Motivation and emotion/Book/2025/Exteroception and emotion

What is the relationship between exteroception and emotional experience?

Overview

Imagine a bustling cafe on a stormy evening. While patrons whisper to one another, the light clatter of cups and plates from outside blends harmoniously with the sounds of the rain. The warm smell of brewed coffee pairs perfectly with pastries wafting through the air. All the feeling you get from the given stimuli makes you feel the need to relax. Even without the brain commanding you, your shoulders feel light, you breathe steadily, and you remain cognisant of the gentle sounds and scents enveloping you. There is a calm but mindful beat to your heart. This involvement illustrates exteroception—how your brain forms tactile details from the environment and shapes your emotional reaction in real time Toussaint, Heinzle, & Stephan, (2024) . cafe epitomises an emotional adventure that encompasses and exceeds physical locations. It is an experience sculpted by a person's perception of the surrounding world. |

Exteroception provides connection between the outside world and emotions. Most people do not realise the extent to which perception of external stimuli affects their emotions and anxiety, health and overall well-being . The significance of exteroception is very informative in the case of developmental and clinical psychology, as well as self-emotion regulatory practices Gross, Sheppes, & Urry,(2011); Power & Dalgleish,(2008).

|

What is exteroception?

Extraterosensory processing of external stimuli, such as sight, sound (often referred to as vision), touch and smell. Interracial perception involves observing internal states, while extracerebral percept is concerned with viewing the world from outside. The process of survival, social interaction, and emotional experience is based on exteroception, not a passive process. It is feasible to steer clear of danger, find solace in risk management, and develop relationships with others. Why? Exteroceptive input and behaviour regulation are interdependent, requiring cognitive, affective, and cultural processing, leading to the production of both immediate physiological responses and long-term patterns of regulation, well-being, or clinical outcomes.

Definition and scope of exteroception.

Exteroception is the perception of the environment, and it is analysed via the five human senses, namely sight, hearing, touch, smell and taste. On the other hand, interception on the body's interior and exteroception centres on the world inside the human body Toussaint et al.,(2024); Hazelton et al., (2023).

Theoretical framing.

To situate that definition within broader psychological theory, four complementary frameworks are useful. First, classical physiological theories (e.g., James–Lange) emphasise how sensory-triggered bodily changes are interpreted as emotion. Second, appraisal models stress that sensory input becomes emotional only after cognitive evaluation of its personal meaning. In the constructivist sense, Barrett and his colleagues suggest that exteroceptive signals function by combining pre-existing concepts and interceptive patterns to form emotions. The frameworks are not contradictory, but rather, they expose distinct processing levels (physiological, cognitive, conceptual, and social) that impact emotion through exteroception.

Mechanisms and functions of external sensory processing.

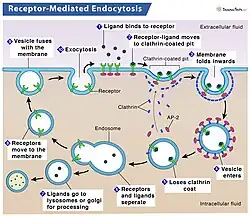

The external sense organs, together with the skin, have specialised receptors that transform external stimuli into electric signals, which are transmitted to the brain for further processing Toussaint, Heinzle, & Stephan, (2024). For instance, skin receptors that signal the presence of a hot object will activate a touch ''danger signal'' and lead to instant withdrawal. Hearing a loud sound is very attention-grabbing and could even activate basic defensive reflexes Vaaga & Westbrook, (2016). Freely and subconscious perceivable stimuli, such as a light breeze, faint smell of flowers, and many more, also aid active perception. Exteroception is also involved with proprioception (awareness of body position) and the vestibular system (balance and spatial orientation), which helps with physical coordination as well as stability Toussaint et al.,(2024).

Active sensing and attention.

Exteroception is not simply passive detection. The environment is sampled by the senses, which determine whether signals are sent to conscious awareness or stored in the background. Attention, expectation, and task demands are responsible for this. Practically, that means a faint aroma of coffee will likely remain background, but a sudden spill or shout will be up-weighted and may induce immediate physiological and affective responses.

The neural integration of exteroception and emotion

The human brain's fundamental function is to combine sensory information from the outside world with emotional states. The construction of emotional meaning is dependent on the ability to perceive environmental stimuli through a range of modalities such as vision, audition (exteroception), touch, taste, and smell. Sensory inputs are not isolated, but rather quickly analyzed for their affective value, which influences how people interpret threats, rewards, and social signals.The sensory cortex is connected to other neural circuits that are involved in emotion-related structures such as the amygdala, insula and prefrontal cortex, which can be amplified through immediate interpretation and regulation of affective responses. Sensory cues can trigger intense emotions and emotional states affect perception, as explained by the connections between these pathways. How does this work?

Neural pathways linking sensation and emotion.

The human being can blend exteroceptive sensory information with emotions as a result of several brain regions that facilitate the connection between emotions and sensory information. The initial stages of emotional processing Gross, Sheppes, & Urry, (2011); Power & Dalgleish, (2008). happen in a person's primary sensory cortices, each of which has its corresponding region, namely the visual cortex for sight, the auditory cortex for sound, the somatosensory cortex for touch, the olfactory and gustatory cortices for smell and taste, respectively. Toussaint et al., (2024).

Brain regions involved In emotional-sensory integration.

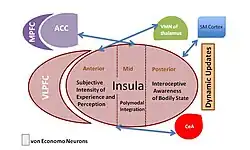

A sort of hub for the information with our internal sensations -- the region of it, called the Insula, influences physiological responses in the body. Adding to the affected part of emotion by influencing our subjective feelings. Toussaint et al., (2024). The Amygdala acts rapidly in assessing the emotional salience of any visual or auditory information to determine threats or rewards and will start immediate emotions such as fear or pleasure Hazelton et al., (2023). The prefrontal cortex modifies these responses by being situational and inhibiting impulses so that one behaves in a manner consistent with social norms. Toussaint et al., (2024). Crucially, states affect perception in a reciprocal sensory feedback. For instance, with anxiety, not only can there be an increased sensitivity to sensory stimuli, but also a general shift in the way that the sensory information is processed.

Emotional arousal activates the Autonomic nervous system and brings out changes in our bodies (e.g., increased heart rate and sweating) that can also serve to shape sensory experience.

Neuroscientific integration.

Contemporary imaging and lesion studies clarify these interactions. The amygdala and hippocampus receive fast, forward-feedforward signals from sensory cortices, while feedback from prefrontal and insular regions modifies perceptual gains and subjective experiences. The insula acts as a multimodal integrator, combining exteroceptive and interopceptual information to create 'how things feel' and provide embodied context for emotional interpretation of sensory events. This reciprocal circuitry explains how sensory events can produce immediate affect (fast, subcortical routes) and how context and regulation (slower, cortical routes) can reshape those responses.

Exteroceptive influences on emotional states

Emotions are not intrinsic, but they do arise and persist through sensory input from the environment. The brain is given signals about safety, threat and opportunity from external stimuli (light, sound, touch or smell or taste), which affects not only short-term emotional states but also longer-lasting mood states.The brain also receives these signals from different sources. These signals are referred to as exteroceptive signals. There are subtle yet powerful influences; for instance, blue and organized space brings calm, while clutter or darkness brings anxiety. Why? Similarly, soothing sounds like soothing music or birdsongs can serve as a distraction from noisy, chaotic sounds that provoke excitement and tension (Gross, Sheppey; Power & Dalgleish, 2008; Vaaga et al.).

Influence of sensory stimuli on emotional states.

The evidence indicates that external factors have a continuous impact on emotional states. People's spirits are lifted by affable and pleasant faces; dim lighting or disorderly conditions can make them feel uneasy Gross, Sheppes, & Urry, (2011); Power & Dalgleish, (2008).How does the use of tranquil music or birds differ from loud and erratic sounds in assisting with relaxation? Why? Vaaga & Westbrook, (2016); Toussaint et al., (2024).

Expanded examples and mechanisms.

Different sensory modalities influence emotion through partly distinct mechanisms. Visual cues (faces, posture, environmental affordances) provide rapid social and threat information; auditory cues (music, voices, sudden noises) shape temporal dynamics of arousal; touch conveys intimacy and safety through specialised C tactile afferents; olfactory signals link strongly to memory via the hippocampal and amygdala pathways; gustatory cues often have hedonic value linked to reward circuits. Spatial and temporal regularities in sensory input also shape predictability and safety: stable, predictable sensory input tends to lower vigilance and promote relaxation, whereas unpredictable input raises arousal and may prime fear responses.

Sensory experiences and their role in well-being.

Devoted emotions or repressed memories can be triggered by scents, with nostalgic and comforting notes being the most common, while unpleasant ones lead to sexual cravings Hazelton et al.,(2023).Touch is significant: touching something with suppleness helps to relax, but in distress when touched by something unpleasant or painful. Why? Toussaint et al., (2024).

The quality of well-being can be attributed to the sensory experience, with peaceful and harmonious sensory experiences being the basis for well-being, while noisy or chaotic environments can lead to stress and avoidance behaviours. American Psychological Association, n.d.; Gross et al., (2011).

Empirical nuance.

Longitudinal and intervention research suggest that modifications to sensory environments (such as exposure or relaxation to nature, soothing sounds, heightened lighting) significantly impact mood, cognition/stress levels. In healthcare and educational settings, evidence suggests that reduced noise, natural materials, and multisensory calm can reduce agitation and promote recovery, leading to more effective sensory design.

How do clinical and developmental factors factor into the study of emotion and emotions?

Understanding the study of emotion requires a thorough understanding of developmental and clinical aspects. In terms of development, the development of sensory experiences and early social interactions are key factors that influence emotions, attachments to and responses to environmental stimuli. What makes these processes adaptive? PTSD and mood disorders are among the psychological disorders that can be attributed to changes in sensory processing and atypical responses to environmental stimuli.

Sensory experiences in emotional and social development.

How does sensory experience contribute to the development of emotions? The development of emotional regulation, trust and connection is facilitated by touch Gross, Sheppeses, & Urry, (2011); Hazelton et al, (2023). As children age, their sensory processing skills improve and they acquire more complex social abilities, as well as the ability to recognise faces and voices through touch. Such processing can interfere with social functioning and emotional regulation, as noted by Baranek in (2002)and Tomchek and Koenig in (2016).

Developmental pathways.

Early caregiver-infant interactions foster dense multisensory learning environments that promote regulatory mechanisms. These environments include touch, voice, and visual attention. Recurrent safety signals, such as smooth motion and rhythmic sound, promote the development of secure attachment and parasympathetic regulation, leading to robust emotional responses that address later sensory impairments. Conversely, individuals may be exposed to sensory stimuli through early disorganised environments or neglect that result in dysregulated stress responses.

Impact of atypical sensory processing on mental Health.

An increased response to sensory stimuli is a common feature of PTSD and anxiety disorders, which are caused by environmental factors that intensify distress Van der Kolk, (2015); Rauch, Shin, & Phelps, (2006).Neglecting certain scents or sounds can lead to a change in the perception of depression and other mood disorders. Hazelton et al., (2023).

Clinical research emphasis.

Sensory hypersensitivity is a predictor of poorer outcomes across various anxiety and trauma disorders, as clinical studies indicate that individuals with strong sensory reactivity experience more avoidance, greater functional impairment, and increased physiological vigilance. Conversely, autonomic reactivity is reduced through the reduction of severity associated with graded exposure and interoceptive/exteroception-based (RE) grading while decreasing threat appraisal.

Somatic and sensory-based therapies

Therapeutic approaches that involve the body and sensory systems are now acknowledged as effective methods for regulating, recovering from trauma, and improving psychological well-being. Somatic and sensory-based therapies differ from talk therapies in that they prioritise the integration of physical sensations, sensory perception, and embodied awareness. This is more of a challenge to traditional talk therapy. These methods are based on the idea that emotional experiences are not limited to the mind but are fundamentally determined by bodily states and responses to environmental factors. Therapies that utilise sensory and bodily awareness can aid in building resilience, overcoming challenging emotions, while also improving self-management Porges, (2011).

Therapeutic approaches using sensory perception.

Therapies that involve sensory perception and body-based experiences aim to enhance emotional regulation by assisting individuals in the processing and tolerance of exteroceptive input Case-Smith & Arbesman, (2008).Mindfulness techniques improve sensory attention in the present moment, sensory integration therapies address sensory processing issues, and somatic experiences help to release stored bodily trauma. Kabat-Zinn, (2003); Porges, (2011). A more balanced and accepting relationship with sensory input is promoted by these modalities, which can help to diminish emotional reaction and promote overall health.

Practical examples and mechanisms.

- By observing sensory input without immediate appraisal, Mindfulness enhances attentional control and reduces reactive cycles.

- Techniques for establishing a foundation: employ uncomplicated, up-to-date exteroceptive anchors (such as 5 objects/signs) to prevent dissociation or panic.

- Music and art therapy utilise a systematic approach of auditory and visual exteroception to regulate mood and memory reconsolidation.

- Adaptive responses are enhanced and tolerance to sensory input is increased in patients who receive sensory integration therapy, particularly in paediatric settings.

Theoretical frameworks

- James–Lange theory of emotion The James–Lange account places exteroceptive-triggered bodily changes at the start of emotional experience: an external cue causes a bodily response, and the perception of that response is the emotion. This model highlights how exteroceptive input can act as a causal starting point for affect.

- Cannon–Bard theory Cannon and Bard proposed parallel processing: external stimuli evoke both physiological arousal and emotional feeling simultaneously, emphasising shared neural pathways for sensory processing and emotional response.

- Appraisal theory Appraisal perspectives specify that exteroceptive input becomes emotional only after evaluation for significance. Appraisal determines whether an event is judged as threat, opportunity, or irrelevant — thus shaping the quality and intensity of emotion.

- Constructivist/social frameworks Constructivist approaches (e.g., Barrett) emphasise that external signals are interpreted using conceptual knowledge and prior experience; social and cultural frameworks underline how community practices give sensory signals shared meaning.

Research findings

The study of exteroception has spread beyond the realms of science, spanning from neuroimaging to psychophysiology and from music to olfaction to cross-cultural research Hazelton et al., (2023); Toussaint, Heinzle, & Stephan, (2024); Power & Dalgleish, (2008); Vaaga & Westbrook, (2016); Robinson, Watkins, & Harmon-Jones, (2013); Cameron, (2001); Ballantyne, Fishman, & Rathmell, (2018); Gibbs, (2017). Every technique identifies different aspects of how external sensory cues can impact emotional encounters, influence control, and contribute to health or pathology. Researchers can investigate the neural and experiential connections between sensation and affect by examining evidence from all modalities Hazelton et al., (2023); Cameron, (2001); Robinson et al., (2013).

Neuroimaging evidence.

The rapid response of the amygdala to emotional sensory stimuli and the role of insula/prefrontal involvement in regulation of integration have been identified by functional neuroimaging. Hazelton et al., (2023); Toussaint, Heinzle, & Stephan, (2024).Multimodal imaging demonstrates how sensory cortices connect with limbic and regulatory networks, which supports the neural connection between exteroception and emotion.

Music and auditory research.

Music can be used for both spontaneous and therapeutic purposes, as it activates the reward, limbic, and motor circuits to alter mood and social connections. Power & Dalgleish, (2008); Vaaga & Westbrook, (2016).

Olfactory and gustatory research.

Odours are capable of granting access to limbic structures, and memories that trigger scents tend to be emotionally charged.The use of olfactory cues has been demonstrated in experimental and ecological studies to trigger vivid autobiographical memories and affective changes. Vaaga & Westbrook, (2016).

Cross-cultural and developmental research.

Emotional salience is influenced by cultural practices. Developmental input from early multisensory caregivers is predictive of later regulation capacity, and cultural contexts play a role in selecting sensory cues that convey comfort, danger or social belonging. American Psychological Association, n.d.; Robinson et al., (2013).

Clinical and psychophysiological work.

Psychophysiology uncovers extrateroceptive factors that impact defensive and autonomic responses, such as heart rate variability in the chest, skin conductance by the eyes, and startle.Although dysregulated sensory processing can lead to anxiety, PTSD, and other disorders, effective sensory interventions can alleviate symptoms.Clinical research has also shown this connection. Cameron, (2001); Ballantyne, Fishman, & Rathmell, (2018); Gibbs, (2017).

Bringing theory and research together

Sensory input from external sources is the main driver of emotional experience Toussaint, Heinzle, & Stephan, (2024). Rapid subcortical responses are linked to mood, social interpretations, cognitive appraisal, and clinical outcomes Cameron, (2001); Robinson, Watkins, Harmon-Jones et al, 2013; Gibbs: 2017; Ballantyne & Harmon–Junes 1997; Hazelton dr. (2023). Including these viewpoints allows for a multidimensional understanding of how external factors impact both positive and negative emotions. Physiological, social, cognitive, developmental, and clinical frameworks from classical to contemporary theories in psychology and neuroscience are utilized in this multilevel approach Toussaint et al., (2024); Cameron, (2001); Robinson et al., (2013); Gross et al., (2011); Gibbs, (2017).

At the fast subcortical level.

Exteroceptive cues at the fast subcortical level trigger immediate affective responses, which are based on Cannon-Bard and neurobiological models and involve amygdala and brain pathways. Toussaint et al., (2024); Hazelton et al., (2023)The swift pathways are designed for surviving: a sudden loud noise or shadow appearing above the ground initiates orienting, startling, or fight-or-flight reactions before conscious awareness. Higher-order emotional construction is based on research using subcortical circuits that prime the body to act within milliseconds, as demonstrated by studies of startle reflex modulation and fear-conditioning paradigms. Rapid responses can become maladaptive in contexts like PTSD, where even the most basic cues automatically trigger hyperarousal.

At the bodily level.

Sensory-triggered autonomic changes, such as heart rate, breathing, and galvanic skin response, are experienced at the bodily level, which contributes to emotional experience (as per James-Lange). Fear is not the sole cause of heart racing in a dark alley, but rather incorporated into the experience of experiencing it. Somatic markers theory goes beyond this by indicating that bodily states influence decision-making by diverging attention to specific outcomes. Through the manipulation of bodily signals, therapies like biofeedback or paced breathing can modify emotional states and promote a bidirectional exteroceptive-interopceptual loop. Cameron, (2001).

At the constructive and social level.

The social and constructive level of perceptions are determined by learned concepts and cultural meanings, which determine the labeling and social function of emotions resulting from sensory experiences. During festivals, loud collective singing may appear joyful and group-oriented in one culture while it can seem violent and intimidating in another. Social constructionist theories suggest that, according to social constructionists, emotions are not merely biological processes but also embedded in cultural script and practices. Robinson et al., (2013) According to cross-cultural psychology, culturally specific sensory and emotional mappings such as the use of ritual music and colour perception are influential in both multicultural therapy and mental health interventions.

At the cognitive level.

Goals, past experience, and context are the components of cognitive input appraisal processes. It also helps to decide whether a stimulus is menacing, not harmful or soothing. How do these processes work? A neutral face can be perceived as judgmental by an anxious person, while a positive stimulus can come across as friendly. Perception is filtered by appraisal through cognitive biases, such as attentional capture by threat or interpretive bias towards negativity. Evidence-based therapies are rooted in CBT, which involves cognitive reappraisal that alters the meaning of sensory cues while simultaneously changing emotional responses. Gross et al., (2011).

At the developmental level.

Sensory cues are connected to safety, regulation and trust in early caregiver-infant interactions at the developmental level. Safe attachment is promoted by regulating the infant's autonomic system through soothing touch, rhythmic rocking, and prosodic voice. Conversely, unbalanced or incongruous caregiving can cause children to react more quickly to warning signs of danger. This can hinder their ability to respond quickly. Early sensory-affective exchanges in adults have a significant impact on emotional regulation capacities, leading to changes in resilience, attachment patterns, and vulnerability to psychopathology, as per longitudinal studies. Gibbs, (2017).

At the clinical level.

The prevalence of anxiety, depression, trauma, and stress-related conditions is influenced by dysregulation in all these layers in clinical practice. Excessive subcortical reactivity causes hypervigilance, whereas blunted bodily awareness leads to emotional numbness. Negative biases are maintained by maladaptive cognitive appraisals, and the disruption of social-constructive processes impairs support and meaning-making. Interventions at various entry points can be utilized by clinicians through grounding techniques that target bodily cues, EMDR that uses sensory channels to consolidate traumatic memories, and cultural adaptations to therapy that ensure interventions are in line with clients' sensory-emotional frameworks. Ballantyne et al., (2018); Cameron,(2001); Gibbs, (2017). Efforts made to harness exteroceptive–emotional integration in clinical practice through emergent integrative approaches, such as somatic experiencing, rooms for sensory modulation, and trauma-informed design, have been shown to enhance regulation, healing, resilience, among others.

Conclusion

Exteroception is a process that takes the form of our brain and affects our experience or response to external stimuli. Instead of gathering inactive data, it interacts with our emotional responses Toussaint et al., (2024). Why? Objects, including sight, sound, scent and other stimuli, can impact mood, memory, and behaviour Vaaga & Westbrook, (2016).

Adaptive and meaningful responses to the world can be achieved through exteroceptive input and emotional processing. Why? The norm is for sensory and calm environments to offer protection/relief, but extreme or intense environments can cause stress (and anxiety). Why? What is the difference? Gross et al., (2011).Developing emotional memory through sensory and emotional experiences can lead to the formation of memories that will shape future experience. Hazelton et al., (2023).

These exteroceptive processing patterns or variations are connected to various mental illnesses, such as anxiety, PTSD, mood disorders, and autism spectrum disorder Van der Kolk, (2015); Baranek, (2002).The development of targeted therapies, such as sensory interventions and environmental changes, can be achieved through these connections to enhance emotional health and daily functioning. However, exterophobia , which is the study of how we interact with our emotional life internally, is not limited to mere perception. To succeed, one must have an understanding of what is outside the house. Toussaint et al., (2024).

The brain receives electrical signals from stimuli and processes them. Touching a hot beverage triggers skin receptor activity that signals danger, leading to swift withdrawal Vaaga & Westbrook, (2016). Those who are heard will react defensively by responding to the loud noise. The presence of delicate sensory signals, such as a fresh breeze or long-lasting floral scents, is essential to its survival. Maintaining physical coordination is also possible through the vestibular system and proprioception, which detect body position Toussaint et al., (2024).

See also

- Exteroception and emotion (Book chapter, 2024)

- wikipedia

- Wikiversity

- Wikiversity

References

Hazelton, J. L., Devenney, E., Ahmed, R. M., Burrell, J., Hwang, Y., Piguet, O., & Kumfor, F. (2023). Hemispheric contributions toward interoception and emotion recognition in left- vs right-semantic dementia. Neuropsychologia. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2023.108628

American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Emotion (Washington, D.C. : Online). https://library.canberra.edu.au/permalink/61ARL_CNB/esmov/alma991004667268103996

Power, M., & Dalgleish, T. (2008). What is emotion? Cognition and Emotion, 22(8), 1270–1300. DOI: 10.1016/S0376-6357(02)00078-5

Gross, J. J., Sheppes, G., & Urry, H. L. (2011). Cognition and Emotion Lecture at the 2010 SPSP Emotion Preconference: Emotion generation and emotion regulation: A distinction we should make (carefully). Cognition and Emotion, 25(5), 765–781. DOI: 10.1080/02699931.2011.555753

Vaaga, C. E., & Westbrook, G. L. (2016). Parallel processing of afferent olfactory sensory information. The Journal of Physiology, 594(22), 6715–6732. DOI: 10.1113/JP272755

Morrison, H., Salhab, J., Calvé-Genest, A., & Horava, T. (2015). Open Access Article Processing Charges: DOAJ Survey May 2014. Publications, 3(1), 1–16. DOI: 10.3389/fnins.2017.00411

Cameron, O. G. (2001). Visceral sensory neuroscience : Interoception. Oxford University Press, Incorporated.https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/canberra/detail.action?docID=430710.

Robinson, M. D., Watkins, E. R., & Harmon-Jones, E. (Eds.). (2013). Handbook of cognition and emotion. Guilford Publications. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/canberra/detail.action?docID=1186794

Ballantyne, J. C., Fishman, S. M., & Rathmell, J. P. (2018). Bonica's management of pain. Wolters Kluwer.ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/canberra/detail.action?docID=6023354

Gibbs, V. (2017). Self-regulation and mindfulness : Over 82 exercises and worksheets for sensory processing disorder, adhd, and autism spectrum disorder. PESI.https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/canberra/detail.action?docID=6260886

External links

Satpute AB, Kang J, Bickart KC, Yardley H, Wager TD, Barrett LF. Involvement of Sensory Regions in Affective Experience: A Meta-Analysis. Front Psychol. 2015 Dec 15;6:1860. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01860.

Kassab R, Alexandre F. Integration of exteroceptive and interoceptive information within the hippocampus: a computational study. Front Syst Neurosci. 2015 Jun 5;9:87. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2015.00087.

Chen WG, Schloesser D, Arensdorf AM, Simmons JM, Cui C, Valentino R, Gnadt JW, Nielsen L, Hillaire-Clarke CS, Spruance V, Horowitz TS, Vallejo YF, Langevin HM. The Emerging Science of Interoception: Sensing, Integrating, Interpreting, and Regulating Signals within the Self. Trends Neurosci. 2021 Jan;44(1):3-16. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2020.10.007.