Motivation and emotion/Book/2025/Neurodivergence and motivation

How do neurological variations influence motivation?

Overview

|

Scenario one Emily, a talented marketing specialist, is launching a new product. She struggles to concentrate during long meetings and finds routine tasks dull. Her impulsiveness and disorganisation often disrupt plans and cause missed deadlines. While creative work energises her, she tends to procrastinate on repetitive tasks. Her sensitivity to criticism and waning enthusiasm make it hard for her to stay motivated over time. |

Motivation is a key driving force behind our pursuit of goals and greatly influences our actions and decision-making. It arises from internal factors such as desires, values, beliefs, and emotions, as well as external influences like incentives, recognition, and support (Ryan & Deci, 2020). This chapter explores the complex relationship between neurological diversity—specifically attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and autism spectrum disorder (ASD)—and the subtle processes that motivate us to act, achieve, and connect with the world.

Individuals with ADHD and ASD often experience motivation differently compared to their neurotypical peers. We will explore the neurological foundations of these variations, including how differences in brain structure and function contribute to the distinct motivational profiles associated with these conditions. Our goal is to move beyond simple stereotypes and develop a deeper understanding of the challenges and strengths that neurodivergent individuals face as they pursue their goals.

By combining theoretical frameworks, such as self-determination theory (SDT), with insights from neuroscience, we aim to provide a comprehensive understanding of motivation in individuals with ADHD and ASD examining how impairments in executive functioning (EF), reward processing, sensory sensitivities, and emotional dysregulation (ED) impact motivation, while also highlighting opportunities such as hyperfocus, intense interests, and unique skills that can serve as powerful motivators.

Addressing these challenges requires robust support systems. Developing structured routines, maintaining clear communication, and employing effective coping strategies can help neurodivergent individuals manage their emotions and stress better. Recognising neurological diversity highlights the richness of human cognition (see Figure 1). By tailoring support to each individual, we can prevent overwhelm, minimise behavioural issues, and encourage resilience and motivation.

|

Focus questions

|

Understanding motivation: A theoretical framework

Motivation is the psychological process that initiates, guides, and maintains goal-oriented behaviours. It is broadly categorised based on the source of the driving force: intrinsic or extrinsic (Ryan & Deci, 2020; see Figure 2 and Table 1).

Intrinsic motivation

Arises from internal fulfilment and enjoyment. Individuals engage in activities for personal satisfaction rather than external rewards. When goals align with personal values and interests, it boosts commitment, well-being, creativity, and resilience.

Extrinsic motivation

Involves pursuing goals for external rewards, like money, grades, or recognition, rather than for personal enjoyment. This dependence on external validation influences goal-oriented behaviour.

| Intrinsic motivation | Extrinsic motivation |

|---|---|

| Focuses on internal rewards eg. enjoyment and pleasure | Focuses on external rewards eg. a reward or prize |

| Reading a book for enjoyment | Working a job to earn money |

| Playing sports for fun | Studying for a test to achieve a good grade |

| Volunteering to help others | Following the law to avoid fines |

| Engaging in hobbies, such as crafting | Entering a competition to win |

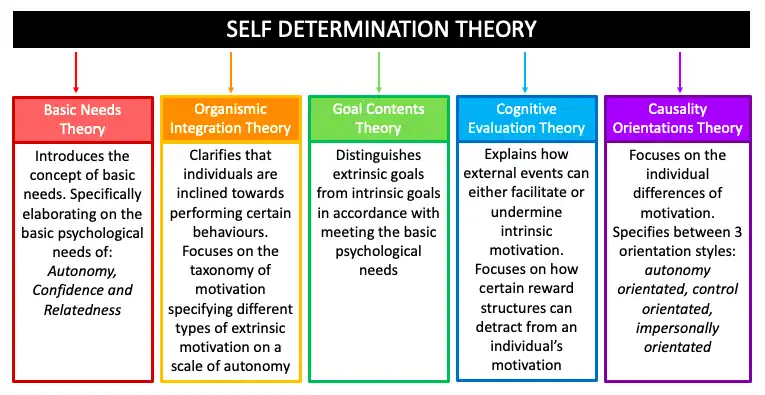

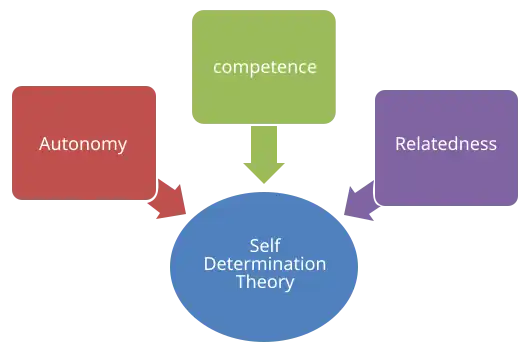

Self-determination theory

SDT is a comprehensive psychological framework that explores the complexities of human motivation and personality development. Developed by psychologists Edward L. Deci and Richard M. Ryan, this theory comprises five key sub-theories (see Figure 3).

Ryan and Deci (2020) expanded on their earlier work, emphasising the key differences between intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation. They state that people are most motivated when their needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness are fulfilled, as outlined in SDT.

Autonomy

The feeling of having control over one's actions. It encourages intrinsic motivation by fostering ownership and self-directed effort, leading to greater persistence through challenges when actions are self-chosen.

Competence

The desire to feel capable and successful. It motivates individuals to seek out and tackle challenges, develop skills, and grow. Confident individuals are more likely to choose tasks that promote personal development.

Relatedness

The innate longing to connect with others, influences motivation and behaviour by fostering a sense of belonging. This need drives people to pursue goals that align with both their own values and those of their social group.

SDT provides a deeper understanding of motivation by emphasising the importance of intrinsic factors, as well as the role that social and cultural contexts play in shaping our drive to learn, grow, and succeed.

The neuroscience of motivation

From a neurological perspective, motivation is a dynamic process involving multiple brain circuits that energise, direct, and sustain goal-oriented behaviour. These circuits evaluate the value of a reward, calculate the effort needed, and help maintain focus during execution. Motivation develops from basic drives to complex, purpose-driven actions, and can be divided into three main neurological stages: valence ("wanting"), arousal ("go"), and control ("how"). The interplay of specialised brain regions and neuromodulators shapes the strength, flexibility, and direction of motivated behaviour. Understanding this system is vital for recognising how neurodivergence impacts motivation and goal attainment (Salamone & Correa, 2024).

Key neurotransmitters in motivation

Motivation originates from a complex process involving a network of key neurotransmitters (see Table 2), each playing its own distinct role in shaping our behaviour and emotional well-being. Motivation is a dynamic process that involves the coordination of fast and slow signalling systems to determine incentive value, mobilise effort, assess risk, and focus on a goal.

| Neurotransmitter | Primary functional role | Key brain regions involved |

|---|---|---|

| Dopamine | Activation and effort calculation signal the salience and exertion associated with a reward, influencing both willingness to work and motor vigour (Salamone & Correa, 2024). | Ventral tegmental area (VTA) → nucleus accumbens (NAc) (reward system), prefrontal cortex (PFC), striatum. |

| Serotonin | Regulation and inhibition are essential for managing risk assessment and impulse control, and determining when to adjust or inhibit a current motivated behaviour. (Berger et al., 2009). | Raphe nuclei → PFC, limbic system, basal ganglia. |

| Norepinephrine | Arousal and vigour support the motivational state by boosting physiological arousal and alertness, thereby readying the body for the effortful execution of a chosen action (Slater et al., 2022). | Locus coeruleus (LC) (as a central nervous system modulator), adrenal medulla (as a hormone). |

| Acetylcholine | Focus and attention improve vigilance and stabilise memory formation by managing the signal-to-noise ratio of neuronal input during learning (Speranza et al., 2021). | The basal forebrain projects widely to the PFC and limbic system. |

| Glutamate | Encoding, learning, and stamina are influenced by the primary excitatory signal that encodes action-reward associations through synaptic plasticity. This signal is also linked to sustained performance capacity (Strasser et al., 2020). | PFC → striatum (basal ganglia), hippocampus (encoding context). |

| Neuromodulators, in a secondary yet essential role, regulate synaptic plasticity during learning (Palacios-Filardo & Mellor, 2019). | Hippocampus, PFC, striatum. |

Key brain regions involved in motivation

Neurotransmitter activity influences goal-directed behaviour through the coordinated functions of subcortical and cortical structures, known collectively as the motivational circuit (Rolls, 2025). This network assesses rewards and mobilises resources necessary to pursue them, integrating the key regions (see Table 3) to form the functional architecture that processes chemical signalling with EF to maintain effort towards long-term goals.

| Brain region/system | Role in motivation | Key neurotransmitter flow |

|---|---|---|

| Prefrontal cortex (PFC) | EF involves advanced planning, retaining information in working memory, and inhibiting unnecessary actions. It also influences long-term goals. (Ott & Nieder, 2019). | Heavy glutamatergic output drives action selection in the striatum, modulated by dopamine and acetylcholine. |

| Reward systems (VTA/NAc) | Valuation and activation involve assessing rewards and mobilising effort, both connected to 'wanting' (Berridge & Kringelbach, 2015). | Primary target for dopamine (VTA → NAc). Also receives critical glutamatergic input from the PFC and hippocampus. |

| Basal ganglia (striatum) | Action selection and execution involve converting motivational signals into motor commands through the Go/No-Go pathway (Speranza et al., 2021). | Fine-tuned by substantia nigra dopamine; receives substantial cortical glutamatergic input. |

| Limbic system (eg. hippocampus) | Contextual encoding transmits environmental and episodic memory, allowing the NAc to determine when and where to seek rewards (LeGates et al., 2018). | Primary site for glutamatergic long-term potentiation (encoding) and is heavily modulated by acetylcholine and serotonin. |

Neurological variations

| Scenario two

Liam, a detail-oriented data analyst skilled at identifying patterns, struggles with collaboration, brainstorming, and presentations. Open-plan offices and informal meetings overwhelm him, while vague instructions and shifting priorities cause anxiety and distraction. He finds small talk and networking draining, and as pressures mount, he skips meetings to focus on analysis, leading to disengagement and poorer performance. |

'Neurodivergence' is an umbrella term that refers to neurological variations that differ from what is considered typical (Kapp et al., 2013). This term includes conditions such as ASD, ADHD, dyslexia, dyspraxia, and Tourette's syndrome. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders fifth edition (DSM–5; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013), serves as the primary diagnostic tool for mental disorders. It outlines the criteria, symptoms, and diagnostic thresholds essential for ensuring consistency among healthcare professionals.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

ADHD is a neurodevelopmental disorder that begins in childhood and can persist into adulthood, characterised by inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity, which vary among individuals (Chaulagain et al., 2023). Impulsivity is characterised by making quick decisions without considering the consequences, such as interrupting, blurting out answers, or taking uncalculated risks.

These behaviours can disrupt focus, task completion, and responsibilities, often leading to lost concentration, disorganisation, procrastination, and missed deadlines (see Figure 4). Poor time management can hinder career progress, while impulsivity can cause misunderstandings or strained relationships (Faraone et al., 2024).

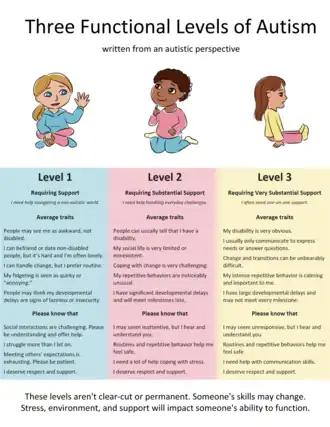

Autism spectrum disorder

ASD is a lifelong neurodevelopmental condition characterised by challenges in social communication and interpreting cues like facial expressions and tone of voice, which can lead to misunderstandings and social isolation. Individuals often have restricted interests and engage in repetitive behaviours—such as routines or stimming (e.g., hand-flapping, rocking)—to maintain stability or regulate sensory input (Hirota & King, 2023). ASD is classified into three support levels (see Figure 5), emphasising the importance of tailored supports, such as therapy, educational adjustments, and community resources, to assist individuals in managing daily life and reaching their full potential.

Co-occurring ADHD and ASD

ADHD frequently co-occurs with ASD, which makes distinguishing and accurately diagnosing both conditions more challenging. This overlap can increase the risk of other issues, such as anxiety and depression, further complicating daily life and functioning (Rong et al., 2021).

Neurological variations and motivation: ADHD and ASD

Motivational traits in neurodivergence reflect specific dysfunctions in key neural circuits responsible for setting goals, maintaining engagement, and directing attention. These conditions provide critical insights into how neuromodulatory variations directly influence motivation and effort.

Shared influences on motivation

Motivational traits in neurodivergent conditions such as ADHD and ASD provide vital insights into the neural processes that influence engagement, effort, and goal-oriented behaviours. These unique motivational characteristics stem from dysfunctions in key neural networks, particularly the PFC-striatum circuitry, which is essential for EF, planning, and reward processing.

Executive function deficits

Individuals with ASD and ADHD have notable EF deficits, particularly in inhibition and working memory, with comorbidity leading to even greater challenges (Ceruti et al., 2024). These problems directly reduce planning capacity and task initiation, making many activities feel overwhelming. This frequently results in avoidance and procrastination (Sadozai et al., 2024).

Attention regulation: hyperfocus

Many people with ADHD and ASD experience hyperfocus, a state of intense, sustained engagement in highly stimulating or intrinsically enjoyable activities. While this deep focus acts as a powerful motivator, enabling significant achievement in specific domains, it severely impairs attentional shifting when necessary. Research continues to explore the unique features of hyperfocus, often distinguishing it from similar deep engagement states, such as 'flow'. Despite its advantages as a motivator, hyperfocus can severely challenge task prioritisation and life balance (Ashinoff, 2021).

Atypical reward processing

Both conditions exhibit altered reward processing, often making typical social, delayed, or non-intrinsic rewards less effective motivators. This atypical response impacts participation in activities lacking immediate or personal relevance. Because ADHD co-occurs in approximately 38.5% of people with ASD (Rong et al., 2021), examining their shared and unique influences is crucial for understanding and supporting motivation in neurodivergent groups.

Condition-specific motivational profiles

ADHD

While ADHD is traditionally characterised by symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity, mounting research highlights that pervasive deficits in motivation are also a major, debilitating aspect of the condition. Importantly, these challenges are not due to laziness or lack of desire; instead, they arise from specific neurological differences in how the ADHD brain processes rewards, evaluates effort, and engages with long-term goals. Motivational traits in ADHD are closely linked to dysfunctions in catecholaminergic neurotransmitter systems, primarily involving dopamine and norepinephrine. These pathways originate in key brain regions, such as the VTA and the LC, and extend to the PFC and striatum (Faraone et al., 2024).

Dysregulation in these systems results in two primary issues:

Deficit in activation

Individuals with ADHD show altered dopamine pathways, which are crucial for reward and motivation, leading to reduced dopamine signalling (Wu et al., 2012). This means that activities motivating to neurotypical individuals may not have the same effect. They often struggle to initiate and sustain effort for tasks lacking immediate rewards—a deficit commonly referred to as a deficit in the activation component of motivation (Volkow et al., 2011).

Emotional dysregulation

This catecholamine imbalance manifests as ED, a significant and challenging feature of ADHD. Disrupted dopamine and norepinephrine signalling, particularly in adults, hampers the brain’s ability to regulate emotional intensity and employ executive strategies. Consequently, these dysfunctions lead to low frustration tolerance, emotional instability, and rapid mood swings—problems that significantly impact ongoing motivation and goal-directed behaviour (Soler-Gutiérrez et al., 2023).

ASD

Complex factors, including challenges with social cues, sensory processing, and distinctive EF profiles, influence motivation in individuals with ASD. These motivational differences vary considerably among people with ASD, emphasising the importance of recognising and supporting their diverse motivational drivers.

Reward processing and social impairments

Individuals with ASD process rewards differently, particularly in social contexts. Consequently, typical cues and incentives that encourage social involvement may be less effective. This can result in reduced motivation to participate in social activities that do not align with their interests, making it challenging to form meaningful social connections (Clements et al., 2018).

Sensory processing and self-regulation

Sensory processing differences significantly influence motivation in individuals with ASD, often manifesting as either heightened sensitivities or sensory seeking behaviours (Ben-Sasson et al., 2019).

Sensory sensitivity

Many people with ASD have strong reactions to sensory input, frequently leading them to avoid loud, bright, or crowded environments. This avoidance can lessen their willingness to participate and increase anxiety, restricting their involvement.

Sensory seeking

Conversely, some individuals are strongly driven by the need for specific sensory experiences. Actions such as fidgeting or self-stimulation (stimming) help regulate their arousal and achieve a desired alert or calming state, thereby supporting improved focus and engagement (see Figure 7).

Emotional dysregulation

ED significantly affects motivation in individuals with ASD. ED, characterised by difficulty managing the intensity and duration of emotional responses, is common within the autistic community (McDonald et al., 2024). This is closely linked to two main challenges: sensory overload and social impairments, where resulting strong negative emotions (distress, anxiety, frustration) lead to task avoidance or social withdrawal. Motivational behaviours, like stimming or engaging in restricted interests, may thus act as self-regulation strategies to achieve a more comfortable level of arousal and ease emotional discomfort.

Strategies to boost motivation in neurodivergent individuals

Understanding how neurological differences influence motivation is essential for supporting neurodivergent individuals. For those with ASD or ADHD, interventions based on SDT (which emphasise autonomy, competence, and relatedness—see Figure 8) are especially effective in enhancing intrinsic motivation (Di Domenico & Ryan, 2017). Taking a personalised and holistic approach helps identify challenges and leverage strengths, enabling neurodivergent individuals to reach their full potential.

Effective motivational strategies

Interventions (see Table 4) should be carefully designed to address deficits in EF and reward processing while creating an optimal environment (Sadozai et al., 2024).

| Strategy | Action | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Enhancing competence | Breaking tasks into smaller steps | Provides frequent, attainable rewards to reduce cognitive load and prevent task paralysis, maintaining high engagement. |

| Fostering autonomy | Integrating personal interests and strengths | Fosters enthusiasm and productivity through personal meaning, ownership, and self-motivation. |

| Providing structure | Setting clear and specific expectations | Establishes structure, reduces anxiety, and enhances focus by channelling energy. |

| Promoting relatedness | Cultivating supportive environments | Belonging and psychological safety reduce anxiety and enhance engagement. |

| Optimising engagement | Incorporating diverse learning modalities | Supports diverse attention and processing needs, enhancing engagement and accommodating sensory-seeking behaviours. |

Test your knowledge

Quiz

|

Conclusion

Understanding the connection between neurological differences and motivation is essential for building effective support systems for neurodivergent individuals, such as those with ASD, ADHD, and other cognitive variations. Each person’s unique neurological profile shapes motivation: some are driven by internal interests, while others are more influenced by external rewards or social recognition.

Neurological differences like ADHD and autism impact the brain’s reward and control systems, which in turn affect motivation. For example, ADHD involves catecholaminergic dysfunction (dopamine/norepinephrine), making delayed rewards less motivating and causing challenges with ED. This often hinders task persistence, particularly with activities lacking immediate gratification.

In ASD, motivation is often tied to sensory needs and focused interests, with conventional social rewards playing a relatively minor role. As a result, some individuals may withdraw socially or develop self-stimulatory behaviours ("stimming") to regulate themselves.

Both ADHD and ASD can involve executive function deficits that undermine planning and self-control, leading to avoidant behaviour. Interventions based on SDT, which emphasise autonomy, competence, and relatedness, are most effective in fostering motivation and overcoming these challenges.

By recognising these unique motivational pathways, we can design more inclusive, empowering environments that maximise potential and support lifelong growth and well-being for neurodivergent individuals.

See also

- ADHD and motivation (Book chapter, 2022)

- Autism and motivation (Book chapter, 2024)

- Motivational theories (Wikipedia)

References

Ashinoff, B. K., & Abu-Akel, A. (2021). Hyperfocus: The forgotten frontier of attention. Psychological Research, 85(1), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-019-01245-8

Ben-Sasson, A., Gal, E., Fluss, R., Katz-Zetler, N., & Cermak, S. A. (2019). Update of a meta-analysis of sensory symptoms in ASD: A new decade of research. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(12), 4974-4996. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04180-0

Berger, M., Gray, J. A., & Roth, B. L. (2009). The expanded biology of serotonin. Annual Review of Medicine, 60(Volume 60, 2009), 355-366. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.med.60.042307.110802

Berridge, K. C., & Kringelbach, M. L. (2015). Pleasure systems in the brain. Neuron, 86(3), 646-664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2015.02.018

Chaulagain, A., Lyhmann, I., Halmøy, A., Widding-Havneraas, T., Nyttingnes, O., Bjelland, I., & Mykletun, A. (2023). A systematic meta-review of systematic reviews on attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Eur Psychiatry, 66(1), e90. https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2023.2451

Clements, C. C., Zoltowski, A. R., Yankowitz, L. D., Yerys, B. E., Schultz, R. T., & Herrington, J. D. (2018). Evaluation of the social motivation hypothesis of autism: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(8), 797-808. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.1100

Ceruti, C., Mingozzi, A., Scionti, N., & Marzocchi, G. M. (2024). Comparing executive functions in children and adolescents with autism and ADHD—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Children, 11(4), 473. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11040473

Di Domenico, S. I., & Ryan, R. M. (2017). The emerging neuroscience of intrinsic motivation: A new frontier in self-determination research. Front Hum Neurosci, 11, 145. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2017.00145

Faraone, S. V., Bellgrove, M. A., Brikell, I., Cortese, S., Hartman, C. A., Hollis, C., Newcorn, J. H., Philipsen, A., Polanczyk, G. V., Rubia, K., Sibley, M. H., & Buitelaar, J. K. (2024). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (Primer). Nature Reviews. Disease Primers, 10(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-024-00495-0

Hirota, T., & King, B. H. (2023). Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Review. JAMA, 329(2), 157-168. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.23661

LeGates, T. A., Kvarta, M. D., Tooley, J. R., Francis, T. C., Lobo, M. K., Creed, M. C., & Thompson, S. M. (2018). Reward behaviour is regulated by the strength of hippocampus–nucleus accumbens synapses. Nature, 564(7735), 258-262. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0740-8

McDonald, R. G., Cargill, M. I., Khawar, S., & Kang, E. (2024). Emotion dysregulation in autism: A meta-analysis. Autism, 28(12), 2986-3001. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613241257605

Ott, T., & Nieder, A. (2019). Dopamine and cognitive control in prefrontal cortex. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 23(3), 213-234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2018.12.006

Palacios-Filardo, J., & Mellor, J. R. (2019). Neuromodulation of hippocampal long-term synaptic plasticity. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 54, 37-43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2018.08.009

Rong, Y., Yang, C.-J., Jin, Y., & Wang, Y. (2021). Prevalence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in individuals with autism spectrum disorder: A meta-analysis. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 83, 101759. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2021.101759

Rolls, E. T. (2023). Emotion, motivation, decision-making, the orbitofrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, and the amygdala. Brain Structure and Function, 228(5), 1201-1257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00429-023-02644-9

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101860

Sadozai, A. K., Sun, C., Demetriou, E. A., Lampit, A., Munro, M., Perry, N., Boulton, K. A., & Guastella, A. J. (2024). Executive function in children with neurodevelopmental conditions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nature Human Behaviour, 8(12), 2357-2366. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-024-02000-9

Salamone, J. D., & Correa, M. (2024). The neurobiology of activational aspects of motivation: Exertion of effort, effort-based decision making, and the role of dopamine. Annual Review of Psychology, 75(Volume 75, 2024), 1-32. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-020223-012208

Slater, C., Liu, Y., Weiss, E., Yu, K., & Wang, Q. (2022). The neuromodulatory role of the noradrenergic and cholinergic systems and their interplay in cognitive functions: A focused review. Brain Sciences, 12(7), 890. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12070890

Soler-Gutiérrez, A. M., Pérez-González, J. C., & Mayas, J. (2023). Evidence of emotion dysregulation as a core symptom of adult ADHD: A systematic review. PLoS One, 18(1), e0280131. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0280131

Speranza, L., di Porzio, U., Viggiano, D., de Donato, A., & Volpicelli, F. (2021). Dopamine: The neuromodulator of long-term synaptic plasticity, reward and movement control. Cells, 10(4), 735. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10040735

Strasser, A., Luksys, G., Xin, L., Pessiglione, M., Gruetter, R., & Sandi, C. (2020). Glutamine-to-glutamate ratio in the nucleus accumbens predicts effort-based motivated performance in humans. Neuropsychopharmacology, 45(12), 2048-2057. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-020-0760-6

Volkow, N. D., Wang, G. J., Newcorn, J. H., Kollins, S. H., Wigal, T. L., Telang, F., Fowler, J. S., Goldstein, R. Z., Klein, N., Logan, J., Wong, C., & Swanson, J. M. (2011). Motivation deficit in ADHD is associated with dysfunction of the dopamine reward pathway. Mol Psychiatry, 16(11), 1147-1154. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2010.97

Wu, J., Xiao, H., Sun, H., Zou, L., & Zhu, L.-Q. (2012). Role of dopamine receptors in ADHD: A systematic meta-analysis. Molecular Neurobiology, 45(3), 605-620. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-012-8278-5

External links

- ADHD Australia (

- Autism Awareness Australia (

- How Dopamine Affects Learning and Motivation in ADHD Brains (YouTube Video, How to ADHD, 2021)

- Neurodivergent Motivation: How to Overcome Task Paralysis & Boost Your Drive (Blue Sky Learning, 2024)

- Raising Children (Neurodiversity and neurodivergence: a guide for families, Raising Children)