with dissolvable sutures. Recovery is typically quick.

Surgery can be considered for patients of any age with a tight frenulum, as well as a history of speech, feeding, or mechanical/social difficulties. Adults with ankyloglossia may elect the procedure. Some of those who have done so report post-operative pain.

Horton et al.,[10] have a classical belief that people with ankyloglossia can compensate in their speech for a limited tongue range of motion. For example, if the tip of the tongue is restricted for making sounds such as /n, t, d, l/, the tongue can compensate through dentalization; this is when the tongue tip moves forward and up. When producing /r/, the elevation of the mandible can compensate for restriction of tongue movement. Also, compensations can be made for /s/ and /z/ by using the dorsum of the tongue for contact against the palate rugae. Thus, Horton et al.[10] proposed compensatory strategies as a way to counteract the adverse effects of ankyloglossia and did not promote surgery. Non-surgical treatments for ankyloglossia are typically performed by Orofacial Myology specialists, and involve using exercises to strengthen and improve the function of the facial muscles and thus promote the proper function of the face, mouth, and tongue.[26]

An alternative to surgery for children with ankyloglossia is to take a wait-and-see approach, which is more common if there are no impacts on feeding.[18] Ruffoli et al. report that the frenulum naturally recedes during the process of a child's growth between six months and six years of age.[27][28]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Bruney, TL; Scime, NV; Madubueze, A; Chaput, KH (May 2022). "Systematic review of the evidence for resolution of common breastfeeding problems-Ankyloglossia (Tongue Tie)". Acta paediatrica (Oslo, Norway : 1992). 111 (5): 940–947. doi:10.1111/apa.16289. PMID 35150472.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Ganesan, K; Girgis, S; Mitchell, S (April 2019). "Lingual frenotomy in neonates: past, present, and future". The British journal of oral & maxillofacial surgery. 57 (3): 207–213. doi:10.1016/j.bjoms.2019.03.004. PMID 30910412.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Rodriguez Lara, F; Carnino, JM; Levi, JR (July 2025). "Maternal Experiences and Challenges in Breastfeeding Infants with Tongue-Tie: A Systematic Review". Maternal and child health journal. 29 (7): 870–878. doi:10.1007/s10995-025-04102-w. PMID 40366606.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Becker, S; Brizuela, M; Mendez, MD (January 2025). "Ankyloglossia (Tongue-Tie)". StatPearls. PMID 29493920.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Finley, Caitlin. "#391 Trying Tongue-Tie Treatment: Does Frenotomy Fix Feeding Frustrations? – CFPCLearn". Archived from the original on 25 June 2025. Retrieved 25 June 2025.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Evans, L; Lawson, H; Oakeshott, P; Knights, F; Chadha, K (July 2023). "Tongue-tie and breastfeeding problems". The British journal of general practice : the journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners. 73 (732): 297–298. doi:10.3399/bjgp23X733221. PMID 37385756.

- ↑ Akintoye, Sunday O.; Mupparapu, Mel (2020). "Clinical evaluation and anatomic variation of the oral cavity". In Stoopler, Eric T.; Sollecito, Thomas P. (eds.). Oral Medicine in Dermatology, An Issue of Dermatologic Clinics. Vol. 38. Philadelphia: Elsevier. p. 409. ISBN 978-0-323-75480-4. Archived from the original on 2023-02-13. Retrieved 2023-02-13.

- ↑ Travis, Lee Edward (1971). Handbook of speech language pathology and audiology. New York, New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts Education Division Meredith Corporation.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Lalakea, M. Lauren; Messner, Anna H. (2003). "Ankyloglossia: The adolescent and adult perspective". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 128 (5): 746–52. doi:10.1016/s0194-5998(03)00258-4. PMID 12748571.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 Horton CE, Crawford HH, Adamson JE, Ashbell TS (1969). "Tongue-tie". The Cleft Palate Journal. 6: 8–23. PMID 5251442.

- ↑ Messner AH, Lalakea ML (2000). "Ankyloglossia: controversies in management". Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 54 (2–3): 123–31. doi:10.1016/S0165-5876(00)00359-1. PMID 10967382.

- ↑ Messner, Anna H.; Lalakea, M. Lauren; Aby, Janelle; Macmahon, James; Bair, Ellen (2000). "Ankyloglossia: Incidence and associated feeding difficulties". Archives of Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery. 126 (1): 36–9. doi:10.1001/archotol.126.1.36. PMID 10628708.

- ↑ Lalakea, M. Lauren; Messner, Anna H. (2002). "Frenotomy and frenuloplasty: If, when, and how". Operative Techniques in Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 13: 93–97. doi:10.1053/otot.2002.32157.

- ↑ Wallace, Helen; Clarke, Susan (2006). "Tongue tie division in infants with breast feeding difficulties". International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 70 (7): 1257–61. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2006.01.004. PMID 16527363.

- ↑ Wang, J; Yang, X; Hao, S; Wang, Y (May 8, 2021). "The effect of ankyloglossia and tongue-tie division on speech articulation: A systematic review". Int J Paediatr Dent. 32 (2): 144–156. doi:10.1111/ipd.12802. PMID 33964037. S2CID 233997867.

- ↑ Salt, H; Claessen, M; Johnston, T; Smart, S (July 2020). "Speech production in young children with tongue-tie". Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 134:110035: 110035. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2020.110035. PMID 32298924. S2CID 215801978.

- ↑ Chinnadurai, Sivakumar; Francis, David O.; Epstein, Richard A.; Morad, Anna; Kohanim, Sahar; McPheeters, Melissa (June 2015). "Treatment of Ankyloglossia for Reasons Other Than Breastfeeding: A Systematic Review". Pediatrics. 135 (6): e1467–74. doi:10.1542/peds.2015-0660. PMID 25941312. S2CID 10614311.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Lalakea ML, Messner AH (2003). "Ankyloglossia: does it matter?". Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 50 (2): 381–97. doi:10.1016/S0031-3955(03)00029-4. PMID 12809329.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Baxter, Richard (13 July 2018). Tongue-tied : how a tiny string under the tongue impacts nursing, feeding, speech, and more. Musso, Megan,, Hughes, Lauren,, Lahey, Lisa,, Fabbie, Paula,, Lovvorn, Marty,, Emanuel, Michelle. Pelham, AL. ISBN 978-1732508200. OCLC 1046077014.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ 20.0 20.1 Hang, William M.; Gelb, Michael (March 2017). "Airway Centric® TMJ philosophy/Airway Centric® orthodontics ushers in the post-retraction world of orthodontics". Cranio: The Journal of Craniomandibular Practice. 35 (2): 68–78. doi:10.1080/08869634.2016.1192315. ISSN 2151-0903. PMID 27356671.

- ↑ Yoon, Audrey; Zaghi, Soroush; Weitzman, Rachel; Ha, Sandy; Law, Clarice S.; Guilleminault, Christian; Liu, Stanley Y. C. (September 2017). "Toward a functional definition of ankyloglossia: validating current grading scales for lingual frenulum length and tongue mobility in 1052 subjects". Sleep & Breathing = Schlaf & Atmung. 21 (3): 767–775. doi:10.1007/s11325-016-1452-7. ISSN 1522-1709. PMID 28097623. S2CID 37361766.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Becker, Sarah; Brizuela, Melina; Mendez, Magda D. (2025). Ankyloglossia (Tongue-Tie). Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 29493920. Archived from the original on 2025-04-27. Retrieved 2025-06-25.

- ↑ "Symptoms and Best Treatments for Adults with Tongue Tie". Take Home Smile. 20 July 2022. Archived from the original on 2 August 2022. Retrieved 19 December 2022. Archived 2 August 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Hazelbaker AK: The assessment tool for lingual frenulum function (ATLFF): Use in a lactation consultant private practice Masters thesis, Pacific Oaks College, 1993

- ↑ ABM Protocols: Protocol #11: Guidelines for the evaluation and management of neonatal ankyloglossia and its complications in the breastfeeding dyad

- ↑ "The Ins and Outs of Tongue-Tie". OM Health. Archived from the original on 2014-11-07. Retrieved 2014-06-23. Archived 2014-11-07 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Harris EF, Friend GW, Tolley EA (1992). "Enhanced prevalence of ankyloglossia with maternal cocaine use". Cleft Palate Craniofac. J. 29 (1): 72–6. doi:10.1597/1545-1569(1992)029<0072:EPOAWM>2.3.CO;2. PMID 1547252.

- ↑ Ruffoli R, Giambelluca MA, Scavuzzo MC, et al. (2005). "Ankyloglossia: a morphofunctional investigation in children". Oral Diseases. 11 (3): 170–4. doi:10.1111/j.1601-0825.2005.01108.x. PMID 15888108.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Look up ankyloglossia in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |