Motivation and emotion/Book/2025/Polyvagal theory

What is polyvagal theory, how does it explain the relationship between the autonomic nervous system and emotion regulation, and what are its applications?

Overview

.jpeg)

You are walking alone at night and suddenly hear footsteps closing in behind you. Your heartrate jumps, you can feel your muscles tense and your breathing becomes quick and shallow.

Your nervous system has just shifted gears to "protection mode". Your muscles are primed for action and you are prepared to fight or flee.

|

If you have ever taken an introductory psychology course or perused around on stress management related websites or blogs, it is likely that you will have encountered some adaptation of the autonomic nervous system model. According to this model, arousal is regulated by two systems within the autonomic nervous system: the sympathetic system, and the parasympathetic system. These two systems are responsible for producing the well known "fight or flight" response by increasing arousal, and the lesser known "rest and digest response" by decreasing arousal (Waxenbaum et al., 2023).

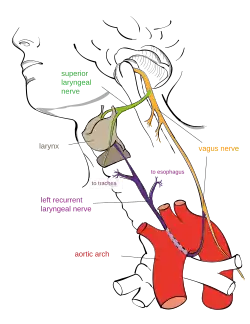

In 1994 a new, more detailed framework of the autonomic nervous system was proposed, which expanded massively on the traditional model described above. This new framework was fittingly called the Polyvagal theory, taking its name from the vagus nerve on which it focuses. At its core, Polyvagal theory emphasises the role of the Vagus nerve in regulating autonomic nervous system processes. The Polyvagal model of the autonomic nervous system, contrary to the traditional model, suggests that within the parasympathetic system exist two functionally distinct subdivisions: the ventral vagal system, and the dorsal vagal system, which are responsible for coordinating our responses to cues of safety and threat (Porges, 2025). Polyvagal theory suggests that the autonomic nervous system's function transcends beyond simply regulating arousal levels, and rather, is central to supporting social engagement, emotional resilience and adaptive physiological responses (Porges, 2025).

You turn around to assess the situation, and realise that the footsteps belong to a close, trusted friend who is trying to catch up with you. You feel a wave of relief as your muscles relax, your breathing slows and you begin to feel safe again.

According to Polyvagal theory, your nervous system has now shifted gears away from "protection mode" and into "connection mode". You are safe and ready to rest, relax and importantly, to socialise.

|

Many core concepts proposed in Polyvagal theory, including neuroception, dissolution, and co-regulation are suggested to have extremely important implications in both understanding and developing strategies to enhance emotional regulation. Although polyvagal theory has faced a great deal of criticism since its original development, particularly regarding its physiological and evolutionary bases, application of its theoretical principles has been shown to be effective in both clinical and non-clinical settings.

Overall, polyvagal theory provides a detailed framework for the function of the autonomic system and its effect on emotionality that, although currently mostly scientifically unsupported, may have useful practical applications.

|

Focus questions 1. What is polyvagal theory? 2. What is the proposed relationship between the autonomic nervous system and emotional regulation? 3. What are the theory's limitations? 4. What are the clinical applications of polyvagal theory?

|

What is Polyvagal theory

Polyvagal theory, originally developed in 1994 by Dr. Stephen Porges, focuses on the function of the Vagus nerve in regulating the autonomic nervous system, with particular emphasis being placed on its regulation of the parasympathetic nervous system. The theory emphasises the role of socialisation in maintaining human wellbeing, claiming that our ability to socially connect with one another is a result of the healthy functioning of our autonomic nervous system. Porges describes sociality as "a mechanism to regulate and optimize physiological state and homeostatic processes" (Porges, 2021). Essentially, this suggests that socialisation can be used as a tool to maintain feelings of safety and calmness even in unfamiliar or scary situations. Ultimately, the theory is targeted at providing a neurophysiological framework for understanding how the human autonomic nervous system functions and, importantly, how socialisation, emotional resilience and adaptive physiological responses are influenced by this.

In order to wholly understand polyvagal theory, it is important to first understand the concept of arousal as well as the more widely used traditional model of the autonomic nervous system, which polyvagal theory expands on. Briefly, the term "arousal" is used in psychology to describe any form of excitation or activation of the brain (Reid et al., 2025). Prior to the development of Polyvagal theory, the traditional model of the autonomic nervous system suggested that arousal is regulated by two structurally and functionally distinct systems within the autonomic nervous system: the sympathetic system and the parasympathetic system (Lopez Blanco & Tyler, 2025; Waxenbaum et al., 2023). The sympathetic system is proposed to increase arousal, preparing us for action, and the parasympathetic system is thought to decrease arousal, essentially, returning us to a state of calmness in which our bodies can relax, and rejuvenate (Lopez Blanco & Tyler, 2025).

The ventral and dorsal vagal systems

Polyvagal theory expands on this model by suggesting that the parasympathetic system can be split into two further subdivisions: the ventral vagal system, and the dorsal vagal system.

The ventral vagal system is, in many ways, reflective of the traditionally proposed function of the parasympathetic system. Physiologically, it is responsible for slowing heartrate and breathing, and returning the body to the "rest and digest" state following a period of high arousal (Poli et al., 2021; Porges, 2021). It is additionally thought to be vital in facilitating social connection and emotional regulation, which is essential for maintaining overall wellbeing (Porges, 2021). Porges suggests that the Ventral vagal system is activated as a response to detecting safety, allowing us to focus our cognitive and physiological resources on relaxation, rejuvenation, learning, and importantly, connection (Porges, 2025).

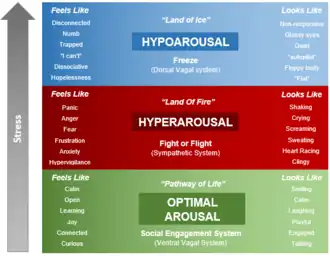

The dorsal vagal system facilitates what Porges describes as our most primitive defense mechanism: the freeze response (Grossman, 2023; Porges, 2025). This response, which is also often referred to as immobilisation or dorsal vagal shutdown, is described in the literature to be a last resort safety mechanism that we are biologically programmed to rely on when overwhelmed or in extreme danger (Porges, 2021). An important distinction is made here between threats that we believe we have the capacity to overcome and threats that we feel powerless against. Like the traditional autonomic system model, Polyvagal theory recognises the role of the sympathetic system in responding to threats, however it is argued that this system is only activated upon encountering manageable threats that we believe we can overcome with the fight or flight response (Grossman, 2023; Porges, 2025). When facing a threat so overwhelming that the sympathetic fight or flight response appears futile, the sympathetic system is, in a way, overriden by the dorsal vagal system, activating the primitive "freeze" response as a last resort survival strategy (Grossman, 2023). Physiologically, this results in a massive slowing of the heartrate and disrupted, uneven breathing, whilst also inducing emotional and social shut-down as well as dissociation (Porges, 2021). This process of freezing is proposed to be the same process that is responsible for less evolved vertebrates "playing dead" when faced with overwhelming threats (Grossman, 2023).

Evolutionary origins

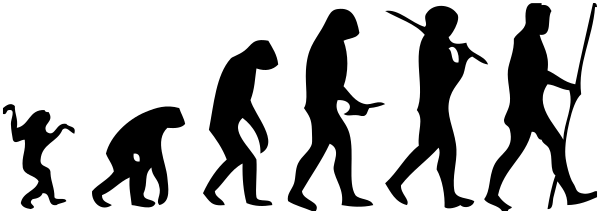

At its core, Polyvagal theory is an evolutionary perspective, arguing that the human autonomic nervous system has evolved specifically to support social engagement and emotional co-regulation, which are both critical to humanity's collective survival (Porges, 2021). The ventral vagal system, being responsible for sociality in humans, is suggested to have been evolutionarily repurposed from ancient brainstem circuits that are unique to mammals (Porges, 2025). Porges suggests that in ancestral vertebrates from which we evolved, the ventral vagal system did not exist. Rather, cardioinhibitory vagal fibers, which are responsible for releasing neurotransmitters to decrease heartrate, are located primarily in the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve.

Polyvagal theory proposes that at some point during evolution, these cardioinhibitory fibers migrated ventrally (upward) from the dorsal motor nucleus and accumulated in the nucleus ambiguus (Porges, 2023; Porges, 2025). This created a myelinated pathway within the vagus nerve that is capable of supporting the complex interaction between socialisation and safety, this pathway being the ventral vagal system (Porges, 2023).

With the evolution of the ventral vagal system, the human nervous system was functionally altered to prioritise socialisation and emotional coregulation, which are both known to be important in maintaining wellbeing. This change essentially shifted the purpose of the parasympathetic system from a more primitive defense mechanism to an evolved tool for sociality and self-soothing (Haeyen, 2024).

Filling the gaps: Neuroception and Dissolution

The mechanisms by which we assess and respond to threats according to Polyvagal theory can be explained by two processes: neuroception and dissolution.

Neuroception can be defined simply as the autonomic nervous system's automatic safety detector (Porges, 2025). The term neuroception describes the process by which we automatically and unconsciously assess our environment and viscera for cues of danger. Porges emphasises that this process is not cognitively informed; we do not rationalise cues of safety, and we are not consciously aware of this process occurring. It has additionally been suggested that humans are uniquely capable of informing their neuroception based on social cues (Porges, 2023).

| For example,

If you were to walk through a thorn bush, your automatic assessment of how safe you are (neuroception) would be informed by: Environmental cues: What you see (sharp thorns surrounding you) Visceral cues: What you feel (pain) Social cues: How others react (a bystander grimaces) |

Following neuroception, our nervous system must prepare us to respond accordingly to any potential threats. This is where the process of neuroception ends and the process of dissolution begins. The term dissolution can be defined simply as evolution in reverse. In the context of our nervous system, it describes how we shift from utilising more evolved processes to less evolved processes as stress increases (Haeyen, 2024; Nicolaou, 2022).

As previously established, the ventral vagal system is thought to be the most highly evolved structure in our autonomic nervous system, and the dorsal vagal system, the most primitive. This allows us to organise our three different response systems hierarchically (see table 1).

Table 1

Hierarchical response levels

| Hierarchical order | Threat level | System activated | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Connection | Highest | Safe/No threat | Ventral vagal |

| Mobilisation | Mid-level | Moderate threat | Sympathetic |

| Immobilisation | Lowest | Overwhelming threat | Dorsal vagal |

Polyvagal theory argues that within this hierarchy, when arousal is low, higher level systems inhibit lower level systems. This means that without the presence of stress, the ventral vagal system essentially blocks the sympathetic system and dorsal vagal system from functioning, preventing physiological stress responses (Nicolaou, 2022; Porges, 2025). As arousal increases, however, the ventral vagal system, which is activated by cues of safety, no longer functions. As activity of the ventral vagal system decreases, the lower level systems are no longer inhibited, and thus, their activity rises (Porges, 2021). Further, the sympathetic system is said to inhibit the dorsal vagal system until arousal becomes so heightened that the sympathetic system is no longer able to process it, and essentially shuts down (Porges, 2021). In this way, our response to arousal is thought to 'devolve' as arousal increases.

|

Section Review: What is polyvagal theory?

|

Polyvagal theory and emotional regulation

Emotional regulation can be defined as the process of examining, appraising and adapting the intensity of emotional reactions, particularly when responding to highly arousing situations (Balter et al., 2025). In short, the term describes our ability to remain relatively in control of our emotions in spite of extreme stress, excitement, or shock.

Origins of emotion

In understanding emotional regulation from a Polyvagal perspective, it is necessary to first consider how emotions originate. Emotions are proposed to form as a result of one of two processes: bottom-up perceptual experience or top-down conceptual experience (Balter et al., 2025).

Perceptual generations of emotion are automatic and unconscious, and form as immediate reactions to the environment, where conceptual generations of emotion occur as a result of conscious cognitive understanding of the environment.

| For example:

If you saw a spider on your desk your immediate perceptually generated emotion may be fear If you then investigated the spider and discovered that it was fake, you could cognitively assess the threat that the fake spider poses and conceptually generate a feeling of relief |

Perceptual generations of emotion are particularly useful for understanding the polyvagal perspective as they are proposed to be a direct result of neuroception.

Polyvagal emotional regulation

Polyvagal theory offers a unique framework on how the autonomic nervous system can impact our emotions and how cues of threat and safety influence our subsequent responses to these emotions (Balter et al., 2025).

As aforementioned, the process of neuroception is thought to unconsciously produce emotion, which implies that our emotions are informed by our perception of safety. Thus, when an individual feels safe, they are likely to experience emotions associated with the ventral vagal system such as calmness, joy, or curiosty. Likewise, when an individual feels unsafe, they are likely to experience either sympathetic emotions such as anger and fear, or, emotions associated with dorsal-vagal shutdown such as helplessness or depression (Balter et al., 2025; Manzotti et al., 2023).

When an individual's neuroception is particularly biased toward interpreting cues as threatening, Polyvagal theory argues that their capacity for calm, social connection and self-regulation is inherently limited. This leaves them prone to experiencing more distressing emotions in day to day living (Porges, 2025).

Polyvagal theory, therefore, argues that explicit cues of safety are essential for positive emotionality in humans. This is where the evolutionary role of the ventral vagal system as a facilitator for sociality becomes particularly important. As aforementioned, humans have a unique capacity to incorporate social cues of safety into their neuroception (Manzotti et al., 2023; Porges, 2025), allowing us to engage in a process called co-regulation. Co-regulation refers to the process by which positive interpersonal interactions produce cues of safety, promoting positive emotionality and emotional regulation capacity as a result. Essentially, this process describes how positive social support tends to make us happier and more calm, whilst also strengthening our capacity for emotional regulation (Balter et al., 2025).

It is important to emphasise that although co-regulation can be a powerful tool for promoting emotional regulation, it can only occur as a result of positive social interaction when cues of safety are present. Hostile or otherwise negative social interactions are likely to produce cues of threat, which may disable the ventral vagal system entirely, eliminating the individual's capacity for co-regulation altogether and potentially leading to sympathetic emotional responses as a defensive measure (Balter et al., 2025).

|

Section Review: Polyvagal theory and emotional regulation

|

Applications of Polyvagal theory

Polyvagal theory provides a detailed framework for understanding the interplay between the nervous system, feelings of safety and emotional outcomes. The theory has various clinical applications, however, substantial existing critique of the theory should be considered in such application. Whilst it may be a useful theoretical framework, many of the ideas in polyvagal theory are not proven and thus application of the theory is not guaranteed to be effective.

Clinical Applications

In the context of psychotherapy, polyvagal theory can be used as a framework for understanding how physiological states and particularly, how persistent stress can influence emotionality and emotional regulation. It is argued that individuals who experience more negative affect such as those with depression or anxiety tend to be biased toward interpreting environmental cues as threatening, which ultimately leads to persistent sympathetic activation or dorsal vagal shutdown (Porges, 2025). To combat this, the polyvagal approach to psychotherapy ultimately aims to alter clients' neuroception biases from reactionary and defensive to optimistic and prosocial (Haeyen, 2024). This is particularly useful when dealing with cases involving trauma, as Porges argues that traumatic experiences are extremely likely to lead to neuroception biases.

In order to effectively alter neuroception biases, Porges argues that autonomic flexibility must be restored, and vagal pathways must be strengthened through consistent use. Currently, a variety of polyvagal-informed care strategies are proposed to recalibrate neuroception (see table 2).

Table 2

Polyvagal-informed care strategies

| Intervention | Mechanism | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Sonic augmentation technology | Acoustic modulation that mimics the natural rythms of the nervous system | Supports emotional co-regulation, restores visceral homeostasis |

| Safe and Sound protocol (SSP) | Auditory stimulation activates ventral vagal system through pathways originating in the ear | promotes social engagement readiness, shifts neuroception toward safety |

| Breath/rhythm based practices | Stimulates ventral vagal system, alters physiological response to increase visceral safety cues | Builds regulation skills, promotes interoceptive awareness |

| HRV biofeedback training | Uses real-time feedback on RSA and heart rate to train awareness of vagal tones/shifts | Increases awareness and self-regulatory capacity |

Note. Adapted from "Polyvagal Theory: Current Status, Clinical Applications, and Future Directions," by S. W. Porges, 2025, Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 22(3), 169. https://doi.org/10.36131/cnfioritieditore20250301

Polyvagal-informed care strategies can be used in conjunction with a variety of different psychotherapy approaches. Although these strategies are compatible with most modalities of therapy, they are reported to be most commonly used alongside creative arts and psychomotor therapies (Haeyen, 2024; Penzes et al., 2025).

Common critiques and limitations

Although the theoretical framework behind polyvagal theory is well reasoned, critics of polyvagal theory consistently note a lack of empirical evidence to support many of the theory's claims (Grossman, 2023; Roffey, 2025).

Particularly notable is the lack of evidence in support of Porges' key neurophysiological claim that the ventral vagus nerve is more evolutionarily advanced and "newer" than the dorsal vagus nerve. This claim has actively and consistently been disproven by neuropsychological research, with research over 45 years ago to date indicating that functionally distinct systems do not exist within the vagal nerve, and additionally, vagal control of the heartrate is mediated entirely by the nucleus Ambiguus, with no active neurons being present in the dorsal vagal motor nucleus (Grossman, 2023).

Further critique of the theory targets its primary evolutionary claims. Polyvagal theory posits that the nucleus Ambiguus, otherwise known as the ventral vagal complex is unique to mammalian evolution. This claim was disproven after a paper by Monteiro et al. (2018) discovered vagus nerve fibres leading from the nucleus Ambiguus to the heart in the very non-mammalian lungfish. Another more recent review additionally highlighted that many vertebrate species experience respiratory sinus arrhythmia, a process that is regulated by the nucleus Ambiguus, indicating that the structure is in fact present in less evolved non-mammals (Taylor et al., 2022).

Finally some critics suggest that polyvagal theory, in its entirety, lacks falsifiability, essentially rendering it scientifically invalid (Grossman, 2023; Roffey, 2025). Porges, however, disputes this claim, stating that the theory has generated a variety of testable hypotheses, which have been tested, supported, and in some cases, disproven across various domains in psychological and physiological research (Porges, 2025).

Although many criticisms of polyvagal theory persist, Porges still continues to refine his theory in light of new evidence (Porges, 2025), and emphasises the proven practical effectivity of the theory when applied clinically.

Overall, the scientific basis of polyvagal theory is still heavily contested to date, however, despite lacking physiological evidence, a significant body of evidence does exist supporting the effectiveness of polyvagal-informed treatment (Bailey et al., 2020; Balter et al., 2025; Haeyen, 2024).

|

Section Review: Common critiques and limitations

|

Conclusion

In summary, Polyvagal theory provides a useful and in depth framework for understanding the autonomic nervous system and its role in emotional regulation processes. It provides detailed insight into how cues of safety and threat can influence emotional responses and additionally informs means by which emotional regulation can be improved in individuals. Polyvagal theory has a variety of empirically supported clinical applications, however many points of critique still exist within the theory.

See also

- Window of tolerance (Book chapter, 2022)

- Polyvagal theory (Wikipedia)

References

Balter, A. S., Bertrand, J., & Katz, E. (2025). “Once upon a time there was an autonomic response”: Developing a Praxis for Integrating Polyvagal Theory into Early Childhood Education to Improve Children’s Emotion Regulation. Social and Emotional Learning: Research, Practice, and Policy, 100127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sel.2025.100127

Grossman, P. (2023). Fundamental challenges and likely refutations of the five basic premises of the polyvagal theory. Biological Psychology, 180, 108589. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2023.108589

Haeyen, S. (2024). A theoretical exploration of polyvagal theory in creative arts and psychomotor therapies for emotion regulation in stress and trauma. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1382007. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1382007

Lopez Blanco, C., & Tyler, W. J. (2025). The vagus nerve: a cornerstone for mental health and performance optimization in recreation and elite sports. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1639866. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1639866

Manzotti, A., Panisi, C., Pivotto, M., Vinciguerra, F., Benedet, M., Brazzoli, F., ... & Chiera, M. (2024). An in‐depth analysis of the polyvagal theory in light of current findings in neuroscience and clinical research. Developmental psychobiology, 66(2), e22450. https://doi.org/10.1002/dev.22450

Monteiro, D. A., Taylor, E. W., Sartori, M. R., Cruz, A. L., Rantin, F. T., & Leite, C. A. (2018). Cardiorespiratory interactions previously identified as mammalian are present in the primitive lungfish. Science advances, 4(2), eaaq0800. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aaq0800

Nicolaou, D. (2022). The Polyvagal Theory in our understanding of safety and danger: How our body holds on to our experiences.

Pénzes, I., Abbing, A., & de Witte, M. (2025). How to use theories to explain effects of the creative arts therapies: The case of Polyvagal Theory. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 95(10231), 6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2025.102316

Poli, A., Gemignani, A., Soldani, F., & Miccoli, M. (2021). A systematic review of a polyvagal perspective on embodied contemplative practices as promoters of cardiorespiratory coupling and traumatic stress recovery for PTSD and OCD: research methodologies and state of the art. International Journal of environmental research and public health, 18(22), 11778. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182211778

Porges, S. W. (2021). Polyvagal theory: A biobehavioral journey to sociality. Comprehensive Psychoneuroendocrinology, 7, 100069. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpnec.2021.100069

Porges, S. W. (2023). The vagal paradox: A polyvagal solution. Comprehensive psychoneuroendocrinology, 16, 100200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpnec.2023.100200

Porges, S. W. (2025). Polyvagal Theory: Current Status, Clinical Applications, and Future Directions. Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 22(3), 169. https://doi.org/10.36131/cnfioritieditore20250301

Reid, T., Nielson, C., & Wormwood, J. B. (2025). Measuring Arousal: Promises and Pitfalls. Affective Science, 6(2), 369-379. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42761-024-00288-4

Roffey, M. (2025). The Polyvagal Theory–Fact or Fiction?.

Taylor, E. W., Wang, T., & Leite, C. A. (2022). An overview of the phylogeny of cardiorespiratory control in vertebrates with some reflections on the ‘Polyvagal Theory’. Biological psychology, 172, 108382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2022.108382

Waxenbaum, J. A., Reddy, V., & Varacallo, M. A. (2023). Anatomy, autonomic nervous system. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing.