Motivation and emotion/Book/2025/Lighting and mood

How does exposure to different lighting conditions affect mood?

Overview

Meet Sigurd, a resident of Tromsø, Norway, who experiences this polar night each year. As the daylight fades to almost nothing, Sigurd notices his energy draining, his mood sinking, and his nights stretching longer with restless sleep. He feels sluggish and disconnected, struggling to find motivation in daily tasks. Throughout this time, the lack of natural light disrupts his internal biological clock, making it difficult to maintain a regular sleep schedule and regulate his emotions. |

Light is a fundamental element of our environment, helping us to shape not only how we see the world, but also how we feel, think, and behave, both at conscious and unconscious levels. Beyond just enabling us to see, light can influence our biological processes, emotional regulation, and cognitive performance (Vandewalle et al., 2009; Wurtman, 1975).

Lighting conditions unsuited to their environment, whether in the home, workplace, school or in public spaces, can disrupt biological and psychological processes that drive mood regulation (Bedrosian & Nelson, 2017). For instance, research has demonstrated that insufficient daylight exposure can lead to depressive disorders, such as Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) (Partonen & Lönnqvist, 1998; Rosenthal, 1984), while excessive or poorly calibrated artificial lighting has been linked with heightened stress, reduced concentration, and visual discomfort (Begemann et al., 1997; Knez, 1995).

Given that many people living in industrialised societies spend the majority of their time indoors (Klepeis et al., 2001), the quality and characteristics of artificial lighting have become a determinant of psychological well-being and both long and short term mental health (Lunn et al., 2017). In this chapter, we will delve into the complex interplay of environmental, biological and psychological factors that underpin the relationship between mood and lighting.

|

Focus questions

|

What is mood?

Mood is a sustained, affective state that shapes an individual’s perception, cognition, and behaviour over extended periods of time (Clark et al., 2018; Sekhon & Gupta, 2023). Unlike brief and intense emotions, such as fear or joy, moods are enduring and are less directly tied to specific stimuli (Beedie et al., 2005). Moods can vary along a spectrum ranging from positive states, such as happiness and contentment, to more negative states such as sadness and irritability. Research demonstrates moods are the result of both internal biological fluctuations such as hormonal and neurotransmitter changes and external environmental influences (Rautio et al., 2017; Wirz-Justice, 2006).

Mood regulation is influenced by multiple neurotransmitters and hormones, such as serotonin, dopamine and norepinephrine (Jiang et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2018), and imbalances in these systems are often linked to depression and anxiety disorders. Along with these major neuromodulators, several key brain structures are implicated in the shaping of moods, namely the amygdala, prefrontal cortex (PFC) and thalamus. These all aid in the integration of sensory information relevant to a person's mental and emotional state (Drevets, 2006).

Light as biological mood regulator

Light plays an important role in regulating mood through its effects on both circadian rhythms and the body's hormonal systems. The body’s internal clock relies on external cues to align certain processes, including telling our body when to be alert.

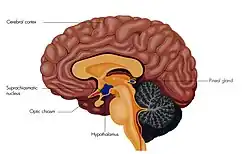

The suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) in the hypothalamus (see Figure 3), receives light information and coordinates timing signals to peripheral clocks throughout the body which tell the body when to be alert or when to be at rest (Weaver, 1998). This light information is detected by intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGCs), and are especially sensitive to blue light (Do & Yau, 2010). These cells send signals directly to the SCN through the retinohypothalamic tract, operating independently of vision and responding to overall brightness. After receiving this information, the SCN then controls the release or suppression of melatonin and cortisol, which modulates the body's sleep-wake cycle and alertness in accordance with the amount of available light (Castaño et al., 2019).

Natural light

The impact of light on circadian rhythms varies depending on its source, with natural and artificial light each affecting the body in different ways. Sunlight changes brightness throughout the day, helping to regulate and synchronise circadian rhythm by providing cues.

Circadian alignment

As light is the primary cue for synchronising circadian rhythms, regular exposure to daylight helps to stabilise the internal body clock, whereas irregular or poorly timed artificial lighting (such as the prolonged use of screens at night) suppresses melatonin and disrupts these circadian rhythms (Green et al., 2017, Tähkämö et al., 2018). Morning daylight exposure is linked to improved mood and more stable sleep-wake patterns, and has proved a key treatment component for seasonal disorders (Figueiro et al., 2017).

Unique qualities of natural light

Natural light has a broad spectral range, including ultraviolet radiation, and temporal variations, which can have biological effects not accounted for in current standards for artificial lights (Thorington, 1985). Higher illuminance levels are associated with improved alertness and cognitive performance. Exposure to bright light during the day can increase mood and reduce drowsiness. (Campbell & Dawson, 1990; Smolders et al., 2012).

Artificial light

Despite it being a school night, Sarah decides to finish the new season of the show she has been waiting for. After a disappointingly anti-climactic finale, she looks up to find the clock is reading well into the early hours of the morning. Resigned to her fate, she sets her alarm to go off in a few hours, and lays back down. Despite her obvious signs of fatigue, the short-wavelength blue light emitted from the screen has confused her brain, and she will still be awake and unable to sleep when the morning sun begins to glare through her bedroom curtains... |

Artificial lighting, such as that from screens/LEDS or fluorescents, halogens, neon lighting, HID lights) can either mimic these natural light patterns or disrupt them, which influence sleep quality and subsequently, mood (LeGates et al., 2014).

Wavelength variation

Differing wavelengths can influence hormone secretion/brain activity, with the short-wavelength blue light (470 nm) having been found to suppress melatonin secretion, and promote wakefulness and concentration (Chellappa et al., 2011). Long-wavelength red light (650 nm) has been evidenced to promote the release of melatonin (Milone et al., 2015), and can encourage relaxation and calmness (Chen et al., 2024; Ham et al., 2022).

Night exposure and irregular light environments

Light exposure at night, common in many environments such as offices or hospitals, is linked to disrupted circadian rhythm, impaired emotional regulation and heightened stress responses (Cajochen et al., 2011; Tähkämö et al., 2018).

Prolonged exposure to environments with irregular light has been linked to mood disorders and cognitive deficits (Bedrosian & Nelson, 2017; Bedrosian & Nelson, 2013).

Clinical and therapeutic applications of light

Controlled exposure to specific lighting conditions have been applied to improve both general wellbeing and in the treatment of specific mood and sleep disorders, applying the biological effects of light on circadian rhythms, hormone release and alertness.

Bright light therapy

One of the most established applications is bright light therapy, which involves daily exposure to intense artificial light (around 10,000 lux) for up to 20 to 30 minutes a day (Kogan & Guilford, 1998). Bright light therapy has been shown to be particularly effective in the treatment of Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD), where it helps decrease depressive symptoms brought on by the reduced daylight in winter months (Pail et al., 2011). Research also suggests it may have benefits outside the treatment of SAD, with several studies indicating improved sleep, energy and overall mood (Pail et al., 2011; Wirz-Justice, 2006).

Lighting in psychiatric and medical settings

The therapeutic potential of light-based treatments has also been investigated within the context of clinical environments. Optimised hospital lighting can reduce stress and support patient recovery (Dalke et al., 2006), and blue-enriched light can increase alertness in night-shift workers (Campbell & Dawson, 1990, Chellappa et al., 2011; Smolders et al., 2012). However, findings remain uncertain, with studies on dynamic lighting systems designed to mimic natural light patterns have shown results in increasing circadian health (Zhang et al., 2020), whilst other studies reported no significant effects on staff wellbeing (Simons et al., 2018).

Emerging applications of light

New research is currently exploring the potential benefits of personalised or adaptive light systems in workplaces and schools, which allow for adjustments in intensity and colour temperature in an effort to support alertness, focus and mood throughout the day (Barkmann et al., 2012). Light therapy has also shown promise in cognitive improvement for those with ADHD, and as a potential alternative to medication for antepartum depression (Terman, 2007).

Conclusion

Light is more than simply a means of vision, it is an important regulator of human biology, cognition, and emotion. Through its influence on circadian rhythms, hormonal systems and neural processes, lighting conditions help shape and contribute to the determination of mood, alertness and long-term mental health. Research demonstrates that whilst natural daylight supports healthy circadian rhythms and wellbeing, poorly timed or inappropriate artificial light can disrupt sleep and contribute to stress, cognitive impairment and mood disorders. Clinical applications, such as bright light therapy, help showcase the therapeutic potential of harnessing light exposure, and innovations into adaptive lighting suggest promising avenues for the enhancement of psychological health in everyday urban environments. Further research into the interaction between light and mood may help inform not only medical interventions, but the design of homes, workplaces, and public spaces that can better support societal wellbeing.

See also

- Circadian rhythm (Wikipedia)

- Lighting (Wikipedia)

- Melatonin and circadian motivation (Book chapter, 2025)

- Mood (Wikipedia)

- Omega-3 fatty acids and mood (Book chapter, 2020)

References

Bedrosian, T. A., & Nelson, R. J. (2013). Influence of the modern light environment on mood. Molecular Psychiatry, 18(7), 751–757. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2013.70

Bedrosian, T. A., & Nelson, R. J. (2017). Timing of light exposure affects mood and brain circuits. Translational Psychiatry, 7(1), e1017–e1017. https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2016.262

Beedie, C., Terry, P., & Lane, A. (2005). Distinctions between emotion and mood. Cognition & Emotion, 19(6), 847–878. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930541000057

Begemann, S., van den Beld, G., & Dolora Tenner, A. (1997). Daylight, artificial light and people in an office environment, overview of visual and biological responses. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, 20(3), 231–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-8141(96)00053-4

Blume, C., Garbazza, C., & Spitschan, M. (2019). Effects of light on human circadian rhythms, sleep and mood. Somnology : Sleep Research and Sleep Medicine, 23(3), 147–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11818-019-00215-x

Bundo, M., Preisig, M., Merikangas, K. R., Glaus, J., Julien Vaucher, Gérard Waeber, Marques-Vidal, P., Strippoli, M.-P. F., Müller, T., Franco, O. H., & Ana Maria Vicedo-Cabrera. (2023). How ambient temperature affects mood: an ecological momentary assessment study in Switzerland. Environmental Health, 22(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-023-01003-9

Cajochen, C., Frey, S., Anders, D., Späti, J., Bues, M., Pross, A., Mager, R., Wirz-Justice, A., & Stefani, O. (2011). Evening exposure to a light-emitting diodes (LED)-backlit computer screen affects circadian physiology and cognitive performance. Journal of Applied Physiology, 110(5), 1432–1438. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00165.2011

Campbell, S. S., & Dawson, D. (1990). Enhancement of nighttime alertness and performance with bright ambient light. Physiology & Behavior, 48(2), 317–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/0031-9384(90)90320-4

Castaño, M. Y., Garrido, M., Rodríguez, A. B., & Gómez, M. Á. (2019). Melatonin Improves Mood Status and Quality of Life and Decreases Cortisol Levels in Fibromyalgia. Biological Research for Nursing, 21(1), 22–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/1099800418811634

Chellappa, S. L., Steiner, R., Blattner, P., Oelhafen, P., Götz, T., & Cajochen, C. (2011). Non-Visual Effects of Light on Melatonin, Alertness and Cognitive Performance: Can Blue-Enriched Light Keep Us Alert? PLoS ONE, 6(1), e16429. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0016429

Chen, Y., Wu, Q., & Wang, S. (2024). Investigating the biomechanical impact of lighting placement on visual and physical comfort in living room interior design. Molecular & Cellular Biomechanics, 21(4), 698–698. https://doi.org/10.62617/mcb698

Clark, J. E., Watson, S., & Friston, K. J. (2018). What is mood? A computational perspective. Psychological Medicine, 48(14), 2277–2284. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291718000430

Dalke, H., Little, J., Niemann, E., Camgoz, N., Steadman, G., Hill, S., & Stott, L. (2006). Colour and lighting in hospital design. Optics & Laser Technology, 38(4-6), 343–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlastec.2005.06.040

Do, M. T. H., & Yau, K.-W. (2010). Intrinsically Photosensitive Retinal Ganglion Cells. Physiological Reviews, 90(4), 1547–1581. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00013.2010

Drevets, W. C. (2006). Neuroimaging Abnormalities in the Amygdala in Mood Disorders. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 985(1), 420–444. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07098.x

Figueiro, M. G., Steverson, B., Heerwagen, J., Kampschroer, K., Hunter, C. M., Gonzales, K., Plitnick, B., & Rea, M. S. (2017). The impact of daytime light exposures on sleep and mood in office workers. Sleep Health, 3(3), 204–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2017.03.005

Fisk, A. S., Tam, S. K. E., Brown, L. A., Vyazovskiy, V. V., Bannerman, D. M., & Peirson, S. N. (2018). Light and Cognition: Roles for Circadian Rhythms, Sleep, and Arousal. Frontiers in Neurology, 9(56). https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2018.00056

Green, A., Cohen-Zion, M., Haim, A., & Dagan, Y. (2017). Evening light exposure to computer screens disrupts human sleep, biological rhythms, and attention abilities. Chronobiology International, 34(7), 855–865. https://doi.org/10.1080/07420528.2017.1324878

Ham, J., Wan, S., D. Lakens, J. Weda, & Roel Cuppen. (2022). The influence of lighting color and dynamics on atmosphere perception and relaxation. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/The-influence-of-lighting-color-and-dynamics-on-and-Ham-Wan/95b0f99bf099157d03172d8ebb470ebc5046e0f2

Howarth, E., & Hoffman, M. S. (1984). A multidimensional approach to the relationship between mood and weather. British Journal of Psychology, 75(1), 15–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8295.1984.tb02785.x

Jiang, Y., Zou, D., Li, Y., Gu, S., Dong, J., Ma, X., Xu, S., Wang, F., & Huang, J. H. (2022). Monoamine Neurotransmitters Control Basic Emotions and Affect Major Depressive Disorders. Pharmaceuticals, 15(10), 1203. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph15101203

Klepeis, N. E., Nelson, W. C., Ott, W. R., Robinson, J. P., Tsang, A. M., Switzer, P., Behar, J. V., Hern, S. C., & Engelmann, W. H. (2001). The National Human Activity Pattern Survey (NHAPS): a resource for assessing exposure to environmental pollutants. Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology, 11(3), 231–252. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jea.7500165

Knez, I. (1995). Effects of indoor lighting on mood and cognition. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 15(1), 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-4944(95)90013-6

Kogan, A. O., & Guilford, P. M. (1998). Side Effects of Short-Term 10,000-Lux Light Therapy. American Journal of Psychiatry, 155(2), 293–294. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.155.2.293

Kuller, R., & Laike, T. (1998). The impact of flicker from fluorescent lighting on well-being, performance and physiological arousal. Ergonomics, 41(4), 433–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/001401398186928

LeGates, T. A., Fernandez, D. C., & Hattar, S. (2014). Light as a central modulator of circadian rhythms, sleep and affect. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 15(7), 443–454. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3743

Liu, Y., Zhao, J., & Guo, W. (2018). Emotional Roles of Mono-Aminergic Neurotransmitters in Major Depressive Disorder and Anxiety Disorders. Frontiers in Psychology, 9(2201). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02201

Lunn, R. M., Blask, D. E., Coogan, A. N., Figueiro, M. G., Gorman, M. R., Hall, J. E., Hansen, J., Nelson, R. J., Panda, S., Smolensky, M. H., Stevens, R. G., Turek, F. W., Vermeulen, R., Carreón, T., Caruso, C. C., Lawson, C. C., Thayer, K. A., Twery, M. J., Ewens, A. D., & Garner, S. C. (2017). Health consequences of electric lighting practices in the modern world: A report on the National Toxicology Program’s workshop on shift work at night, artificial light at night, and circadian disruption. Science of the Total Environment, 607–608, 1073–1084. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.07.056

Milone, F. F., Bolner, A., Nordera, G. P., & Scalinci, S. Z. (2015). Pulsed Led’s Light at 650 nm Promote and at 470 nm Suppress Melatonin’s Secretion. Neuroscience and Medicine, 06(01), 35–41. https://doi.org/10.4236/nm.2015.61006

Nisbet, E. K., Zelenski, J. M., & Grandpierre, Z. (2019). Mindfulness in Nature Enhances Connectedness and Mood. Ecopsychology, 11(2), 81–91. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2018.0061

Pail, G., Huf, W., Pjrek, E., Winkler, D., Willeit, M., Praschak-Rieder, N., & Kasper, S. (2011). Bright-Light Therapy in the Treatment of Mood Disorders. Neuropsychobiology, 64(3), 152–162. https://doi.org/10.1159/000328950

Partonen, T., & Lönnqvist, J. (1998). Seasonal affective disorder. The Lancet, 352(9137), 1369–1374. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(98)01015-0

Rautio, N., Filatova, S., Lehtiniemi, H., & Miettunen, J. (2017). Living environment and its relationship to depressive mood: A systematic review. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 64(1), 92–103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764017744582

Rosenthal, N. E. (1984). Seasonal Affective Disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 41(1), 72. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1984.01790120076010

Sekhon, S., & Gupta, V. (2023). Mood Disorder. PubMed; StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK558911/

Simons, K. S., Boeijen, E. R. K., Mertens, M. C., Rood, P., de Jager, C. P. C., & van den Boogaard, M. (2018). Effect of Dynamic Light Application on Cognitive Performance and Well-being of Intensive Care Nurses. American Journal of Critical Care, 27(3), 245–248. https://doi.org/10.4037/ajcc2018908

Smolders, K. C. H. J., de Kort, Y. A. W., & Cluitmans, P. J. M. (2012). A higher illuminance induces alertness even during office hours: Findings on subjective measures, task performance and heart rate measures. Physiology & Behavior, 107(1), 7–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2012.04.028

Stone, N. J. (1998). Windows and Environmental Cues on Performance and Mood. Environment and Behavior, 30(3), 306–321. https://doi.org/10.1177/001391659803000303

Tähkämö, L., Partonen, T., & Pesonen, A.-K. (2018). Systematic review of light exposure impact on human circadian rhythm. Chronobiology International, 36(2), 151–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/07420528.2018.1527773

Terman, M. (2007). Evolving applications of light therapy. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 11(6), 497–507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2007.06.003

Thorington, L. (1985). Spectral, Irradiance, and Temporal Aspects of Natural and Artificial Light. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 453(1), 28–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1985.tb11796.x

Vandewalle, G., Maquet, P., & Dijk, D.-J. (2009). Light as a modulator of cognitive brain function. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 13(10), 429–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2009.07.004

Weaver, D. R. (1998). The suprachiasmatic nucleus: a 25-year retrospective. Journal of Biological Rhythms, 13(2), 100–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/074873098128999952

Wirz-Justice, A. (2006). Biological rhythm disturbances in mood disorders. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 21(Supplement 1), S11–S15. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.yic.0000195660.37267.cf

Wurtman, R. J. (1975). The effects of light on the human body. Scientific American, 233(1), 69–77. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1145170/

Zhang, R., Campanella, C., Aristizabal, S., Jamrozik, A., Zhao, J., Porter, P., Ly, S., & Bauer, B. A. (2020). Impacts of Dynamic LED Lighting on the Well-Being and Experience of Office Occupants. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(19), 7217. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197217