Motivation and emotion/Book/2025/Stockholm syndrome emotion

What are the emotional aspects of Stockholm syndrome?

Overview

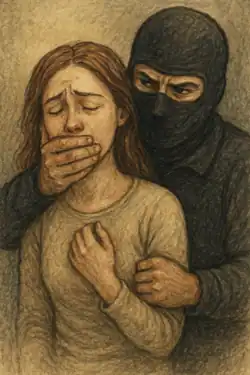

You have been kidnapped (see Figure 1). You feel lost and afraid for your life. You are thrown down the stairs to the basement of a horrible man's house. As you awake in an unfamiliar environment, day after day, you feel suffocated by the man's presence. The time feels as though it is standing still, and your movements feel automatic and out-of-body. As the days pass, you grow increasingly hungry, humiliated, and isolated from the real world. The man strips you of your regular thought patterns and defense mechanisms, as he manipulates you through love and hate. You don't feel like yourself anymore, and you don't recognise your own reflection. As you begin to further dissociate, you can't remember how you got into this position, nor can you recognize the evil-ness of the man. You begin to feel emotionally attached to this figure, as he seems to be the only one who appreciates you at all. Finally, as the day comes for you to escape, you don't feel as though you need it anymore. You have developed a relationship with the man of which you can't bear to break. This scenario is similar to what is felt by many kidnapping victims. Due to the psychological principles of instinct theory, attachment theory and the common emotional timeline, Stockholm syndrome has occurred to you. A response so deeply rooted in our instincts and genetics, you are just one of many that have survived.

|

Human motivation and emotion has been studied in many different ways over time to better understand way we act, think and feel.(Schater 2009). Having a better understanding of the driving forces behind your own behaviours, and the behaviours of others leads to many positive outcomes, including improved emotional regulation, better self-awareness, and stronger relationships with others (Schater, 2009). Instinct theory argues that motivation for all behaviour stems from humans having an innate drive to survive (Plutchik, 2001). It argues that all behaviours occur to satisfy fundamental survival needs such as hunger, thirst, and rest (Plutchik, 2001). Emotion is an adaptive response which has evolved to help humans respond quickly to environmental challenges and changes (Plutchik, 2001). Emotion guides our behaviour and keeps us out of dangerous situations (Plutchnik, 2001). For example, fear is often viewed as a negative emotion, of which is unproductive and only holds individuals back from success and self-actualisation (Plutchik, 2001). However, fear is a crucial emotion which triggers a person's instinctual fight or flight response, often saving them from potential harm (Plutchik 2001).

A humans need to belong is often underestimated and overlooked as one of the major survival instincts which drives behavior (Baumeister, 1995). The need to belong is a survival instinct deeply rooted in human evolution, as feeling accepted and supported by others increases an individuals chances of survival (Baumeister, 1995). The human brain often considers social rejection and isolation as equally as threatening as starvation or thirst, and understanding this fact is crucial to understanding the motives behind your own behaviors (Baumeister, 1995).

Kidnapping and hostage-taking involves the unlawful detention of a person, and victims of kidnapping/hostage taking experience heightened survival instincts (Alexander, 2009). This book chapter aims to explain the psychological science behind Stockholm Syndrome and emotion, to improve the motivational and emotional lives of individuals.

|

Focus questions

|

Stockholm syndrome and emotion

Stockholm syndrome is a complex psychological response to being kidnapped or held captive (Harnischmacher, 1987). It involves the victim developing positive feelings like empathy and loyalty toward their captor (Harnischmacher, 1987). It is most common in cases of hostage-taking, however, has also been observed in extreme cases of domestic violence (Ahmad et al., 2018). Ahmad & colleagues (2018) addressed the fact that Stockholm syndrome and partner violence is extremely under-investigated by conducting a meta-analysis. They aimed to determine the role of Stockholm syndrome between intimate partner violence and psychological distress (Ahmad et al., 2018). Results displayed that intimate partner violence resulted in victims rationalizing abuse due to distorted cognitions, a trait of Stockholm syndrome (Ahmad et al., 2018). This research is insightful, as it displays that Stockholm syndrome can occur to victims of high control in forms other than captor and captee (Ahmad et al., 2018). Studying and understanding the emotional aspects of Stockholm syndrome is crucial, as it explains to 'everyday' individuals how trauma and survival instincts can distort human relationships (Harnischmacher, 1987).

Origins

In the year 1973 a dramatic four-day bank robbery took place in Stockholm, Sweden, and there were four hostages taken (Logan, 2018). After five days captive, the victims presented as being supportive of their captors, and as though they were in alliance after the ordeal (Logan, 2018). After this event, Nils Bejerot coined the term "Stockholm syndrome", and defined it as the psychological tendency for a hostage to identify with their captor (Logan, 2018).

Instinct theory

Instinct theory is a concept which argues all behaviour occurs as a result of a humans innate drive to survive (Bandhu et al., 2024). According to instinct theory, humans are born with instincts which automatically assist in ensuring our survival (Bandhu et al., 2024). Common human instincts are seeking food when hungry, the fight or flight response in danger, and a tendency to seek social belonging (Bandhu et al., 2024). Instinct theory is extremely purposeful in research settings, as it often assists in explaining the motives behind bizarre and surprising behaviors across species (Harlow et al., 1965). Harry Harlow's (1965) monkey experiment is a classic example which proves how all species are born with an innate need to belong and feel cared for (Harlow et al., 1965). In this example, monkeys were given a choice between two surrogate 'mothers', one made of wire which provided milk, and one made of soft cloth, which was comforting but provided no milk (Harlow et al., 1965). When Harlow observed that majority of the monkey's preferred the soft clothed mother, over the feeding mother, it strengthened the argument that psychological needs are equally as important to survival than physiological needs (Harlow et al., 1965).

It is critical to note that survival instincts are significantly heightened in events which are considered disaster events (Alexander, 2018). Alexander (2018) explains that a kidnapping or hostage-taking scenarios can be considered as a 'disaster' event, and are far more complex to navigate as humans, then minor inconveniences or problems. He exclaims "Disasters have the potential to overwhelm the normal coping methods of individuals" (Alexander, 2018, p.12). Instinct theory and disaster events are crucial to understand, as they explain the motives behind the emotions present for someone who is experiencing Stockholm syndrome, or has experienced it in the past.

Attachment theory

Attachment theory is a psychological concept which aims to explain how humans form strong emotional bonds with their caregivers in the early years of development (Granqvist, 2021). The theory argues that the strength of the relationship a child has with its primary caregiver plays a crucial role in the child's ability to form future relationships (Granqvist, 2021). Bowlby and Ainsworth (1969) first researched attachment styles, and the four constructs of secure, anxious, avoidant, and disorganised are still accepted as accurate today.

Attachment theory plays a significant role to the emotional development of Stockholm syndrome, as similar to instinct theory, it explains why humans get attached to their captor in hostage situations (Granqvist, 2021). Being held in a hostage situation evokes a similar emotional response to what is experience through early childhood, the sensitive period where attachment tendencies develop (Teodora, 2025). When in a state of immense fear and vulnerability, a person's primary instinct is to seek safety by attaching themselves to the closest individual to them. In the case of kidnapping or hostage-taking, this often equals the kidnapper themselves (Teodora, 2025). Emotion plays a central role in attachment theory, as feelings of fear (see Figure 2), and dependency can lead the brain to associate the kidnapper with safety and protection, despite the abuse and trauma which they portray (Teodora, 2025). Instinct theory and attachment theory are just two explanations of the complex emotional processes which occur when being held captive.

Environmental conditions

There are specific environmental conditions which foster for the emotions which cause Stockholm syndrome (Alexander & Klein, 2009). Three which are specifically prominent are malnutrition, physical discomfort, and humiliation (Alexander & Klein, 2009). Malnutrition and constant hunger places the bodies nervous system under significant stress, as it elicits survival instincts (Alexander & Klein, 2009). This then leads to distorted cognitive processing and the individual turning to other behaviors to ensure their survival (Teodora, 2025). Physical discomfort fosters Stockholm syndrome, as it signals danger to the body, and elicits the fight or flight response (Alexander & Klein, 2009). On top of this, it causes a significant lack of rest (Alexander & Klein, 2009). Rest is what the body needs to survive, therefore a lack of rest, again places the bodies nervous system into a hyperactive state which distorts cognitive processing (Alexander & Klein, 2009).

Finally, feeling the emotion of humiliation causes the brain to consider it as a psychological attack on the dignity of the 'self' (Namnyak, 2008). Over a prolonged period of time, humiliation strips a person of their sense of self, instills shame and diminishes confidence, all factors which cause one's mental defenses to be weakened (Namnyak, 2008). Humiliation caused by the captor, leads to the captee viewing them as the only figure of which to seek social validation (Namnyak, 2008). This process is what then leads to the development of Stockholm syndrome (Namnyak, 2008).

Emotional concepts: a timeline

Stockholm syndrome occurs due to a complex interaction between emotions, instincts, and the victims environment. After scoping the literature on Stockholm syndrome, it was found there is a common timeline of emotions which are experienced by victims. Therefore, it is widely accepted that the concepts described in table 1, are essential to the development of Stockholm syndrome.

Table 1.

Key emotional concepts which researchers consider essential to the development of Stockholm syndrome.

| Emotional concept | Definition / example |

|---|---|

| Frozen fright | Frozen fright occurs due to an intense fear response, described as a "paralysis of the normal emotional reactivity of the body" (Alexander & Klein, 2009, p.18). This emotional experience is most likely to occur if the kidnapping process was extremely traumatic (Alexander & Klein, 2009). The bodies response to the trauma is delayed, as the subconscious mind is trying to keep the body and conscious mind safe. (Alexander & Klein, 2009) |

| Denial | Denial also occurs due to intense fear and anger (Alexander & Klein, 2009). Victims often subconsciously deny that the kidnapping event even occurred, as a coping mechanism for the abuse and trauma (Alexander & Klein, 2009). |

| Disassociation | Disassociation is another coping mechanism of extreme abuse and trauma, as it involves the victim completely and subconsciously disassociating from their own body (Shim et al., 2024). When threats become too intense for the bodies automatic coping mechanisms, the next step is for the mind to disassociate from its own sense of self (Shim et al., 2024). |

| Psychological infantilism | Psychological infantilism is a regressed behavior which involves the victim subconsciously returning to a child-like state, where they are excessively clingy and dependent to their captor (Alexander & Klein, 2009). As another way of coping with extreme stress, this emotional state forces the victim to become completely complient to the captor, similar to a parent-child relationship (Alexander & Klein, 2009). |

| Emotional bond | An emotional bond between captor and captee is formed as a result of the above emotional experiences felt by the victim (Logan, 2018). However, the bond is formed as a result of trauma (Logan, 2018). Trauma bonding occurs due to the complex cycle of abuse and fear, paired with dependency and intermittent kindness (Logan, 2018). |

Test yourself

|

Applications

Everyday individuals can still apply the principles related to Stockholm syndrome and emotion to their own motivational and emotional lives, even if they have never experienced kidnapping or hostage taking first-hand. Instinct theory is the first psychological concept which can be applied, because understanding and acknowledging the motives behind one's emotions in stressful situations, they are better able to cognitively process their surroundings (Bandhu et al., 2024). On top of this, instinct theory highlights how it is crucial to trust your instincts, as doing this will keep you from danger (Bandhu et al., 2024). Understanding attachment theory is also crucial, as it explains the impact of early relationships in your life, on your ability to form relationships in the future (Fearon & Roisman, 2017). As the theory poses several attachment styles, this provides explanations as to how and why you manage your emotions as you do (Fearon & Roisman, 2017).

Learned helplessness

Learned helplessness is a psychological state in which the individual feels as though they have no control over the situation they are in, or what happens to them (Hammock et al., 2012). It is a common result for victims who withstand extended periods of captivity (Hammock et al, 2012). Learned helplessness is a practical application to the theories of Stockholm syndrome, as it is an alternate reaction to being held captive, with no real positive outcomes (Hammock et al., 2012). It is considered a survival mechanism, as accepting and surrendering to one's circumstances decreases the bodies response to the threat, and the fight or flight response is weakened (Hammock et al., 2012). Learned helplessness is not only observed in hostage taking situations, but also in the workplace, toxic romantic relationships, and educational settings (Hammock et al., 2012). Understanding the behavioral traits of someone experiencing learned helplessness in the real-world is crucial as you can step-in and help their situation (Hammock et al., 2012).

The adult brain vs the child's brain

Research into the neuropsychological mechanisms of Stockholm syndrome and emotion, has led to a better understanding of the differences between how the adult brain responds to stress versus the child's brain. Due to ethical concerns when children are involved, follow-up studies on specific cases are limited (Alexander & Klein, 2009). Therefore, the double case study analysis below compares and contrasts two examples of more high-profile Stockholm syndrome cases; Natascha Kampusch and Brian Keenan.

|

Double case study analysis

"At that precise moment a young, pale, frightened women, her skin ghostly white after years of being kept away from natural light, her eyes squinting and watery from the sunshine that she was so unnused to, made a run from the driveway (see Figure 3) of No.60 Heinestrasse." (Hall and Leidig, 2006, foreword) Natascha Kampusch was ten years old when she was kidnapped on her way to school. She was held captive in the cellar of "a predator of the sort that hollywood scriptwriters and imaginative novelists invent to represent evil incarnate" (Hall and Leidig, 2006, forword). After 8 years, she escaped. She denies the development of stockholm syndrome, however many of her symptoms reveal that aspects of it did develop (Hall and Leidig, 2006). Natascha Kampusch's story highlights the complex ways in which a child's brain responds to trauma (Hall and Leidig, 2006). As she adapted to her new environment extremely quickly, this shows that neuroplasticity, and adaption is strongest in childhood (Hall and Leidig, 2006). Adults are more likely to resist as their neural pathways and preferences are already formed (Hall and Leidig, 2006). Brian Keenan was abducted and held at gunpoint by Islamic militants (Keenan, 1990). Over the next 1,574 days, Keenan was "stripped of every human freedom, every choice, every element of identity" (Keenan, 1990, forword). However, where Keenan's story differs from Natascha's is that he was not alone in captivity (Keenan, 1990). Keenan forged a special emotional bond with fellow hostage John Mccarthy describing him as "more than a friend. [John] was my sanity" (Keenan, 1990, forward). Keenans strong emotional bond with fellow hostage John could be an explanation as to why neither of them developed Stockholm syndrome (Keenan, 1990). The key insight these case studies provide, is they explain the emotional differences between a child and an adult. For a child as young as 10, their identity is still forming, therefore being held captive becomes a part of their personal development (Hall and Leidig, 2006). However, for someone in their 30's, they already have a strong sense of self and a pre-existing identity (Keenan, 1990). Therefore, they are more resistant to the indoctrination process of being held captive (Keenan, 1990). Natascha Kampusch's story highlights how children are more likely to emotionally suppress and de-associate from the trauma (Hall and Leidig, 2006), however Brian Keenans displays how developed brains possess greater self-awareness to process fear and anger (Keenan, 1990). |

Critiques

Many studies argue that post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a more common response to being held-hostage, than Stockholm syndrome. For example, Favaro and colleagues (2000) conducted a study aiming to investigate the effects of being kidnapped for ransom. After analysing the health status of kidnapping victims, results showed that PTSD was significantly more common than Stockholm syndrome. With this in mind, future research should aim to analyse what differentiates someone from developing PTSD instead of Stockholm syndrome

Secondly, Bailey & colleagues (2023) argue that there is significantly scarce empirical research supporting the assertion that a 'positive bond' is formed as a result to the trauma of being kidnapped. They argue that the term 'appeasement' should be used instead of Stockholm syndrome, to describe how survivors are emotionally attached to their captors (Bailey et al., 2023). They propose this in the hopes it will "provide a science-based explanation for their stories of survival" (Bailey et al., 2023, p.3)

Conclusion

Stockholm syndrome is a complex and subconscious coping strategy which is observed in victims of kidnapping or hostage taking situations (Harnischmacher, 1987). It involves victims experiencing positive emotions toward their capture (Harnischmacher, 1987). Stockholm syndrome can be explained by instinct theory, which argues humans have an innate drive to survive and all behavior is a reflection of this drive (Bandhu et al., 2024). It is also partially explained by attachment theory in that all humans have an innate need to belong, therefore cling to any 'caregiving' figure in their environment (Granqvist, 2021). The emotional concepts of Stockholm syndrome often occur in sequence, and reflect the instincts felt by the individual (Alexander & Klein, 2009). These concepts include frozen fright, denial, disassociation, psychological infantilism, and emotionally bonding. The research done into Stockholm syndrome and emotion has many applications in real-world settings. Firstly, individuals are better able to cognitively process their surroundings, coping mechanisms, and understand the motives behind their relationships (Bandhu et al., 2024). Secondly, Stockholm syndrome has led to developments in the field of learned helplessness, and finally, it has explained many differences between the child's brain and the adult brain (Hammock et al., 2012). It is important to keep in mind, many researchers disagree Stockholm syndrome as a concept, with one arguing PTSD is a more common response, and another advocating to change the term used all together (Bailey et al., 2023). Regular individuals can and should strive to understand the psychological theorem rooted in Stockholm syndrome and emotion, to improve their own motivational and emotional lives.

See also

- Attachment theories (Wikipedia)

- Motivation and emotion (Book chapter, 2025)

- Trauma bonding (Wikipedia)

References

Alexander, D. A. (2005). Early mental health intervention after disasters. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 11(1), 12-18. https://doi.org/10.1192/apt.11.1.12

Alexander, D. A., & Klein, S. (2009). Kidnapping and hostage-taking: a review of effects, coping and resilience. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 102(1), 16–21. https://doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.2008.080347

Bailey, R., Dugard, J., Smith, S. F., & Porges, S. W. (2023). Appeasement: replacing Stockholm syndrome as a definition of a survival strategy. European journal of psychotraumatology, 14(1), 2161038. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008066.2022.2161038

Bandhu, D., Mohan, M. M., Nittala, N. A. P., Jadhav, P., Bhadauria, A., & Saxena, K. K. (2024). Theories of motivation: A comprehensive analysis of human behavior drivers. Acta Psychologica, 244, 104177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2024.104177

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (2017). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Interpersonal development, p.57-89.

Bowlby, J., Ainsworth, M., & Bretherton, I. (1992). The origins of attachment theory. Developmental Psychology, 28(5), 759-775.

Favaro, A., Degortes, D., Colombo, G., & Santonastaso, P. (2000). The effects of trauma among kidnap victims in Sardinia, Italy. Psychological Medicine, 30(4), 975-980. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291799001877

Fearon, R. P., & Roisman, G. I. (2017). Attachment theory: progress and future directions. Current opinion in psychology, 15, 131-136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.03.002

Granqvist, P., & Duschinsky, R. (2021). Attachment theory and research. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.013.51

Hall, A., & Leidig, M. (2015). Girl in the Cellar-The Natascha Kampusch Story. Hachette UK.

Hammack, S. E., Cooper, M. A., & Lezak, K. R. (2012). Overlapping neurobiology of learned helplessness and conditioned defeat: Implications for PTSD and mood disorders. Neuropharmacology, 62(2), 565–575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.02.024

Harlow, H. F., Dodsworth, R. O., & Harlow, M. K. (1965). Total social isolation in monkeys. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 54(1), 90-97. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.54.1.90

Harnischmacher, R., & Müther, J. (1987). The Stockholm syndrome. On the psychological reaction of hostages and hostage-takers. Archiv fur Kriminologie, 180(1-2), 1-12.

Inić, T. (2025). Stockholm syndrome: A dimension of trauma. Sanamed, 20(1). https://doi.org/10.5937/sanamed0-57254

Keenan, B. (1993). An evil cradling. Random House.

Logan, M. H. (2018). Stockholm syndrome: Held hostage by the one you love. Violence and gender, 5(2), 67-69. https://doi.org/10.1089/vio.2017.0076

Namnyak, M., Tufton, N., Szekely, R., Toal, M., Worboys, S., & Sampson, E. L. (2008). ‘Stockholm syndrome’: psychiatric diagnosis or urban myth?. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 117(1), 4-11. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01112.x

Plutchik, R. (2001). The nature of emotions: Human emotions have deep evolutionary roots, a fact that may explain their complexity and provide tools for clinical practice. American scientist, 89(4), 344-350. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27857503

Shim, S., Kim, D., & Kim, E. (2024). Dissociation as a mediator of interpersonal trauma and depression: adulthood versus childhood interpersonal traumas3. BMC psychiatry, 24(1), 764. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-024-06095-2

External links

- Effective treatment options for Stockholm syndrome (psywellpath.com)

- What is Stockholm syndrome (youTube)