Motivation and emotion/Book/2025/Aversion to happiness

What are the psychological mechanisms behind aversion to happiness?

Overview

|

Picture this ...

You just finished your last bit of university work for the week. You recall the all the late nights you had to endure, and the fear of missing several deadlines that kept you awake and working. You're incredibly exhausted and you want nothing more but to just eat dinner, kick your feet up, and watch your favourite show. However, once you sit down to relax, you can't help but feel like there's more to be done, that you just don't deserve to sit down and have time for yourself yet, otherwise something bad may happen. Suddenly, you're left with a plate of food you think you can eat only after you've done even more work ... |

Aversion to happiness (cherophobia) originates from the belief that experiencing situations that bring happiness may lead to negative consequences, such as causing moral decline, attracting misfortune, and inviting social envy. This concept developed as researchers examined personal, cultural, and cognitive factors that influence the willingness people have in experiencing and expressing joy. From a psychological standpoint, deeply held beliefs rooted in culture, such as the idea that happiness invites misfortune, enables individuals in their avoidance of pursuing happiness. Avoidant behaviour towards happiness becomes a concern when repeated suppression of experiencing positive emotions by an individual starts to be self-destructive, taking away life satisfaction, and harming interpersonal relationships.

This chapter raises awareness regarding the aversion to happiness, and highlight the psychological, theoretical, and social risks associated with this fixed mindset. Psychological mechanisms that discourage pursuing happiness will be discussed, as well as ways in which individuals express their aversion (see Figure 1) and how it affects them. The chapter examines relevant psychological theory that attempt to explain the motivation behind the aversion to happiness.

|

What is happiness?

Understanding the psychological definition of happiness is important in understanding why some individuals may avoid or fear this emotion. As an emotion, happiness is often studied by researchers under the umbrella of subjective wellbeing, compositing of life satisfaction, coping resources, and emotions, including positive affect (experiencing pleasant emotions), low negative affect (experiencing fewer unpleasant emotions), and a cognitive evaluation of one's life as both fulfilling and significant. (Cohn et al., 2009; Diener et al., 2018). While happiness is often regarded as a state of emotion desired by a majority of people, its meaning and value are defined by cultural, social, and individual factors specific to an individual (Behera et al., 2024). In many Western contexts, happiness is observed as an essential goal in life, tied to individualism and personal achievements (Zhang et al., 2024).

Because happiness may be defined and prioritised differently across contexts, it is crucial to understand that individuals will relate to happiness in different ways, which is a key point in exploring why some develop an aversion towards this emotion.

What is aversion to happiness?

Aversion to happiness (also referred to as cherophobia) is a fixed mindset characterised as a belief system in which individuals evade and repress their own pursuit of happiness. It is motivated by the conviction that experiencing or expressing happiness leads to detrimental outcomes such as bad luck, social backlash, and moral decline (Joshanloo, 2022; Joshanloo & Weijers, 2013).

Expressions of aversion to happiness include:

- Reluctance in expressing and acknowledging joy - avoiding intense displays of happiness due to concerns such as superstitions regarding bad luck, envy, and social judgement (Slemp et al., 2013).

- Emotional dampening - intentionally or subconsciously limiting the intensity of positive emotions to protect an individual's self from disappointment or vulnerability (Quiodbach et al., 2010).

- Discouragement of happiness seeking behaviours - the avoidance of activities that could generate joy, such as celebrations or rewarding experiences due to fear of triggering misfortune or appearing boastful (Joshanloo, 2013).

These attitudes function as psychological defence mechanisms, whereby an individual may keep expectations low in order to avoid future disappointment and perceived backlash toward experiencing happiness. It is also important to know that the aversion to happiness is not the same as depression, as it is an active avoidance of positive emotional states impacted by cultural and personal beliefs. For additional information, see book chapter on being too happy.

Psychological mechanisms behind the aversion to happiness

Aversion to happiness is often shaped by the fear of vulnerability, moral teachings, and cognitive biases. Outlining and understanding these factors is key to comprehending important differences in how individuals steer away from experiencing happiness.

Cognitive biases

Certain cognitive biases help explain some of the perspectives individuals may have when developing an aversion to happiness.

Negativity bias

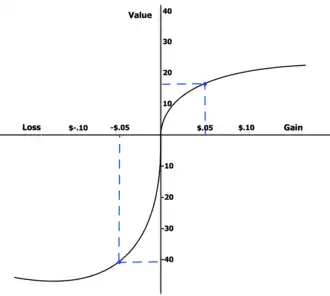

The negativity bias is a useful cognitive framework for understanding why some individuals are hesitant to express and experience happiness (see Figure 2). While this cognitive bias has served an adaptive purpose in the past by emphasising awareness towards dangerous situations, it may also distort an individual's emotional processing into perceiving happiness as unsafe. Individuals with a heightened negativity bias believe that positive experiences can be easily overshadowed by thoughts of potential disappointment, loss, or punishment (Vaish et al., 2008). This feeling of hopelessness may lead to the belief that happiness is a precursor to suffering, rather than basic adaptive emotion. As such, believing in this idea causes individuals to avoid experiencing and expressing happiness due to their anticipation of negative events. This anticipation of negativity encourages maladaptive avoidance and emotional dampening as expressing happiness is not seen as a desirable act, but as an act of risky exposure that will be followed by negative consequences.

Loss aversion

The loss aversion bias (see Figure 3) also proves as another key cognitive bias explaining why some individuals are averse to happiness. This bias explains that the tendency for potential losses to have greater psychological weight than potential gains (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979). In the context of emotion, happiness is often seen as a state in which the anticipated pain of its loss is understood to evoke more intense feelings rather than experiencing it. This imbalance encourages emotionally defensive strategies such as emotional dampening or suppression, where individuals will avoid experiencing joy in the fear of the experiencing the intense negative emotions that come with its potential loss. A recent study conducted by Koan et al. (2021) finds that individuals with lower levels of positive psychological well-being are more prone to loss-aversion in the context of decision making, suggesting that individuals unable to sustain positive states of emotion may actively avoid happiness to protect themselves from the emotional weight of potential loss.

Fear of vulnerability

A psychological mechanism underpinning aversion to happiness is the feeling of vulnerability that comes from emotional expression. Experiencing and expressing happiness require a certain level of openness and authenticity which leave some individuals feeling exposed to judgement and disappointment. A study conducted by Wood et al. (2003) regarding emotional regulation finds that individuals who view expressing happiness (positive affect) as socially risky may choose to suppress this emotion as a defensive strategy against feelings of vulnerability. The tendency to utilise this defensive strategy is prevalent in collectivist groups, where an overt display of happiness from an individual can be perceived as boastful and disruptive in group settings. As a result, individuals relate happiness with social threat, turning a basic emotional state into one that requires careful consideration or avoidance.

An aversion to happiness also functions as an anticipatory defence mechanism, which prompt individuals to restrict positive emotion to avoid the disappointment associated with possible negative events which could impact an individual after being in a state of vulnerability due to expressing happiness. Pre-emptive defensive behaviour such as this offers a sense of control, however, it restrains emotional expression and devalues one's well-being (Hofman & Hay, 2018). In a clinical context, this behaviour often leads to maladaptive coping styles and complex anxiety disorders where vulnerability is framed as a dangerous state of emotion instead of a necessary condition for healthy self-expression (Vassilopoulous, 2008).

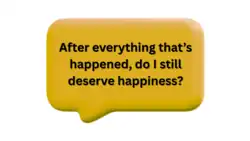

Self-esteem

Individuals who possess low self-esteem are more likely to hold negative self-schemas that lead them to believe they are undeserving of positive experiences, turning happiness into a less desirable state of emotion. In such cases, individuals believe that happiness is an emotional state that is "too good" for them, which may trigger feelings of shame, guilt, and anticipatory anxiety. Research regarding the fear of happiness indicates that individuals with low-self esteem have a higher tendency in engaging toward emotional dampening strategies, wherein one tends to downplay and suppress their own emotions in order to align with their own negative self-beliefs (Li et al., 2023). Recent studies reinforce the link of self-esteem with the aversion to happiness, finding that the latter mediates the relationship between self-esteem and psychological distress, suggesting that individuals with lower levels of self-esteem may perceive experiencing happiness as uncharacteristic of themselves (Joshanloo & Yildirim, 2024). These findings reflect the feeling on how some individuals may avoid happiness, if they feel like it is undeserved.

Low self-esteem is also linked with higher vulnerability to disappointment, and anticipated loss, which further shapes happiness as an emotion associated with risk. Additional cognitive theories regarding self-protection of one's emotions suggest that people with low self-worth will continue to avoid positive emotional states to shield themselves from potential loss (Baumeister et al., 2003). Further empirical findings align with this, as a study by Li et al. (2023) found that expressive suppression of emotions mediates the effects of having low self-esteem on depressive symptoms. Overall, these findings prove that low self-esteem not only facilitates a sense of undeserving positive emotions, but also impacts the ability of being emotionally vulnerable, reinforcing avoidant behaviour.

Adherence to culture and norms

Across many cultures, proverbs such as "crying comes after laughing" or "pride comes before the fall" are reflective of a belief that experiencing happiness attracts misfortune, such as how in Iran, a widespread superstition states that feeling or expressing joy may tempt fate to bring about negative events (Joshanloo, 2013). This belief may lead individuals to restraining their emotions expressing happiness as a method to prevent this from happening. Superstitious beliefs are a common pattern in East Asian societies, where displaying strong positive emotions are often avoided to prevent upsetting balance or drawing unwanted attention (Uchida et al., 2004).

There exist specific religious and philosophical traditions that describe overt displays of happiness as egoistic, hedonistic, or not applicable to humility. In some interpretations of Buddhism, attachment to pleasurable experiences is seen as a cause of suffering, which encourage individuals who practice Buddhism to maintain simple lives, rather than indulge in happiness (Joshanloo & Weijers, 2014). Certain strands of Christianity and Islam value modesty and restrain as well, understanding that excessive celebration is a distraction from one's religious duties (Abou El Fadl, 2014). While these teachings may promote balance and spiritual awareness, it is possible that they contribute to a reluctance in expressing happiness if taken to a certain extent (Miyamoto & Ma, 2011).

|

Paying attention?

|

Psychological theories behind aversion to happiness

Aversion to happiness can be further understood through different psychological theories and perspectives, such as the cognitive-behavioural perspective, attachment theory, self-discrepancy theory, and survivor's guilt. Each of these psychological concepts explain how personal experiences, interpersonal attachment styles, and incongruent views of one's self drive individuals away from experiencing happiness.

Cognitive-behavioural perspective

From a cognitive-behavioural perspective, aversion to happiness is reflective of maladaptive core beliefs, where the self is deemed unworthy of positive experiences. These beliefs are acquired from repeated life events where happiness was followed by negative outcomes, creating a form of associative learning and conditioning towards behaviour that expresses happiness (Beck, 1976). As result, individuals may adopt behavioural strategies such as emotional dampening, to proactively reduce vulnerability, suppressing the expression and experience of happiness (Quiodbach et al., 2010). Over time, the association between positive emotional states and perceived emotional threats can become deeply ingrained, which could cause further harm toward and individual's perspective on happiness. Further cognitive-behavioural interventions attempt to target these maladaptive behaviours through cognitive restructuring and controlled exposure to positive experiences, which enable individuals to re-evaluate their beliefs regarding happiness.

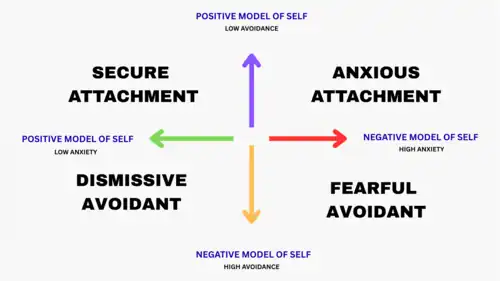

Attachment theory

The attachment theory suggests that early caregiving form expectations about safety, trust, and emotional expression (see Figure 4). In an emotional context, individuals with insecure or disorganised attachment histories whom are exposed to inconsistent and neglectful caregiving, may have learned that displays of happiness are unsafe, in which expressions of such are ignored, invalidated, or punished (Bowlby, 1969). As such, these issues may progress into adulthood where expressing happiness may trigger anxiety rather than comfort, specifically in interpersonal contexts and relationships. Research indicates that avoidant and disorganised attachment styles are the most strongly associated with the suppression of positive emotions and difficulty of maintaining states of of positive emotions, making individuals with these attachment styles more susceptible to avoiding happiness (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007). In a therapeutic context, exploring these attachment styles can lead to uncovering the reason behind why some individuals are averse to happiness, and can help individuals understand that experiencing happiness is safe and socially acceptable.

Self-discrepancy theory

The self-discrepancy theory suggests that an individual's actual self is incongruent with their ideal self, with positive experiences triggering guilt and shame in these specific cases. This means that happiness itself becomes a psychological issue, as experiencing joy highlights the individual's perceived understanding of who they are, versus who they should be (Higgins, 1989). In the context of aversion to happiness, experiences where in one expresses joy may highlight the discrepancy between an individual's ideal and real self, triggering anxiety, shame, or guilt, as experiencing happiness heightens their perspectives on their own inadequacies. As an example, individuals who focus on perfectionism may feel that experiencing happiness conflicts with their obligation to fixate on their highly demanding personal duties. This internal conflict facilitates the avoidance of positive emotions, which turns happiness into a perceived emotion that threatens their own personal obligations. Consequently, in order to maintain a sense of self-consistency between one's ideal self and real self, individuals may end up limiting their positive emotions and avoid expressing their happiness altogether.

Survivor's guilt

Survivor's guilt occurs when individuals who have endured trauma feel emotionally responsible for having escaped harm while others have suffered. In certain situations, experiencing happiness after a traumatic event may lead to individuals undergoing heavy guilt and shame responses to joy, as some may feel emotionally responsible for escaping their trauma. In some cases, happiness may feel like a betrayal toward those who have suffered similarly to those individuals, which leads to avoiding expressing and feeling happiness as a response (Lee et al., 2001). This sense of emotional responsibility turns happiness into a source of guilt and moral conflict, with positive emotions becoming associated with further shame and anxiety, on top of the initial guilt one may already feel from undergoing a traumatic experience. This avoidance of happiness can become habitual, making it even more difficult for survivors to experience or express joy in socially safe and positive contexts, reinforcing how traumatic events may end up weaponizing one's sense of moral obligations (Murray et al., 2021).

|

Case study: Jack

Jack has gone through a recent traumatic event in his life that has left him as his parents' only child. After the incident, he recalls times where he "catches" himself enjoying his time with his friends and family completely forgetting about the fact that he no longer has a sibiling. Sometimes, Jack restrains himself from feeling positive states of emotion, as he believes that he simply does not deserve to feel happy after experiencing a tragic loss. |

Table 1

Psychological theories and their association with aversion to happiness

| Theory | Effects |

|---|---|

| Cognitive behavioural perspective | Developed negative schemas regarding positive affect result in inability to experience and express happiness. |

| Attachment theory | Insecure and disorganised attachment styles lead to a fear of experiencing happiness due to unsafe early childhood environments. |

| Self-discrepancy theory | Incongruency with ideal self and real self result in an aversion of happiness due to shame and guilt towards discrepancies. |

| Survivor's guilt | Surviving a traumatic event results in dampened ability to experience and express happiness due to shame and guilt resulting from an incident. |

These psychological perspectives have the ability to make the suppression of expressing happiness an subconscious and protective response to learned behaviours, as its effectiveness builds up over time. While these behaviours are initially meant as adaptive responses in unstable social environments, continued and prolonged avoidance of positive emotions such as happiness can disrupt emotional resilience and significantly reduce life satisfaction (Werner-Seidler et al., 2013).

"Deserving" happiness

Overcoming the aversion to happiness begins with re-configuring beliefs about an individual's capacity to deserve happiness in the first place. Psychological research shows that self-compassion as a reflection based on an individual's strengths can help oneself internalise the idea that happiness and the experience of joy is not meant to be a reward for good behaviour. Experiencing happiness is not based on "deservingness", but is instead a natural part of one's life experiences (Callan et al., 2014).

Interventions and self-affirming exercises may help in reducing the difficulty in accepting happiness, and understanding the experience as an essential aspect of a healthy life, rather than an indulgence.

Cognitive behavioural therapy

Cognitive behavioural therapy plays a key role aiding individuals in identifying maladaptive thoughts such as "I don't deserve to be happy" or "Something unfortunate will happen if I express my joy". Cognitive restructuring and guided exposure as the core principles of cognitive behavioural therapy could result in replacing these negative and unhelpful thoughts with healthier and grounded perspectives regarding happiness. Over time, this allows the guilt and fear associated happiness to lessen, which would allow for people to fully appreciate positive emotions (Beck, 1979). Additionally, cognitive behavioural therapy encourages individuals to be practical and test their beliefs in real-life situations, helping them realise expressing happiness is safe and appropriate. Repeated practice of these cognitive and behavioural techniques helps strengthen an individual's resilience, allowing them to approach happiness proactively, rather than defensively.

Mindfulness and emotional awareness

Practicing mindfulness cultivates awareness of positive emotions that can complement cognitive approaches such as cognitive behavioural therapy. By being grounded and intentionally observing present experiences without judging how oneself feels, an individual may reduce the likelihood of suppressing their expressions of happiness, and increase positive emotional regulation (Keng et al., 2011). Mindfulness techniques including gratitude journaling, mindfulness meditation, and savoring exercises push individuals toward noticing and fully engaging with moments of happiness, which strengthen their capacity to express and experience happiness naturally. Habitual practice of these techniques will enable individuals express happiness without fear or guilt, and eventually enable them to seek out positive affects on their own. Through this, the factor of "deserving happiness" will be deemed as significantly less important than an how an individual originally believed it was.

|

Case study: James

Across the next few months, James starts to feel control over his emotions again. Through cognitive restructuring techniques, guided exposure, mindfulness exercises, and healthy challenges toward his previous beliefs on "deserving" happiness, he finally feels like he can breathe again. James starts to feel like he can smile when he wants to, without having to think about if he deserves to anymore. James has successfully restructured the way he thinks about being happy. |

Conclusion

Aversion to happiness is a complex psychological condition that is impacted by personal beliefs, and past experiences. Prolonged experiences of this condition may lead to chronic emotional suppression, which can negatively impact well-being and increase one's vulnerability toward more detrimental and destructive mental health issues. Psychological perspectives such as the attachment theory, self-discrepancy theory, cognitive-behavioural perspective, and survivor's guilt assist in understanding the causes and complexities individuals may also experience in their aversion to happiness. In terms of deserving happiness and possible cognitive treatments, cognitive behavioural therapy and mindfulness exercises may help reconstruct an individual's negative beliefs on experiencing and expressing happiness. Overall, multiple studies link the aversion to happiness condition to an individual's self-worth, proposing that if unhealthy personal beliefs are challenged in an appropriate and effective manner, perspectives on "deserving" happiness will change and individuals will be able to experience and express happiness without negative emotions.

See also

- Being too happy (Book chapter, 2019)

- Culture and positive psychology (Wikipedia)

- Experiential avoidance (Book chapter, 2013)

- Cognitive behavioural therapy (Wikipedia)

- Positive affectivity (Wikipedia)

References

Baumeister, R. F., Campbell, J. D., Krueger, J. I., & Vohs, K. D. (2003). Does High Self-Esteem Cause Better Performance, Interpersonal Success, Happiness, or Healthier Lifestyles?. Psychological science in the public interest : a journal of the American Psychological Society, 4(1), 1–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/1529-1006.01431

Beck, A. T. (1979). Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. Penguin.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Attachment. Basic Books.

Behera, D. K., Rahut, D. B., Padmaja, M., & Dash, A. K. (2024). Socioeconomic determinants of happiness: Empirical evidence from developed and developing countries. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 109, 102187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2024.102187

Callan, M. J., Kay, A. C., & Dawtry, R. J. (2014). Making sense of misfortune: Deservingness, self-esteem, and patterns of self-defeat. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 107(1), 142-162. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036640

Cohn, M. A., Fredrickson, B. L., Brown, S. L., Mikels, J. A., & Conway, A. M. (2009). Happiness unpacked: Positive emotions increase life satisfaction by building resilience. Emotion, 9(3), 361-368. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015952

Diener, E., Oishi, S. & Tay, L. (2018). Advances in subjective well-being research. Nat Hum Behav 2, 253–260. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0307-6

Higgins, E. T. (1989). Self-discrepancy theory: What patterns of self-beliefs cause people to suffer? Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 93-136. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0065-2601(08)60306-8

Hofmann, S. G., & Hay, A. C. (2018). Rethinking avoidance: Toward a balanced approach to avoidance in treating anxiety disorders. Journal of anxiety disorders, 55, 14–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.03.004

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1977). Prospect theory. An analysis of decision making under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263-292. https://doi.org/10.21236/ada045771

Keng, S., Smoski, M. J., & Robins, C. J. (2011). Effects of mindfulness on psychological health: A review of empirical studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(6), 1041-1056. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.04.006

Joshanloo, M. (2013). The influence of fear of happiness beliefs on responses to the satisfaction with life scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 54(5), 647-651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.11.011

Joshanloo, M. (2022). Predictors of aversion to happiness: New insights from a multi-national study. Motivation and Emotion, 47(3), 423-430. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-022-09954-1

Joshanloo, M., & Weijers, D. (2013). Aversion to happiness across cultures: A review of where and why people are averse to happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(3), 717-735. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9489-9

Joshanloo, M., & Yıldırım, M. (2024). Aversion to happiness mediates effects of meaning in life, perfectionism, and self-esteem on psychological distress in Turkish adults. Australian Psychologist, 60(3), 235-247. https://doi.org/10.1080/00050067.2024.2415068

Li, C., Fu, P., Wang, M., Xia, Y., Hu, C., Liu, M., Zhang, H., Sheng, X., & Yang, Y. (2023). The role of self-esteem and emotion regulation in the associations between childhood trauma and mental health in adulthood: A moderated mediation model. BMC Psychiatry, 23(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04719-7

Li, W., & Lu, C. (2023). Reciprocal relationships between self-esteem, coping styles and anxiety symptoms among adolescents: Between-person and within-person effects. European Psychiatry, 66(S1), S748-S748. https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2023.1573

Lee, D. A., Scragg, P., & Turner, S. (2001). The role of shame and guilt in traumatic events: A clinical model of shame‐based and guilt‐based PTSD. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 74(4), 451-466. https://doi.org/10.1348/000711201161109

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2010). Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. Guilford Publications.

Miyamoto, Y., & Ma, X. (2011). Dampening or savoring positive emotions: A dialectical cultural script guides emotion regulation. Emotion, 11(6), 1346-1357. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025135

Murray, H., Pethania, Y., & Medin, E. (2021). Survivor Guilt: A Cognitive Approach. Cognitive behaviour therapist, 14, e28. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1754470X21000246

Norem, J. K., & Chang, E. C. (2002). The positive psychology of negative thinking. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(9), 993-1001. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.10094

Quoidbach, J., Berry, E. V., Hansenne, M., & Mikolajczak, M. (2010). Positive emotion regulation and well-being: Comparing the impact of eight savoring and dampening strategies. Personality and Individual Differences, 49(5), 368-373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.03.048

Slemp, G. R., & Vella-Brodrick, D. A. (2013). Optimising employee mental health: The relationship between intrinsic need satisfaction, job crafting, and employee well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(4), 957-977. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9458-3

Uchida, Y., Norasakkunkit, V., & Kitayama, S. (2004). Cultural constructions of happiness: Theory and emprical evidence. Journal of Happiness Studies, 5(3), 223-239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-004-8785-9

Vaish, A., Grossmann, T., & Woodward, A. (2008). Not all emotions are created equal: the negativity bias in social-emotional development. Psychological bulletin, 134(3), 383–403. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.134.3.383

Vassilopoulos, S. P. (2008). Coping strategies and anticipatory processing in high and low socially anxious individuals. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 22(1), 98-107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.01.010

Werner-Seidler, A., Banks, R., Dunn, B. D., & Moulds, M. L. (2013). An investigation of the relationship between positive affect regulation and depression. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 51(1), 46-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2012.11.001

Wood, J. V., Heimpel, S. A., & Michela, J. L. (2003). Savoring versus dampening: Self-esteem differences in regulating positive affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(3), 566-580. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.3.566

Zhang, H., Kahriz, B. M., McCabe, C., & Vogt, J. (2024). How to be happy from east to west: Social and flexible pursuit of happiness is associated with positive effects of valuing happiness on well-being. Current Psychology, 43(48), 36600-36616. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-07007-z

External links

- Cherophobia: Is being too happy a thing? (Healthline)

- What Is Cherophobia? How to Overcome a Fear of Happiness (Positive Psychology)

- Why You Don't "Deserve" to be Happy (Psychology Today)

- Here's The Deal with Survivor's Guilt (YouTube)

- The Fear of Happiness (YouTube)