Motivation and emotion/Book/2025/Vasopressin and motivation

How does vasopressin influence motivation?

Overview

On a crowded platform, someone shoving toward his partner shifts Luke from watchful to protective as a surge of vasopressin narrows attention and primes action. That night, sleep-deprived, the same AVP circuitry sustains patient, repetitive caregiving while he settles their newborn. Same peptide, different context - biasing social motivation toward defence and motivated care.

|

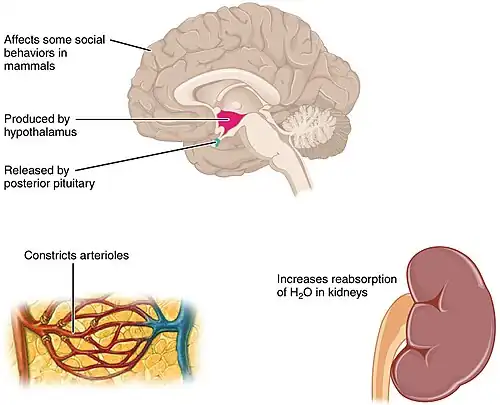

A surge in vasopressin can push social motivation in different directions - toward swift defence in threatening contexts and toward ongoing, patient effort in caregiving. This chapter explains how vasopressin (AVP) tunes motivational strength by linking social-behaviour networks with reward and stress systems, and why its effects differ by context, sex, and task demands (see Figure 1 for AVP production in hypothalamus, posterior pituitary release, vascular and renal effects, and social behaviors). Recent guiding research on vasopressin's role in motivation and social behaviour include:

- How the lateral septum integrates AVP with reward circuits to bias approach/avoidance and drug-reward sensitivity (Chen et al., 2024).

- How AVP and oxytocin circuits shape social motivation across contexts, with clear sex differences and translational implications (Rigney, de Vries, Petrulis, & Young, 2022).

- How SCN AVP neurons set the brain’s circadian pace, gating arousal/effort and motivational readiness across the day (Tsuno et al., 2023).

What this chapter shows:

- Show how AVP’s brain patterns and internal-state signals (e.g., stress) set the daily 'tone' of arousal and effort, shaping when we are most motivated to act.

- Explain where V1a and V1b receptors sit in social and reward circuitry, and how this placement lets AVP bias approach vs avoidance, cooperation vs competition, and persistence in goal pursuit.

- Distinguish context-dependent effects - why the same peptide can amplify caregiving and bonding in safe situations yet mobilise defensive/aggressive motivation under threat.

- Connect effects to human contexts, highlighting evidence strength, key limitations (methods, variability, mixed findings), and clinical implications.

|

Focus questions

|

AVP in the brain: sources, receptors, release

- Intro - Why these features matter for motivation: Where AVP is produced, which receptors it engages, and how it is released together determine whether it amplifies social salience, mobilises effort under stress, or supports persistence (Young & Wang, 2004; Dumais & Veenema, 2016)).

- Major sources - leverage over motivation: Magnocellular PVN/SON neurons (found in the hypothalmus) provide endocrine AVP and influence nearby hypothalamic networks; parvocellular PVN neurons project to brain targets and the median eminence (stress control); the SCN produces AVP that entrains daily rhythms; limbic AVP cells exist in BNST/MeA (steroid-sensitive), positioning AVP to influence social, circadian, and stress circuits that bias approach vs avoidance (Young & Wang, 2004; Dumais & Veenema, 2016).

- Receptors - what AVP changes:

Table 1 Vasopressin receptors and motivational roles

| Receptor | Principal sites (central/peripheral) | Primary motivational functions | Key sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| V1aR | Lateral septum; amygdala; ventral pallidum/striatal pathways | Social salience, recognition, bonding; approach bias | Young & Wang, 2004; Dumais & Veenema, 2016; Bielsky et al., 2005 |

| V1bR | Anterior pituitary (corticotrophs); hippocampal CA2 | HPA potentiation (ACTH → glucocorticoids); stress–effort coupling; link to social memory | Tanoue et al., 2004; Hitti & Siegelbaum, 2014; DeVito et al., 2009 |

| V2R | Kidney collecting duct (peripheral) | Antidiuretic effects (not central to motivation) | Young & Wang, 2004 |

- V1aR (vasopressin V1a receptor) is widespread in forebrain (e.g., lateral septum, amygdala, ventral pallidum/striatal pathways) and mediates most central social/reward effects; V1bR is on pituitary corticotrophs and present at select limbic sites, linking AVP to stress energisation and social memory; V2R (vasopressin V2 receptor) is largely peripheral; AVP can also act at OXTR (oxytocin receptor), enabling AVP–oxytocin cross-talk (Young & Wang, 2004; Tanoue et al., 2004; Dumais & Veenema, 2016).

- Release modes - how broadly AVP acts: Beyond axonal terminal release, AVP is released from PVN/SON, allowing volume transmission that effects local networks and can support longer-lasting state changes. (Ludwig & Leng, 2006).

- Circadian gating - when motivation peaks: SCN AVP neurons help set the internal clock network’s period and coordinate downstream timing signals that gate arousal, effort, and social engagement across the day (Paul et al., 2023).

- Stress coupling - effort mobilisation: Parvocellular PVN neurons co-release CRH + AVP; AVP acting at V1bR potentiates ACTH, amplifying glucocorticoid output. V1bR-knockout mice show blunted ACTH/corticosterone at baseline and under stress - direct evidence that AVP is a co-driver of HPA activation (Tanoue et al., 2004).

- Integration nodes - where AVP biases approach/avoidance: The lateral septum (LS) functions as an integration hub connected with VTA/NAc reward pathways and receives dense vasopressinergic input from the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis and medial amygdala (BNST/MeA), which are steroid-sensitive social-behaviour nodes; classic tract-tracing in rats found little to no direct AVP projection from PVN/SON to LS (Young & Wang, 2004; Dumais & Veenema, 2016; De Vries & Buijs, 1983; Caffé, Van Leeuwen, & Luiten, 1987).

AVP and social behaviour

- Intro – what AVP changes in social motivation: In social contexts, central arginine vasopressin (AVP) adjusts which option feels salient and how much effort is invested - tilting behaviour toward approach (e.g., affiliation, caregiving) or avoidance/competition (e.g., vigilance, dominance). These effects are sex-sensitive, reflecting steroid regulation of AVP pathways (Rigney et al., 2022; Dumais & Veenema, 2016; Young & Wang, 2004).

- Circuit scaffold (who sends AVP where): Steroid-responsive AVP neurons in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) and medial amygdala (MeA) provide dense vasopressinergic input to the lateral septum (LS), a core node for social motivation; classic tract-tracing in rats identifies BNST/MeA - LS as the principal AVP route (De Vries & Buijs, 1983; Caffé et al., 1987; Dumais & Veenema, 2016). Hypothalamic AVP still influences LS-related behaviour indirectly - via PVN AVP co-driving HPA output (V1bR) and SCN AVP setting circadian phase - rather than as a major direct AVP afferent to LS in rodents (Tanoue et al., 2004; Paul et al., 2023; Young & Wang, 2004).

- Social recognition and salience (mechanism - behaviour): V1a receptors (V1aR) in LS are necessary and sufficient for normal social recognition in mice: septal V1aR blockade disrupts recognition on habituation–dishabituation tests, and LS-targeted V1aR re-expression rescues the deficit in V1aR-knockouts - evidence that LS AVP signalling assigns motivational value to familiar conspecifics (Bielsky et al., 2005).

- Affiliative bonding as social reward: In voles, elevated V1aR in ventral forebrain (ventral pallidum/LS) is critical for partner preference; viral overexpression of V1aR in these regions induces bonding in a normally non-monogamous species, indicating that AVP helps encode a partner as rewarding (Lim et al., 2004; Young & Wang, 2004).

- Hippocampal CA2/V1b and socio-cognitive memory: The CA2 subfield - rich in Avpr1b (V1bR) - is essential for social memory: silencing CA2 pyramidal neurons abolishes social recognition without broadly impairing other hippocampal memories. Concordantly, Avpr1b-knockout mice show deficits in social novelty/recognition and altered social motivation (Hitti & Siegelbaum, 2014; DeVito et al., 2009; Caldwell & Albers, 2016).

- Aggression/dominance are context-dependent: AVP within septal/extended-amygdala circuits can facilitate or inhibit aggression depending on species, sex, and situation (e.g., mating competition vs. territorial defence), showing that AVP’s social effects are conditional, not uniformly pro- or antisocial (Dumais & Veenema, 2016; Rigney et al., 2022).

- Sex differences (who is most affected, when): Males typically show greater AVP expression in BNST/MeA pathways and larger behavioural effects of V1a/V1b signalling; female effects are often state-dependent (e.g., estrous cycle, postpartum), consistent with steroid regulation of these circuits (Dumais & Veenema, 2016; Rigney et al., 2022).

- So what for motivation: In safe/familiar contexts, BNST/MeA-LS V1aR and CA2 V1bR signalling tends to heighten affiliative salience and persistence (e.g., bonding, caregiving). Under threat/competition, the same network can shift toward vigilance and defensive motivation - a peptide-driven, context-sensitive tuning of social effort (Young & Wang, 2004; Rigney et al., 2022; Dumais & Veenema, 2016).

AVP and reward pathways

- Intro - how AVP influences reward: Central arginine vasopressin (AVP) interfaces with mesolimbic reward circuits, altering both the value assigned to social options and the effort invested to pursue them; because V1a receptors (V1aR) in ventral forebrain nodes (lateral septum, ventral pallidum/striatal pathways) favour affiliative rewards while V1b receptors (V1bR) couple AVP to stress-hormone output, this receptor 'split' mechanistically explains why AVP promotes bonding/care in safe contexts but pushes vigilance/competition when stress is high (Dumais & Veenema, 2016; Rigney et al., 2022; Tanoue et al., 2004; Young & Wang, 2004).

- Where AVP meets dopamine (anatomy - function): The lateral septum (LS) is an integration hub that receives dense BNST/MeA - LS vasopressinergic input and connects to VTA/NAc dopamine pathways, allowing AVP arriving in LS to bias downstream dopaminergic computations toward approach (affiliation) or avoidance (vigilance) depending on context (Caffé et al., 1987; De Vries & Buijs, 1983; Rigney et al., 2022).

- Social bonding as a reward signal: In voles, elevating V1aR expression in ventral forebrain (ventral pallidum/LS) is sufficient to induce partner preference in a normally non-monogamous species, showing that AVP-V1aR signalling directly assigns reward value to a partner and drives approach behaviour (Lim et al., 2004; Young & Wang, 2004).

- Drug-reward normalisation (rodent CPP evidence): Microinjecting AVP into LS reduces amphetamine conditioned place preference and lowers nucleus accumbens dopamine, indicating that septal AVP down-weights non-social rewards and can tip choice toward adaptive social incentives (Gárate-Pérez et al., 2021).

- Stress-to-reward coupling (why context flips the effect): Paraventricular nucleus (PVN) AVP acting at pituitary V1bR potentiates ACTH and glucocorticoid release, energising the HPA axis; this stress drive feeds into reward circuits and tilts valuation away from affiliative rewards toward vigilance/competition when threat is salient - so the same peptide system that supports bonding in safety can bias defensive motivation under stress (Rigney et al., 2022; Tanoue et al., 2004).

- Sex differences in reward-related AVP effects: Because BNST/MeA AVP systems are steroid-sensitive and more prominent in males, AVP’s impact on reward valuation (e.g., pair-bond reward, dominance incentives) is often stronger in males, whereas female effects are more state-dependent (estrous/postpartum) - hence accurate predictions of AVP’s motivational effects must factor in sex and hormonal state (Dumais & Veenema, 2016; Rigney et al., 2022).

- So what for motivation: In affiliative/safe settings, V1aR-rich ventral forebrain circuits make social partners rewarding, promoting approach and sustained caregiving/affiliation; under threat or high stress, V1bR-mediated HPA activation reallocates motivational resources toward defensive or competitive goals - meaning AVP dynamically rebalances social vs. defensive motivation as a function of context and sex (Dumais & Veenema, 2016; Rigney et al., 2022; Tanoue et al., 2004; Young & Wang, 2004).

AVP and the stress response

- Intro - what AVP changes under stress: Central arginine vasopressin (AVP) coordinates the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis and limbic arousal/anxiety circuits, so it can shift motivation between persistence/effort and withdrawal/defence depending on the situation (Dumais & Veenema, 2016; Rigney, de Vries, Petrulis, & Young, 2022).

- HPA co-activation (mechanism - motivation): Parvocellular neurons in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) co-release corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and AVP into portal blood. AVP binds pituitary V1b receptors (V1bR) to potentiate adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), producing a larger glucocorticoid surge than CRH alone - i.e., a stronger internal 'mobilise effort' signal. V1bR-knockout mice show blunted ACTH/corticosterone at baseline and to acute stress, and selective V1b antagonists reduce stress-related behaviours in rodents, confirming AVP as a co-driver of HPA activation (Caldwell & Albers, 2016; Tanoue et al., 2004).

- Central anxiogenesis (where AVP raises avoidance): In limbic circuits - especially lateral septum and amygdala-connected pathways - higher AVP tone via V1a receptors (V1aR) is linked to increased anxiety/vigilance, whereas reducing septal V1aR is anxiolytic. Effects are typically stronger in males, consistent with steroid regulation of AVP pathways; functionally, this biases behaviour toward caution/avoidance when threat cues are present (Bielsky, Hu, Szegda, Westphal, & Young, 2005; Dumais & Veenema, 2016).

- Dendritic release sustains state changes: Besides classical axonal release, PVN/SON (supraoptic nucleus) magnocellular neurons can release AVP somatodendritically, creating volume transmission that modulates nearby stress circuits for minutes to hours - a mechanism for longer-lasting shifts in arousal and task persistence after stressors (Ludwig & Leng, 2006).

- Time-of-day gating of stress readiness: Suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) AVP provides circadian pacesetting that times when stress and arousal systems are most responsive, helping explain daily swings in effort readiness and stress-linked motivation (Paul et al., 2023).

- Plasticity to (social) stress: Chronic or social defeat/isolation stress alters AVP signalling across PVN and extended-amygdala pathways in species- and sex-specific ways (up or down regulation), recalibrating anxiety and social motivation and cautioning against one-size-fits-all predictions (Dumais & Veenema, 2016; Rigney et al., 2022).

- So what for motivation: By potentiating HPA output via V1bR and raising central vigilance via V1aR, AVP reallocates motivational resources; under moderate challenge it can sustain effort/persistence, whereas under high or prolonged threat it biases withdrawal/defensive action - with sex/hormonal state shaping the magnitude of these effects (Dumais & Veenema, 2016; Rigney et al., 2022; Tanoue et al., 2004).

AVP as the bridge between social, reward, and stress systems

- Intro – why AVP is a ‘bridge’: Central arginine vasopressin (AVP) coordinates social-behaviour, reward, and stress systems via three design features: (a) receptor topology - V1aR concentrated in ventral-forebrain social/reward nodes and V1bR in pituitary and hippocampal CA2; (b) non-synaptic (somatodendritic) release that prolongs signalling; and (c) circadian pacing from the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) that gates responsiveness across the day (Dumais & Veenema, 2016; Ludwig & Leng, 2006; Paul et al., 2023; Rigney, de Vries, Petrulis, & Young, 2022; Tanoue et al., 2004).

- Convergence hubs that blend signals: The lateral septum (LS) receives dense AVP input from the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) and medial amygdala (MeA) and is interconnected with ventral tegmental area (VTA) / nucleus accumbens (NAc) dopamine pathways, allowing AVP entering LS to bias dopaminergic computations about social cues (Caffé, Van Leeuwen, & Luiten, 1987; De Vries & Buijs, 1983; Rigney et al., 2022). The hippocampal CA2, enriched for V1bR, supplies social-memory signals to decision networks, linking identity/context to stress-responsive pathways (DeVito et al., 2009; Hitti & Siegelbaum, 2014).

- Social-value route (V1aR - approach): AVP acting at V1aR in LS/ventral forebrain assigns positive value to social partners: LS V1aR is necessary and sufficient for normal social recognition in mice, and increasing V1aR in ventral pallidum/LS is sufficient to induce partner preference in voles - demonstrating a direct route from AVP signalling to social reward (Bielsky, Hu, Szegda, Westphal, & Young, 2005; Lim, Wang, Olazábal, Ren, Terwilliger, & Young, 2004; Young & Wang, 2004).

- Stress–energy route (V1bR - HPA): Paraventricular nucleus (PVN) AVP acting at pituitary V1bR potentiates adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and the glucocorticoid surge - an endocrine “mobilise effortvasopressin signal; V1bR knockout blunts ACTH/corticosterone, confirming AVP as a co-driver of the HPA axis. Through CA2 V1bR, AVP also links sociocognitive memory to stress-relevant action selection (DeVito et al., 2009; Hitti & Siegelbaum, 2014; Tanoue et al., 2004).

- Competition and re-weighting of rewards: In the LS, AVP can down-weight non-social rewards: septal AVP microinjection reduces amphetamine conditioned place preference and lowers NAc dopamine, showing how AVP can shift priority away from drug incentives toward adaptive social goals (Gárate-Pérez et al., 2021).

- Timing and persistence of the bridge signal: Somatodendritic AVP release in PVN/SON supports minutes–hours of local modulation (state persistence), while SCN AVP sets time-of-day thresholds for arousal/effort - tuning when AVP will favour approach versus caution (Ludwig & Leng, 2006; Paul et al., 2023).

- So what for motivation: By delivering social-value signals (V1aR in LS/ventral forebrain), stress-energy signals (V1bR in HPA/CA2), and timing/persistence signals (SCN and dendritic release), AVP coordinates social, reward, and stress networks so behaviour shifts toward bonding/care in safe contexts and toward vigilance/defence under threat - modulated by sex and hormonal state (Dumais & Veenema, 2016; Rigney et al., 2022; Tanoue et al., 2004; Young & Wang, 2004).

Determinants and applications: sex differences, individual variation, human evidence

- Intro - what determines AVP’s motivational effects (and why this matters): Central arginine vasopressin (AVP) effects vary with who (sex, genotype), state (current stress load, hormones, circadian phase), and method (what is measured and how). These determinants explain when AVP amplifies affiliative/persistent effort versus vigilance/defence, and they guide cautious human application (Caldwell & Albers, 2016; Dumais & Veenema, 2016; Paul et al., 2023; Rigney, de Vries, Petrulis, & Young, 2022).

- Sex differences – where the larger effects come from (and when): Steroid-sensitive BNST/MeA - LS pathways are more prominent in males; accordingly, V1aR/V1bR manipulations often have bigger behavioural effects in males. In rodents, reducing septal V1aR is anxiolytic mainly in males; in humans, intranasal AVP changes social communication in a sex-specific manner - typically stronger in men (Dumais & Veenema, 2016; Rigney et al., 2022; Thompson, George, Walton, Orr, & Benson, 2006).

- Individual variation – AVPR1A genetics and social motivation: AVPR1A promoter (mediates the effects of vasopressin on cells) polymorphisms are associated with pair-bonding/relationship quality in men, consistent with natural differences in V1aR signalling mapping onto social motivational style (Walum et al., 2008).

- State variables – stress, hormones, and time of day: AVP’s impact flips with context. With high stress, V1bR-mediated HPA potentiation biases behaviour toward vigilance/defence; in low/safe contexts, V1aR-rich ventral-forebrain circuits favour affiliative valuation and persistence. SCN AVP sets time-of-day responsiveness, so the same challenge can evoke different motivation morning vs evening (Paul et al., 2023; Rigney et al., 2022; Tanoue et al., 2004).

- Methodological considerations – getting valid signals: Peripheral AVP measures poorly index central release; assay variability and small samples can obscure effects. Matching task valence to receptor route - V1aR (affiliation/recognition; LS/ventral forebrain) versus V1bR (stress–effort; pituitary/CA2) - improves interpretability and replication (Caldwell & Albers, 2016; Dumais & Veenema, 2016).

- Human evidence – what is most robust right now: (a) Sex-specific behavioural effects of intranasal AVP in controlled social tasks; (b) genetic links between AVPR1A variants and pair-bonding in men; and (c) review evidence that V1bR antagonism can reduce stress-related negative affect/alcohol use, though clinical effects remain mixed/modest (Caldwell & Albers, 2016; Thompson et al., 2006; Walum et al., 2008).

- Applications – practical take-aways: Expect larger AVP effects in males and when context matches circuit (V1aR - affiliation/recognition; V1bR - stress–effort). Use safe, cooperative contexts to engage V1aR-linked motivation and avoid threat cues that recruit V1bR/HPA when affiliation is desired. Pharmacologically, V1bR antagonists are plausible for stress-amplified motivation problems, but any use should be hypothesis-driven, sex-/state-stratified, and paired with behavioural strategies (Caldwell & Albers, 2016; Paul et al., 2023; Rigney et al., 2022; Tanoue et al., 2004).

Quiz

Conclusion

Central arginine vasopressin (AVP) biases motivation through three coordinated routes:

- Social-value signalling via V1aR in lateral septum/ventral-forebrain circuits

- Stress-energy mobilisation via V1bR and the HPA axis

- Timing/persistence via SCN circadian output and somatodendritic release.

Which route dominates depends on context (safety vs. threat), sex/hormones, current stress, and individual genetics (Caldwell & Albers, 2016; Dumais & Veenema, 2016; Ludwig & Leng, 2006; Paul et al., 2023; Rigney et al., 2022; Tanoue et al., 2004; Young & Wang, 2004).

- Mechanisms: AVP engages V1aR in LS/ventral pallidum to increase the salience of social options (and interface with dopamine reward networks) and V1bR in pituitary/CA2 to potentiate ACTH–glucocorticoid output and couple stress to effort; SCN AVP gates when these systems are most responsive, while dendritic release sustains state changes (Ludwig & Leng, 2006; Paul et al., 2023; Tanoue et al., 2004; Young & Wang, 2004).

- Contexts: In safe/affiliative settings AVP (V1aR) promotes approach, bonding and caregiving; under threat/competition V1bR–HPA signalling shifts behaviour toward vigilance/defence (Lim et al., 2004; Rigney et al., 2022; Young & Wang, 2004).

- Who/when: Effects are typically larger in males (steroid-sensitive BNST/MeA→LS pathways), vary with AVPR1A genotype, hormonal state and time of day, and show sex-specific behavioural responses to intranasal AVP in humans (Dumais & Veenema, 2016; Paul et al., 2023; Thompson et al., 2006; Walum et al., 2008).

Take-home applications:

- Build safe, cooperative contexts to engage V1aR-linked prosocial motivation (Lim et al., 2004; Young & Wang, 2004).

- Manage stress to prevent flips toward defensive/competitive motivation (Rigney et al., 2022; Tanoue et al., 2004).

- Time tasks to circadian windows of readiness (Paul et al., 2023).

- Pharmacology: V1bR antagonists are plausible for stress-amplified problems, but effects are mixed/modest—use sex-/state-stratified designs alongside behavioural strategies (Caldwell & Albers, 2016).

- Limitations & future. Peripheral AVP poorly indexes central release; prioritise circuit-matched tasks, adequate samples, and explicit tests of sex/circadian moderators in preregistered human studies (Caldwell & Albers, 2016; Dumais & Veenema, 2016).

See also

- Vasopressin (Wikipedia)

- Vasopressin and motivation (Book chapter, 2024)

References

Caffé, A. R., Leeuwen, van, & Luiten, M. (1987). Vasopressin cells in the medial amygdala of the rat project to the lateral septum and ventral hippocampus. The Journal of Comparative Neurology, 261(2), 237–252. https://doi.org/10.1002/cne.902610206

Caldwell, H. K., & Albers, H. E. (2015). Oxytocin, Vasopressin, and the Motivational Forces that Drive Social Behaviors. Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences, 51–103. https://doi.org/10.1007/7854_2015_390

Carter, C. S. (2017). The Oxytocin–Vasopressin Pathway in the Context of Love and Fear. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2017.00356

Das, A. (2005). Cortical Maps: Where Theory Meets Experiments. Neuron, 47(2), 168–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2005.07.004

Dash, M. B., Douglas, C. L., Vyazovskiy, V. V., Cirelli, C., & Tononi, G. (2009). Long-Term Homeostasis of Extracellular Glutamate in the Rat Cerebral Cortex across Sleep and Waking States. The Journal of Neuroscience, 29(3), 620–629. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.5486-08.2009

Dumais, K. M., & Veenema, A. H. (2015). Vasopressin and oxytocin receptor systems in the brain: Sex differences and sex-specific regulation of social behavior. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, 40, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yfrne.2015.04.003

Gárate‐Pérez, M. F., Méndez, A., Bahamondes, C., Sanhueza, C., Guzmán, F., Reyes‐Parada, M., Sotomayor‐Zárate, R., & Renard, G. M. (2019). Vasopressin in the lateral septum decreases conditioned place preference to amphetamine and nucleus accumbens dopamine release. Addiction Biology, 26(1). https://doi.org/10.1111/adb.12851

Hitti, F. L., & Siegelbaum, S. A. (2014). The hippocampal CA2 region is essential for social memory. Nature, 508(7494), 88–92. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13028

Lim, M. M., Wang, Z., Olazábal, D. E., Ren, X., Terwilliger, E. F., & Young, L. J. (2004). Enhanced partner preference in a promiscuous species by manipulating the expression of a single gene. Nature, 429(6993), 754–757. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02539

Ludwig, M., & Leng, G. (2006). Dendritic peptide release and peptide-dependent behaviours. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 7(2), 126–136. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn1845

Migliore, M., & Shepherd, G. M. (2005a). An integrated approach to classifying neuronal phenotypes. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 6(10), 810–818. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn1769

Rigney, N., de, J., Petrulis, A., & Young, L. J. (2022). Oxytocin, Vasopressin, and Social Behavior: From Neural Circuits to Clinical Opportunities. Endocrinology, 163(9). https://doi.org/10.1210/endocr/bqac111

Tanoue, A., Ito, S., Honda, K., Sayuri Oshikawa, Kitagawa, Y., Taka-aki Koshimizu, Mori, T., & Tsujimoto, G. (2004). The vasopressin V1b receptor critically regulates hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity under both stress and resting conditions. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 113(2), 302–309. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci19656

Tsuno, Y., Peng, Y., Horike, S., Wang, M., Matsui, A., Yamagata, K., Sugiyama, M., Nakamura, T. J., Daikoku, T., Maejima, T., & Mieda, M. (2023). In vivo recording of suprachiasmatic nucleus dynamics reveals a dominant role of arginine vasopressin neurons in circadian pacesetting. PLOS Biology, 21(8), e3002281. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3002281

Young, L. J., & Wang, Z. (2004). The neurobiology of pair bonding. Nature Neuroscience, 7(10), 1048–1054. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn1327

External links

- Hormones affect our physiology and behavior (BrainFacts - Society for Neuroscience)

- Oxytocin and vasopressin: Secrets of love and fear (Adam Lane Smith - blog)

- How can you tell if you're in love? (Medical News Today)