Motivation and emotion/Book/2025/Cultivating awe

What practices or environments foster the experience of awe?

Overview - Aurora

|

Scenario: Sounds of the Aurora

Dr. Lamese and her colleagues stand on a frozen river underneath the dark winter sky in Finland, mesmerised by the rays of green and purple dancing above them. They've set up their equipment to be able to hear the movements of the northern lights and as Dr. Lamese heeds to the pops and crackles coming through her headphones, she is taken back by the vastness and enigmatism of our world. She's in a moment of awe that feels fleeting given the nature of this phenomena, yet in the same breathe time has stopped and all that exists is this luminous sky. |

The psychological concept of awe has historically been studied in relation to religion and philosophy to describe a state of transcendence and purposefulness to a greater being. It is explained in psychological terms as the cognitive perception of vastness, either physical i.e. outer space or conceptual i.e. destiny. A common identifier of awe is witnessing the presence of novelty or something 'bigger than oneself' where the 'small self' is elicited. Here, a cognitive process of accomodation is activated where the experience is integrated into an existing framework of knowledge (Schaffer et al., 2023).

Exposure to stimuli that are expansive, difficult for preexisting mental schemas, and connected to nature are necessary to cultivate awe.These elements frequently interact with contextual and cultural factors to determine whether awe is viewed as complex, positive, or negative. The breadth or significance needed to evoke this feeling is largely provided by the environment (Jiang et al., 2024).

Awe can change an individual's focus from their own needs to those of others, necessitating a new frame of reference as it allows people to envision themselves and their surroundings free of constraints from ego identification. As a result, awe is other-focused and organised by a desire to improve the well-being of others or by increasing the inclination of profound empathy and care (Luo et al., 2021).

Contrary to popular assumption, the experience of awe isn't a once-in-a-lifetime occurrence, observations of the everyday can demonstrate the frequency of this sensation. Awe has been seen to improve quality of life, causing people to wonder how one can uncover the awe formula and apply it in their daily lives.

Key Points:

- Background of awe studies are rooted in religion and philosophy

- Cognitive process to absorb new information at play (Schaffer et al., 2023)

- Awe drives individuals towards empathy and outward attention (Luo et al., 2021)

|

Focus questions

|

Mechanisms underlying awe

Awe is characterised as an experience due to the interplay of cognitive, neurological, and emotional processes whereby one experiences a connection to something larger than themselves while also subsequently feeling small in the larger picture (Chall et al., 2025).

Theories of awe

The first evolutionary theory of awe is presented by Keltner and Haidt (2003), who contend that the universal feeling of awe arises as a response to power. This is explained by the way in which a subordinate's response to social dominance strengthens social hierarchies and stabilises social groups. The emotion of awe becomes adaptive once there is a stable hierarchy because there are fewer power struggles or attempts to overthrow the group's leadership, and members have a better chance of surviving (Lucht & Van Schie, 2023).

Awe as an empirical experience

In order to consistently elicit awe in an experimental setting, Jiang et al. (2024) employed controlled laboratory stimuli like panoramic videos, captivating images, and personally relevant memories. Such stimuli improve the precision of experiments by enabling researchers to methodically extract reactions such as goosebumps or autonomic nervous system. These controlled stimuli are also beneficial because they isolate the particular effects of awe by reducing the impact of outside influences that are present in natural environments. However, the richness and depth of awe experiences found in natural settings cannot be entirely replicated by laboratory stimuli.

Researchers can quantify the intensity and occurrence of awe in a variety of settings by applying self-report and observational methods. Jiang et al. (2024) frequently used ecological momentary assessment methods such as experience sampling and daily diaries to measure the awe encountered in day-to-day living. Quantitative measures of awe at a macro level were obtained by analysing large-scale data sources, such as social media posts, for awe-related language and expressions (Jiang et al., 2024).

Psychological set up for awe

The psychological requisites for awe include openness to experience, concluded from Silvia et al. (2015) who compared the personality traits of openness to experience and extraversion as propensities for awe. They found that extraversion did not have a significant effect, whereas openness to experience was a strong predictor of awe. Models that define awe as a separate emotion from joy highlight its resemblance to other knowledge emotions such as interest, surprise, and confusion are supported by the distinction between extraversion and openness to experience (Silvia et al., 2015). The capacity of absorbtion is also seen as a personality trait, meaning the extent to which someone is able to immersed in the external world through sensory modalitiesa and attention to detail. This acts as a mediating factor as well as a predictor of frequancy of awe experiences (Tellegen & Atkinson, 1974; Van elk et al., 2016 as cited in Chen & Mongrain, 2021).

Compared to other aspects of personality, dispositional awe, the state in which people are awe-prone, is positively correlated with openness to experience. A lower desire for cognitive closure and a greater capacity for uncertainty have been linked to dispositional awe. Therefore, awe-prone people may naturally gravitate towards complex, uncertain, and information-rich scientific or aesthetic experiences as a result of this tolerance (Chen & Mongrain, 2021).

Cognitive components

The evolutionary explanation of awe and its mechanism is signified by Lucht and Van Schie's (2023) research describing that awe-evoking stimuli can cause the re-evaluation of pre-existing knowledge, and schemas being the appraisal accommodation for wonder and awe. In this context, reappraisal refers to the continuous assessment and reinterpretation of the awe experience, impacting other cognitive processes and emotional reactions. The success of this improves the comprehension and meaning-making, however, the failure of this may hold negative affect, which is explored further in this chapter (Lucht & Van Schie, 2023).

Neural Mechanisms

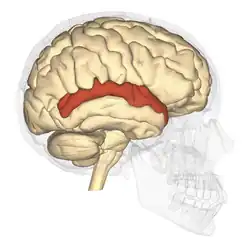

The brain activities that underline awe are diverse and involve a variety of networks, with the left middle temporal gyrus (MTG) serving as a key hub for schema processing - matching new stimuli with pre-existing schemas or knowledge structures. Its deactivation points to a process known as "schema liberation" in which experiencing awe entails momentarily letting go of preexisting mental models in order to make room for incomprehensible stimuli. The positive or threatening nature of the awe experience is correlated with increased connectivity with reward-related (cingulate cortex) or threat-related (amygdala) regions (Takano & Nomura, 2020) [provide further explanation for what these brain regions are and what there roles are specifically in relation to awe with an example]. Awe entails intricate neural circuitry that strikes a balance between emotional reactions, the need for schema revision, and the sense of vastness.

Key Points:

- Keltner and Hiedt, (2003) theory of awe centered around social cohesion and hierarchy and social stability.

- Researchers can precisely isolate and measure awe using lab-based stimuli, yet they are unable to capture the depth of natural awe experiences.

- Awe is strongly correlated with openness to experience, and those who are prone to awe exhibit a higher threshold for uncertainty (Chen & Mongrain, 2021).

- Awe entails reassessing preexisting knowledge and schemas, which, if successful, can improve meaning-making (Lucht & Van Schie, 2023)

- Deactivation of the left middle temporal gyrus (MTG) is the primary neural mechanism of awe (Takano & Nomura, 2020)

Factors and environments that cultivate awe

The predominant factors that commonly produce awe include the preception of vastness where one feels self transcendence and meaningful engagement with the natural world through creativity and human connection. There's no formula to this phenomena, nor is it a linear progression towards the goal of 'awe', but rather scale of moments that can be unlocked in the everyday.

The Small Self and Vastness

Awe-inducing experiences can boost self-transcendence, which enhances positive feelings. This suggests that the way awe affects emotional health may be mediated by self-transcendence (Chall et al., 2025). Specifically, when one experiences a redirection of their self-focus such like a diminished self concern or personal significance it can be considered as the state of 'the small self'. This feeling is categorised through the connection to something larger than oneself such as within nature, vast entities or big ideas (Piff et al., 2015). Examples of awe-eliciting stimuli have been seen to prompt the feeling of the small self in a positive framework, because they shift focus towards the outter world where recognition of power and meaning is enhanced. The small self is also related to increased prosocial behaviour such as generosity which not only directs energy outwards but also have positive well-being implications (Piff et al., 2015). This could be due to the recognition of ones place in a huge inetrlinked universe as the sense of vastness which is when stimuli is too much and overwhelming to comprehend, requiring a moment to process (Chen & Mongrain, 2020). Astronauts have described strong sensations of awe during their missions as the expanse of space inspires awe and fosters a sense of oneness with humanity (Yaden et al., 2016 as cited in Chen & Mongrain, 2020).

Nature, Creativity and Human connection

Self-referencial thought systems operate within the DMN which is essentially disengaged during awe because of the consistency of attention that is focused primarly outside (Chen & Mongrain, 2021), this includes areas like the angular gyrus, posterior cingulate cortex, and frontal pole. As the DMN is linked to rumination, daydreaming, and self-focused thought, its decreased activity indicates more present-moment engagement and less self-focused thinking (van Elk et al., 2019). Developing stratergies to strengthen this attention facillitate immersion, acting as a gateway to awe stimuli. An example of this is complete aborbption of sensory stimuli such as textures, colours and sounds (Ballew & Omoto, 2018 as cited in Chen & Mongrain, 2021).

To be in the presence of large mountains or rare natural phenomena can elicit the state of awe as it is a reflexive feeling. The root of the appraisal ultimately returns to how individuals perceive a diminished sense of self in relation to their broader surroundings. This allows people to move beyond the trusted enclosures of the normal, customary day-to-day reality of all existing things (Mateer, 2022)

Another element to this is meaning-making where inferences about the stimuli are made to facilitate the pathway to awe, Sawada et al., (2024) discovered in their mediation analyses that meaning-making through art boosted sentiments of being moved, as well as feelings of awe in the meaning inference condition (See figure 2). This is because it creates a sense of being moved and is highly specific to the individual and so it is important in inspiring people than simply appreciating beauty (Sawada et al., 2024)

Awe changes the perception of one-self into a modest form that allows for greater connection to higher values outside of the current state. It has seen to be linked to being sensitive towards others and having a stronger proclivity to care for others. It encourged individuals to form reciprocal connections of trust and aid, promoting a cohesive communal existence by reducing self-focus and shifting attention to others and one's social groupings. In doing so, it strengthens prosocial behaviour and collective participation through deep relationships with others and a feeling of shared identity and purpose (Piff et al., 2025)

Key Points:

- Self-transcendence as vital for experiencing awe and positive affect and has the potential to create prosocial responses (Chall et al., 2025; Piff et al., 2015).

- Nature, human connection, and creativity proven to elicit awe (Chen & Mongrain, 2021; Mateer, 2022; Sawada et al., 2024) because they are activities that drive focus outside of one's own self, involving a person's complete attention and submersion of senses.

- Meaning-making and ability for absorption influence the pathway to awe achievement (Chen & Mongrain, 2021; Sawada et al., 2024)

|

Quiz

|

Individual differences in awe

People perceive and absorb stimuli differently depending on numerous factors that increase or decrease their chances of awe, including demographics of age and cultures (Razavi et al., 2016; O'bi & Yang, 2024). It is important to note that the context in which awe is placed is crucial to determine its occurrence and frequency as people who consider themselves spiritually inclined have reported increased moments of awe (Bussing et al., 2021).

Demographic variances

Adults carry lived experience and knowledge to draw from when encountering new things whereas children have the opportunity to experience novelty towards ordinary life asspects, specifically awe-inspiring stimuli. Their interactions with these materials force them to further investigate and understand their environment and their relation to it, which holds the implication that their awe is an "epistemic emotion". This is because they have the ability to blur out the uncertainty that comes with awe and capture the motivational and cognitive advantages of wonder, especially due to their developing ability to intergrate complexities of the unfamiliar (O'bi & Yang, 2024).

While the notion of awe is accepted to be a universal concept the frequency and intensity with which people feel awe are impacted by cultural values, social structures and standard of daily experiences. Razavi et al., (2016) illustrates that people within cultures that value social heirarchy may feel awe more frquency if it is connected to social dominance or connection. In contrast the reduced frequency of awe could be attributed to cultural variations in daily emotional experiences rather than response bias (Razavi et al., 2016)

Awe can be expressed through religious contexts like prayer (see figure 3) which is an intentional attempt to strengthen self-trancendence, gratitutde and connection all of which are vital to awe. Bussing et al., (2021) suggest that religious individuals are more open to percieving awe due to these practices, such experiences are also available for secular people who cultivate readiness and opennes. This predesposition is also observed by Piff et al. (2024), explaining that individuals with religious backgrounds were more likely to experience awe after watching nature videos, reporting a higher sense of unity with others and the world around them in comparison to entertainment videos, therefore, spiritual methods can be seen and specific pathways to illicit awe (Bussing et al., 2021).

|

Case study - Awe in children

O'bi and Yang, (2024) investigated the perception of awe-related stimuli in children compared to adults in contrast with everyday scenarios. There were 97 adults and 199 children participants, a diverse sample of 58.33% White American and 11.17% Black American as well as other ethnicities. They were randomly allocated to watch breathtaking photographs from three categories; nature, disaster, slow motion and daily items. They were all individually evaluated by the researchers over Zoom sessions of about 10-15 minutes. They discovered substancial differences in children emotional response to the awe-related stimuli in comparison to the everyday items, amongst age-related variances. Children expressed a sentiments of amazement and anxiety, demonstrating a nuanced grasp of themselves and their relation to the novel material. |

Key points:

- Children are able to access awe through novelty experiences as well as learn and integrate new information within a positive frame (O'bi & Yang, 2024).

- Awe is a universal experience, yet its definition, frequency and intensity is influenced by the culture and context one resides in (Razavi et al., 2016).

- Specific pathways such as prayer can be an intentional incorporation of awe in the everyday (Bussing at al., 2021)

Positive and negative affect of awe

Awe is distinctive as it has versatile negative and a mainly positive connotation that is associated with wonder and amazement, often improving well being. However, cognitions of awe triggered by perceived threat may elicit adverse feelings such as anxiety when exposed to uncertainty or encountering an unexpected, possibly life-threatening incident (Schaffer et al., 2023). This has implications for future decision-making and cognitive frameworks for new stimuli (Guan et al., 2019; Ahmmad et al., 2022).

Wellbeing

When awe is percieved as a positive experience, it has the ability to increase the thought-action repertoiers and fosters the development of mental health resources like optimism which facilitate subjective well being. Zhang et al., (2024) implemented the "awe-walk" intervention, where older-adults were guided to excersions outdoors that were seen to increase their positive emotions and life satisfaction. This suggests that induced awe experiences can effectively improve well-being in vulnerable states, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic, where the higher frequency of awe experiences were linked to lower stress levels (Zhang et al., 2024).

Prosocial Behaviour

According to Inspiring-Helping Hypothesis, awe increases motivation to urge an individual to take actions that benifit others and other forms of alturism. Awe encourages the development of the quiet ego which, in turn, encourages prosocial behaviour and improves subjective wellbeing. Prosocial behaviour and awe have been observed to be possitivly correlated, since these behaviours like sharing and volunteering promote social connection and gratitidue, they in turn have a positive impact on ones mental and general well being.Therefore, by promoting actions that strengthen social bonds and cultivate positive emotional states, awe not only encourages prosocial behavior but also indirectly improves individual well-being (Zhang et al., 2024).

Negative awe

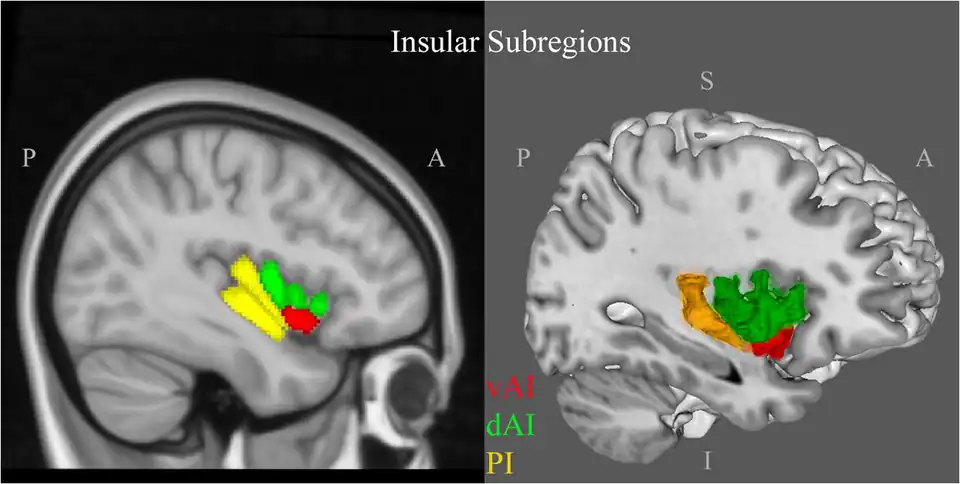

Negative awe is characterised by the feeling or uncertainty and helplessness in response to overwhelming stimuli where the assessment of risk and danger alerts stress and a loss of control, here the 'small self' has become a sense of danger. This sensation is observed in the insula and superior temporal gyrus (see figure 4) that are responsible for risk-assessment and body awareness, these assesments are mediated by the insula (see figure 5) which is involved in introspection (Guan et al., 2019). The ramifications of this experience are imposed on threat-processing and emotional control efficiency, where negative awe could cause survival-oriented reactions that hinder its positive effects. Understanding these underpinnings may guide treatments towards the mangagment of fear and the overwhelming unknown.

Ambiguity aversion

Threat-based awe can cause distortion to the decision-making process because of percieved vulnerability which creates a heavy reliance on familiarity as opposed to abiguity when analsying potential outcomes. This is a cognitive bias where individuls avoid options that have unknown features despite the chances of greater reward, which impairs decision making by reducing willingness and persuasion for new experiences, consequntly inhibiting creativity and growth (Ahmmad et al., 2022).

|

Case Study- Negative awe in the brain

Guan et al. (2019) saw that grey matter volume (rGMV) in brain regions like the insula and superior temporal gyrus are negatively correlated with people's experiences of negative awe, implying that people who have lower rGMV in these areas might be more likely to experience negative awe (see Figures 4 and 5). |

Key points:

- Not all experiences of awe have positive impacts (Shcaffer et al., 2023).

- Awe can reduce mind-wandering and self-referential thinking (van Elk et al., 2019).

- Positive awe is seen to encourage prosocial behaviour (Zhang et al., 2024).

- Negative awe can cause ambiguity aversion which can distort decision making (Ahmmad et al., 2022)

| Self-trancendence | reduction of self-focus and expansion of external perception | the 'small self' opens awe pathway |

|---|---|---|

| Vastness | a sense of larger than oneself in space, time and concept | the perception of scale such as a large mountain can illicit awe |

| Novelty | new and ambiguous stimuli force cognitive accomodation | novelty shifts the approach to stimulu making it more likely to provoke awe |

| Purposefulness | stimuli that requires intention and engagment of physical and cognitive senses | awe is magnified when one is able to create meaning from their experience |

| Nature | often embodes multiple awe-illiciting factors such as vastness and unpredictablility |

|---|---|

| Creativity | enganing with art requires meaning-making of stimuli |

| Human connection | interpersonal engagment can amplify awe because of shared meaning and depth |

Conclusion

Awe is a psychological phenomena that transforms self perception , inferences and social connection when large and unfamilar stimuli surpass established schemas, activating the accomodation process. Neural mechanisms like schema liberation as well as personality traits such as openness to experience can explain the reason for more or less frequency of awe experience. Awe is fostered in environments rich in vastness, novelty and purposeful actions because of their ability to evoke self-transcendence, meaning-making and prosocial behaviour. While awe experiences vary depending on culture and individual context like age, it is consistent that awe is recognised universally. Notably, awe is not always a positive experience, threat-based awe can cause confusion and ambiguity aversion which negate the positive impacts on well-being. The golden nugget is that awe can be activly cultivated with the approach of openness in seeking moments of beauty to expand ones knowledge and understanding of the world and their place in it, making awe a tool for growth.

See also

- Cherishing awe/An Awesome Big History of Religion (Wikiversity)

- Prosocial Behavior (Wikiversity)

- Overview Effect (Wikipedia)

References

Chall, A. M., & Kahn, J. H. (2025). Awe and Positive Affect: The Role of Self-Transcendence and Self-Focused Attention. Journalof Positive Psychology, 1–9. https://doi-org.ezproxy.canberra.edu.au/10.1080/17439760.2025.2499074

Chen, S. K., & Mongrain, M. (2021). Awe and the interconnected self. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 16(6), 770–778. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2020.1818808

Guan, F., Zhao, S., Chen, S., Lu, S., Chen, J., & Xiang, Y. (2019). The neural correlate difference between positive and negative awe. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2019.00206

Jiang, T., Hicks, J. A., Yuan, W., Yin, Y., Needy, L., & Vess, M. (2024). The unique nature and psychosocial implications of awe. Nature Reviews Psychology, 3(7), 475–488. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-024-00322-z

Keltner, D., & Haidt, J. (2003). Approaching awe, a moral, spiritual, and aesthetic emotion. Cognition & Emotion, 17(2), 297–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930302297

Lucht, A., & Van Schie, H. T. (2023). The Evolutionary Function of AWE: A review and Integrated model of seven theoretical perspectives. Emotion Review, 16(1), 46–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/17540739231197199

Luo, L., Mao, J., Chen, S., Gao, W., & Yuan, J. (2021). Psychological research of awe: Definition, functions, and application in psychotherapy. Stress and Brain, 1(1), 59–75. https://doi.org/10.26599/sab.2020.9060003

Mateer, T. J. (2022). Developing connectedness to nature in urban outdoor settings: a potential pathway through awe, solitude, and leisure. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.940939

Piff, P. K., Singhal, I., & Bai, Y. (2024). Bridging me to we: Awe is a conduit to cohesive collectives. Current Opinion in Psychology, 62, 101979. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2024.101979

Piff, P. K., Dietze, P., Feinberg, M., Stancato, D. M., & Keltner, D. (2015). Awe, the small self, and prosocial behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108(6), 883–899. https://doi-org.ezproxy.canberra.edu.au/10.1037/pspi0000018

Razavi, P., Zhang, J. W., Hekiert, D., Yoo, S. H., & Howell, R. T. (2016). Cross-cultural similarities and differences in the experience of awe. Emotion, 16(8), 1097–1101. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000225

Sawada, K., Koike, H., Murayama, A., Nishida, H., & Nomura, M. (2024). Appreciation processing evoking feelings of being moved and inspiration: Awe and meaning-making. Journal of Creativity, 34(1), 100076. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yjoc.2024.100076

Schaffer, V., Huckstepp, T., & Kannis-Dymand, L. (2023). Awe: A Systematic Review within a Cognitive Behavioural Framework and Proposed Cognitive Behavioural Model of Awe. International Journal of Applied Positive Psychology, 9(1), 101–136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-023-00116-3

Silvia, P. J., Fayn, K., Nusbaum, E. C., & Beaty, R. E. (2015b). Openness to experience and awe in response to nature and music: Personality and profound aesthetic experiences. Psychology of Aesthetics Creativity and the Arts, 9(4), 376–384. https://doi.org/10.1037/aca0000028 Takano, R., & Nomura, M. (2020). Neural representations of awe: Distinguishing common and distinct neural mechanisms. Emotion, 22(4), 669–677. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000771

Van Elk, M., Gomez, M. a. A., Van Der Zwaag, W., Van Schie, H. T., & Sauter, D. (2019). The neural correlates of the awe experience: Reduced default mode network activity during feelings of awe. Human Brain Mapping, 40(12), 3561–3574. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.24616

Zhang, J., Chang, B., & Fang, J. (2024). Awe influences prosocial behavior and subjective Well-Being through the quiet ego. Journal of Happiness Studies, 26(1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-024-00834-8

External links

- Awe in the Digital Age: The Role of Wonder and Terror in Our Relationship with Technology (Philosopheasy)

- Awe the Small Self and Prosocial Behavior (Journal of Personality and Social Psychology)

- How Scientist Measure Awe in the Wild (Youtube)

- Philosophy (Wikipedia)

- Piaget's Theory and Stages of Cognitive Development (SimplyPsychology)

- Religon(Wikipedia)* Strengthened social ties in disasters: Threat-awe encourages interdependent worldviews via powerlessness (Department of Social Psychology, The University of Tokyo)