Motivation and emotion/Book/2025/Pain avoidance motivation

How does avoidance of physical pain shape motivated action?

Overview

Scenario Emma, a 32-year-old office worker, developed acute lower back pain after lifting a heavy box while moving into her new home. The pain subsided after a few weeks, but during recovery, she noticed a sharp discomfort when bending or twisting. Fearing injuring herself again, Emma began avoiding the activities she once enjoyed, such as gardening and yoga. She even started taking the lift instead of stairs at work out of fear. In the beginning, her avoidance reduced her discomfort, but over time her muscles weakened and her pain sensitivity increased. When her physiotherapist suggested a gentle exercise program, Emma hesitated, remembering her initial injury and imagining it “snapping” her back again. As a result, she skipped most sessions, reinforcing her belief that physical activity would result in injury. This maintained a cycle of fear avoidance resulting in more pain. |

Pain is inherently aversive and serves as a powerful motivator. Like hunger, thirst, and other homeostatic drives, pain is a key tool for human survival (Navratilova & Porreca, 2014). When placed in an aversive state, we demand relief and are inherently motivated to leave this state of discomfort. As humans, we then learn to perform actions that prevent or terminate pain.

The biological processes influencing pain-avoidance motivation operate across several regions of the nervous system, often called the “pain matrix” (Yao et al., 2023). This matrix is split into two pathways. The lateral pathway encodes sensory information from noxious stimuli, like intensity and location, while the medial pathway governs the affective and motivational aspects of pain (Sewards & Sewards, 2002). Importantly, Pain relief is inherently rewarding, as it engages mesolimbic circuits such as the nucleus accumbens and ventral tegmental area (Porreca & Navratilova, 2017). These systems integrate dopamine release from pain relief and pain, shaping motivated action and reinforcing behaviours that protect against future harm.

From a psychological perspective, avoidance of pain can quickly turn maladaptive and become chronic. Chronic pain has been defined as pain that persists following an acute injury (Treede et al., 2015). This injury continues to cause pain beyond the natural healing process and no longer serves a protective role. Chronic pain patients have been found to display excessive avoidance of specific movements or activities, which is associated with worse outcomes (Vlaeyen & Linton, 2000). Several cognitive factors also influence an individual’s perception and susceptibility to pain, such as anticipation and personality (Ibrahim et al., 2020; Lu & Shih, 1997; Porro et al., 2002; Santos-Puerta & Peñacoba-Puente, 2022).

|

Focus questions

|

What is pain?

Pain is a subjective individual experience formed from sensory, affective and cognitive dimensions (Navratilova & Porreca, 2014). From an evolutionary perspective, pain is a call to action for an organism, just like hunger, thirst, or the desire to sleep. Like these needs, pain is also an aspect of the body's survival system which is responsible for protecting the organism (Denton et al., 2009). The unpleasant sensation of pain has evolved to create an aversive state that demands a behavioural change by motivating an organism to seek relief and to learn to predict and avoid dangerous situations in the future (Navratilova & Porreca, 2014). The characteristics of pain such as intensity, quality (e.g., burning, aching, prickling), and location are linked to the activation of nociceptors, a type of nerve cell that detects harmful stimuli and can initiate pain sensations (Gold & Gebhart, 2010).

Acute and chronic pain

Acute pain is defined as the physiological response to an adverse chemical, thermal, or mechanical stimulus (Carr & Goudas, 1999). In some individuals, pain that occurs following an acute injury continues to cause pain beyond the natural healing process and no longer serves a protective role. This is known as chronic pain. Chronic pain is used as an umbrella term referring to a wide range of conditions, defined as persistent pain lasting longer than three months (Treede et al., 2015). Unfortunately, research has been unsuccessful in determining what causes chronic pain (Crombez et al., 2012). Alongside the questions on the causes of chronic pain, Approaches to treatment often fail because they ignore the psychosocial factors and focus only on the presumed biomedical problems of the injury (Crombez et al., 2012).

Neuroscience of pain avoidance

Pain processing pathways

Pain is processed by a complex network of brain regions often referred to as the "pain matrix" (Yao et al., 2023). This network integrates sensory, emotional, and cognitive experiences. The brain regions responsible for processing pain has also been proposed to be functionally divided into two main ascending pathways (Sewards & Sewards, 2002a). The lateral pathway is primarily responsible for the sensory nature of pain processing, while the medial pathway focuses on the affective and motivational aspects

Lateral Ascending Pathway

The lateral sensory pathway is responsible for the sensory discriminative aspects of pain, such as intensity, location, and textual qualities (Yao et al., 2023). Although not directly tied to pain-avoidance and motivation, the lateral pathway is crucial for providing the sensory input necessary to identify a noxious stimulus.

Medial ascending pathway

_animation.gif)

The medial sensory pathway processes the affective and motivational dimensions of the experience of pain. These include the unpleasantness of pain and an individual’s drive to terminate or escape from pain (Sewards & Sewards, 2002b).The Anterior Cingulate Cortex (ACC) contributes by processing the emotional and affective components of pain. As well as this, the ACC represents the motivational aspect of pain processing, as it generates the motivation to terminate and escape from noxious stimuli (Fuchs et al., 2014). The prefrontal cortex (PFC) (See figure 2), specifically the medial prefrontal cortex, consolidates pain-related sensory characteristics, evaluates motivational factors, and computes motor circuits to relive or aggravate pain (Yao et al., 2023).

In the limbic system, The amygdala has been recognised as a unique site that influences pain modulation alongside its primary roles of processing of emotions and fear conditioning (Veinante et al., 2013). Dysfunction in the amygdala has been associated with increased risk of chronic pain development (Vachon-Presseau et al., 2016), as well as research finding that anxiety may partly result from problems with the amygdala regulating conditioned fear responses (Pare & Duvarci, 2012).

The relief of pain

The relief of pain is rewarding and can be motivating when an individual is in an aversive state (Porreca & Navratilova, 2017). Psychological research on pain relief has suggested that this satisfaction from leaving an aversive state could be one of the basic human emotions. Because the primordial emotions often signal that the individual is threatened, such as hunger or pain, they have been evolutionarily coded into circuits through different regions of the brain including the thalamus, insula and cingulate cortex. These areas of the brain have connections with the valuation/decision mesolimbic pathway. This circuit integrates and compares several competing emotional signals and chooses the action most beneficial for survival. The mesolimbic system can also help an organism learn what had caused the deviation and restoration of homeostasis, helping the organism avoid future painful situations (Porreca & Navratilova, 2017).

Reward-motivated circuits

Reward-motivated behaviour has previously been associated with dopamine neurotransmission in the region of the striatum called the nucleus acumbens (NAc), which receives dopamine signals from the ventral tegmental area of the brain (Porreca & Navratilova, 2017). Reward-related signals are also processed in frontal cortical regions such as the ACC (Narita et al., 2010), orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), and the PFC, which receive direct dopaminergic input and contribute to evaluating the value of actions and guiding future choices. In this context, the ACC is involved in learning from both rewarding and aversive outcomes, allowing the reward system to flexibly adjust behaviour based on previous experience. Pain and pain relief have been found to engage these same circuits (Wanigasekera et al., 2012). Studies using brain imaging have found acute painful stimuli activate reward-related regions including the OFC, and NAc. Pain has also been found to trigger dopamine release in the NAc.

The psychology of pain avoidance

Fear-avoidance model of pain

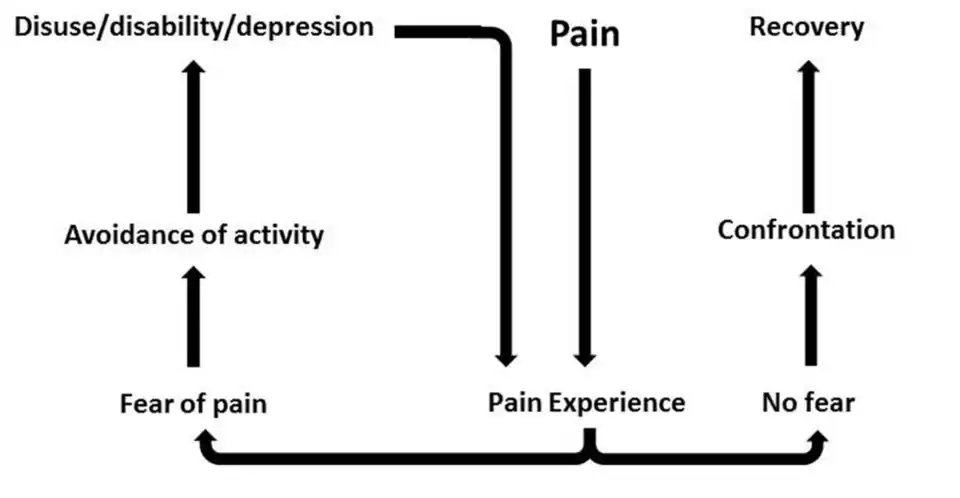

The Fear-Avoidance Model (see figure 3) suggests that when individuals find pain to be threatening or catastrophic, they develop pain-related fear (Lethem et al., 1983). These individuals develop an avoidance response which prevents the disconfirmation of fear and the maintenance of pain in the future. Vlaeyen and linton (2000) called this a "viscous cycle" of chronic pain. At the core of the model is the interpretation of pain. When pain is perceived as non-threatening, individuals are generally able to resume normal physical activity after a period of rest and avoidance. When the pain is catastrophised and misinterpreted as a sign of serious injury, it often leads to a heightened fear of pain. This fear can gradually extend to physical movements and result in the avoidance of activities believed to worsen the condition. Although avoidance behaviours serve a protective function when exposed to acute injury, excessive avoidance can limit the opportunities for an individual to correct their perception of the pain, leading to an overestimation of future pain and its consequences. Although avoidance make sense in the short-term after experiencing acute pain and is necessary to heal the body, persistence of these behaviours can become dysfunctional, leading to more pain and disability in the future (Vlaeyen & linton 2000).

The Fear-Avoidance Model explains pain avoidance as a fear-driven motivational system, where the desire to prevent pain overrides other goals. While this system can protect against injury in the short term, it also locks individuals into a cycle of avoidance that worsens long-term outcomes. Successful avoidance of feared movements is negatively reinforced because the feared outcome does not occur (Meulders, 2019). This mechanism causes the avoidance behaviour to become a stable response, persisting when the physical danger is no longer present.

Anticipation

The cognitive process of anticipation plays a significant role in modulating the perception of pain. Research has found that higher levels of pain anticipation is a significant predictor of increased perceived pain intensity (Santos-Puerta & Peñacoba-Puente, 2022). This expectation of pain also strongly predicts an individual’s drive to avoid the behaviour in the future, acting as a negative motivator. Research has highlighted that cortical nociceptive networks may directly be influenced by anticipation (Porro et al., 2002). The expectation of pain triggers top-down mechanisms that modulate these networks before the stimulus arrives, increasing activation in areas of the primary somatosensory cortex which are responsible for processing the initial sensory information of pain (Raju & Tadi, 2022). The ACC, insula, and medial prefrontal cortex are also activated, which are regions associated with the emotional and cognitive processing of pain (Porro et al., 2002).

Case study: Lasers!!!

Watson et al. (2009) investigated how placebo conditioning alters brain activity during both the anticipation and perception of pain. Eleven participants underwent fMRI scanning while receiving laser-induced pain on the forearm across a placebo and control session. In the placebo session, an inactive cream was applied and paired with reductions in stimulus intensity to create a placebo numbing effect, whereas in the control session participants were explicitly told the cream was inactive. Participants reported a significant pain reduction following conditioning, even when the painful stimulus was restored to its original intensity. The findings suggest that placebo effects are primarily mediated through modulation of anticipatory brain responses, which in turn sustain altered pain perception. The placebo analgesia worked largely because it reduced anticipation of pain. People expected less pain after the sham treatment, and this expectation altered their brain activity in ways that sustained lower pain ratings even when the painful stimulus was unchanged. This highlights the central role of expectation and learned association in shaping the experience of pain. |

Personality

Personality traits have been found to be significant determinants in the development and maintenance of chronic pain, primarily by moderating an individual’s motivation towards pain avoidance (Ibrahim et al., 2020; Martínez et al., 2011; Naylor et al., 2017). Using Cloninger’s Temperament and Character Inventory (Cloninger et al., 1993), research has suggested that there is a common personality profile across various chronic pain types (Naylor et al., 2017). In this review, a profile that included high scores of harm avoidance and lower self-directedness was identified. Individuals with high harm-avoidance are characterised by being worrying, fearful, and sensitive to criticism. Because of this, high harm-avoidance individuals are more predisposed to develop conditioned fear responses and specifically fear-avoidance responses. Low self-directedness individuals are often described as blaming, destructive, and lacking an internal locus of control. These traits prevent them from forming and achieving meaningful goals. This trait also worsens the viscous cycle of the fear-avoidance model, as the individual lacks the ability to develop adaptive coping strategies for overcoming pain avoidance.

The Big Five personality traits have also been found to be associated with pain avoidance, such as Neuroticism and Extraversion (Ibrahim et al., 2020). Neuroticism assesses an individual’s tendency to experience negative emotions and are more likely to find ordinary situations as highly threatening (Costa & McCrae, 1992). Neuroticism was associated with higher fear avoidance and catastrophic thinking in the context of chronic injury (Ibrahim et al., 2020). In contrast, Extraversion functioned as a protective factor and demonstrated a negative association with fear avoidance. The associated trait of positive emotionality found in Extraversion is connected to positive pain-related beliefs, and other traits like sociability and assertiveness are known to have a strong and direct effect on psychological well-being (Lu & Shih, 1997).

|

Test Time!

|

Applications and interventions

Rehabilitation

Understanding the motivation behind pain avoidance, which is rooted mainly in pain-related fear and catastrophic beliefs, can be used to inform specific interventions across many settings. The central mechanism of avoidance is the belief that pain signifies harm or injury (Crombez et al., 2012). As highlighted in the FA model, avoidance behaviour prevents corrective feedback and continues a viscous cycle of deconditioning and disability (Vlaeyen & Linton, 2000).

Interventions used to help overcome pain-avoidance and pain related fears generally fall under behavioural or cognitive approaches. These are designed to alter catastrophic interpretations and encourage engagement in feared activities (den Hollander et al., 2022; Zale & Ditre, 2015). Today, Fear-avoidance training (FAT) is common and is defined as an intervention that addresses fears and encourages normal activities and exercise (Zale & Ditre, 2015). Exposure-based therapies are often used in FAT and is seen as the gold standard when it comes to targeting avoidance behaviours driven by pain (den Hollander et al., 2022). Specifically, exposure in vivo involves developing an personal hierarchy of feared and avoided activities, followed by a graded confrontation of those activities (Zale & Ditre, 2015). The individual is encouraged to engage in a moderately feared activity until the disconfirmation of the maladaptive beliefs for the particular activity has happened. The individual would then proceed to the next item in the hierarchy of fearful situations until they are able to perform activities identified as most feared. Engaging in the feared activities associated with pain allows individuals to disconfirm their previous maladaptive beliefs (Zale & Ditre, 2015).

From the perspective of the FA model, a motivational and goal-oriented treatment style is commonly used. When the pain persists and several attempts to resolve the pain have failed, realistic rehabilitation may require an adjustment of unattainable goals (Van Damme et al., 2008). For individuals suffering from chronic pain, they may need to adjust their goals when they have become unrealistic as a result of pain. Patients might need to disengage from previously unsuccessful goal pursuits and reengage in other valuable goals that are less affected by pain. As well as this, the unsuccessful search for a solution to their pain problem can begin to chronically dominate life, often at the cost of other important goals. Because of this, individuals might need to give up the goal of complete pain relief and instead aim for a fulfilled life in the presence of pain (Eccleston & Crombez, 2007).

| Scenario: Goal Setting

Maria has fibromyalgia and experiences widespread pain. Traditional pain reduction strategies have failed. After seeing a therapist and working through how pain is stopping her from doing what she enjoys, she shifts her goals from eliminating pain to maintaining meaningful daily activities. Her motivation changes from avoidance to engagement in adaptive behaviours, improving quality of life and overall wellbeing. |

Conclusion

This chapter examines how the avoidance of physical pain can motivate human behaviour from neurobiological, psychological, and personality-based perspectives. As highlighted in this chapter, pain is not only a sensory experience but also consists of affective and cognitive dimensions that warn of harm and encourage people into protective behaviour (Navratilova & Porreca, 2014; Denton et al., 2009). From a psychological perspective, avoidance of pain can quickly turn maladaptive and become chronic. Chronic pain has been defined as pain that persists following an acute injury (Treede et al., 2015). This injury continues to cause pain beyond the natural healing process and no longer serves its protective role. Chronic patients have been found to display excessive avoidance of movements or activities, which is associated with worse outcomes (Vlaeyen & Linton, 2000). Although the avoidance of the behaviour that originally caused harm is protective for the acute injury, chronic fear avoidance can result in a cycle of more pain and disability.

From a neurobiological perspective, the processing of pain is completed a complex network of brain regions (Yao et al., 2023). Through the medial pathway, several brain regions input and modulate affective and motivational responses to guide actions aimed at avoiding pain or achieving relief (Sewards & Sewards, 2002b; Porreca & Navratilova, 2017).

Based on the research on pain avoidance motivation, the Fear-avoidance model provides a clear framework for understanding the motivational impact of pain. When individuals experience and interpret pain as catastrophic, they can develop a fear response that drives them to avoid certain behaviours (Vlaeyen & Linton, 2000). Anticipation of pain further amplifies avoidance by activating brain regions involved in sensory, emotional, and cognitive processing before movement occurs (Porro et al., 2002; Raju & Tadi, 2022). Personality and motivational drives also shape avoidance behaviours. Traits like high harm avoidance and neuroticism increase an individual’s sensitivity to threat and strengthen fear-driven avoidance (Naylor et al., 2017; Ibrahim et al., 2020). In contrast, Extraversion can promote resilience and positive beliefs about physical activity.

Understanding these mechanisms can inform interventions that aim to reshape motivated action. Behavioural and cognitive strategies like graded exposure and fear-avoidance training can target maladaptive beliefs and encourage participation in feared activities (Zale & Ditre, 2015; den Hollander et al., 2022). For some chronic pain patients, clinicians may want to step them away from previous unattainable goals of becoming pain free, and instead redirect motivation toward adaptive goals surrounding living a fulfilled life alongside pain (Eccleston & Crombez, 2007).

See also

- Motivation and emotion (Wikiversity) {{ic|Link to the most relevant book chapters)

- Chronic pain (Wikipedia)

- Motivation (Wikipedia)

References

Cloninger, C. R., Svrakic, D. M., & Przybeck, T. R. (1993). A psychobiological model of temperament and character. Archives of General Psychiatry, 50(12), 975–990. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820240059008

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Four ways five factors are basic. Personality and Individual Differences, 13(6), 653–665. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(92)90236-I

Crombez, G., Eccleston, C., Van Damme, S., Vlaeyen, J. W. S., & Karoly, P. (2012). Fear-avoidance model of chronic pain: The next generation. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 28(6), 475–483. https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0b013e3182385392

den Hollander, M., Smeets, R. J. E. M., van Meulenbroek, T., van Laake-Geelen, C. C. M., Baadjou, V. A., & Timmers, I. (2022). Exposure in Vivo as a Treatment Approach to Target Pain-Related Fear: Theory and New Insights From Research and Clinical Practice. Physical Therapy, 102(2), pzab270. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzab270

Denton, D. A., McKinley, M. J., Farrell, M., & Egan, G. F. (2009). The role of primordial emotions in the evolutionary origin of consciousness. Consciousness and Cognition, 18(2), 500–514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2008.06.009

Eccleston, C., & Crombez, G. (2007). Worry and chronic pain: A misdirected problem solving model. Pain, 132(3), 233–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2007.09.014

Fuchs, P. N., Peng, Y. B., Boyette-Davis, J. A., & Uhelski, M. L. (2014). The anterior cingulate cortex and pain processing. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience, 8, 35. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnint.2014.00035

Ibrahim, M. E., Weber, K., Courvoisier, D. S., & Genevay, S. (2020). Big Five Personality Traits and Disabling Chronic Low Back Pain: Association with Fear-Avoidance, Anxious and Depressive Moods. Journal of Pain Research, Volume 13, 745–754. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S237522

Lu, L., & Shih, J. B. (1997). Personality and happiness: Is mental health a mediator? Personality and Individual Differences, 22(2), 249–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(96)00187-0

Martínez, M. P., Sánchez, A. I., Miró, E., Medina, A., & Lami, M. J. (2011). The relationship between the fear-avoidance model of pain and personality traits in fibromyalgia patients. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 18(4), 380–391. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-011-9263-2

Meulders, A. (2019). From fear of movement-related pain and avoidance to chronic pain disability: A state-of-the-art review. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 26, 130–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2018.12.007

Narita, M., Matsushima, Y., Niikura, K., Narita, M., Takagi, S., Nakahara, K., Kurahashi, K., Abe, M., Saeki, M., Asato, M., Imai, S., Ikeda, K., Kuzumaki, N., & Suzuki, T. (2010). Implication of dopaminergic projection from the ventral tegmental area to the anterior cingulate cortex in μ-opioid-induced place preference. Addiction Biology, 15(4), 434–447. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1369-1600.2010.00249.x

Navratilova, E., & Porreca, F. (2014). Reward and motivation in pain and pain relief. Nature Neuroscience, 17(10), 1304–1312. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3811

Naylor, B., Boag, S., & Gustin, S. M. (2017). New evidence for a pain personality? A critical review of the last 120 years of pain and personality. Scandinavian Journal of Pain, 17(1), 58–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjpain.2017.07.011

Pare, D., & Duvarci, S. (2012). Amygdala microcircuits mediating fear expression and extinction. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 22(4), 717–723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2012.02.014

Porreca, F., & Navratilova, E. (2017). Reward, motivation and emotion of pain and its relief. Pain, 158(Suppl 1), S43–S49. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000798

Porro, C. A., Baraldi, P., Pagnoni, G., Serafini, M., Facchin, P., Maieron, M., & Nichelli, P. (2002). Does Anticipation of Pain Affect Cortical Nociceptive Systems? The Journal of Neuroscience, 22(8), 3206–3214. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-08-03206.2002

Raju, H., & Tadi, P. (2022). Neuroanatomy, Somatosensory Cortex. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK555915/

Santos-Puerta, N., & Peñacoba-Puente, C. (2022). Pain and Avoidance during and after Endodontic Therapy: The Role of Pain Anticipation and Self-Efficacy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1399. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031399

Sewards, T. V., & Sewards, M. (2002a). Separate, parallel sensory and hedonic pathways in the mammalian somatosensory system. Brain Research Bulletin, 58(3), 243–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0361-9230(02)00783-9

Sewards, T. V., & Sewards, M. A. (2002b). The medial pain system: Neural representations of the motivational aspect of pain. Brain Research Bulletin, 59(3), 163–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0361-9230(02)00864-X

Treede, R.-D., Rief, W., Barke, A., Aziz, Q., Bennett, M. I., Benoliel, R., Cohen, M., Evers, S., Finnerup, N. B., & First, M. B. (2015). A classification of chronic pain for ICD-11. Pain, 156(6), 1003-1007.

Vachon-Presseau, E., Centeno, M. V., Ren, W., Berger, S. E., Tétreault, P., Ghantous, M., Baria, A., Farmer, M., Baliki, M. N., Schnitzer, T. J., & Apkarian, A. V. (2016). The Emotional Brain as a Predictor and Amplifier of Chronic Pain. Journal of Dental Research, 95(6), 605–612. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034516638027

Van Damme, S., Crombez, G., & Eccleston, C. (2008). Coping with pain: A motivational perspective. Pain, 139(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2008.07.022

Veinante, P., Yalcin, I., & Barrot, M. (2013). The amygdala between sensation and affect: A role in pain. Journal of Molecular Psychiatry, 1(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/2049-9256-1-9

Vlaeyen, J. W. S., & Linton, S. J. (2000). Fear-avoidance and its consequences in chronic musculoskeletal pain: A state of the art. Pain, 85(3), 317–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00242-0

Wanigasekera, V., Lee, M. C., Rogers, R., Kong, Y., Leknes, S., Andersson, J., & Tracey, I. (2012). Baseline reward circuitry activity and trait reward responsiveness predict expression of opioid analgesia in healthy subjects. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109(43), 17705–17710. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1120201109

Yao, D., Chen, Y., & Chen, G. (2023). The role of pain modulation pathway and related brain regions in pain. Reviews in the Neurosciences, 34(8), 899–914. https://doi.org/10.1515/revneuro-2023-0037

Zale, E. L., & Ditre, J. W. (2015). Pain-related fear, disability, and the fear-avoidance model of chronic pain. Current Opinion in Psychology, 5, 24–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.03.014

External links

- Resources for individuals experiencing chronic pain (NSW Government)

- ACT Therapy techniques for chronic pain - (Integrative pain science institute)

- Six top tips for writing a great essay (University of Melbourne)

- The importance of structure (skillsyouneed.com)