Indian Shipping/Book 2/Chapter 3

CHAPTER III.

The Mogul Period (continued): From the Reign of Akbar to that of Aurangzeb.

We have now given an account of the development of Indian shipping and shipbuilding in the reign of Akbar and of the contributions made to it not only by his Government but also by private efforts, by independent Hindu and Mahomedan rulers. Nor was this development checked after Akbar's death, but continued through successive reigns.

After the death of Akbar in 1605, Islam Khan, Governor of Bengal, transferred the seat of government from Rajmahal to Dacca, and increased the Nowwara, or fleet, and artillery, which had been established in the time of Akbar in order to check the renewed aggressions of the Afghans and Maggs. As stated in the contemporary Persian account of Shihab-ud-din Talish, "in Jahangir's reign the Magg pirates used to come to Dacca for plunder and abduction, and in fact considered the whole of Bengal as their jaigir."[1] Islam Khan shortly afterwards defeated the combined forces of the Rajah of Arrakan and the Portuguese pirate Sebastian Gonzales, then in possession of Sandwipa, and commanding an army of 1,000 Portuguese, 2,000 sepoys, 200 cavalry, and 80 well-armed vessels of different sizes, who both made a descent upon the southern part of the province, laying waste the country along the eastern bank of the Megna.

In the reign of Shah Jahan, in a.d. 1638, there began a trouble from a new quarter. Even during the closing years of Akbar's reign, the tribes on the eastern frontier of Bengal, belonging to Kuch Behar and Assam, began to cause trouble. In a.d. 1596 an expedition was sent against Lachmi Narayan, the ruler of Kuch Behar, who commanded a large army consisting of 4,000 horse, 200,000 foot, 700 elephants, and a fleet of 1,000 ships (Akbarnāma). In 1600 an imperial fleet consisting of 500 ships was sent to encounter the fleet of Parichat, ruler of Kuch Hajo, in the Gujadhar river, who was defeated and taken prisoner (Padishanāma). But Baldeo, brother of Parichat, fled to Assam, and having collected an army of Kochis and Assamese, attacked the imperial army, as well as a fleet of nearly 500 ships, and defeated the whole force.[2] At last, in 1638, the Assamese themselves made a hostile descent on Bengal from their boats, sailing down the river Brahmaputra, and had almost reached Dacca when they were met by the Governor of Bengal, Islam Khan Mushedy, with the Nowwara. An engagement ensued in which 4,000 of them were slain and fifteen of their boats fell into the hands of the Mogul Government. The Maggs also were continuing their depredations in the southern parts of the district. "The established rental of the country was at this time almost entirely absorbed in jaigirs assigned to protect the coasts from their ravages, and such was the reduced state of the revenues that Fedai Khan obtained the government on condition of paying ten lacs of rupees a year; viz., five lacs to the Emperor and the same sum to Noor Jehan Begum in lieu of the imperial dues; while, on the invasion of the Assamese, it is said that not a single rupee was remitted to Delhi." Matters instead of improving became worse and worse owing to the continued dilapidation of the Bengal fleet on the one hand and the growing power of the Magg and Feringi fleets on the other. When, in a.d. 1639, Prince Shuja was appointed viceroy, "great confusion was caused by his negligence, and the extortion and violence of the clerks (mutasaddis) ruined the pargannahs assigned for maintaining the Nowwarrah (fleet). Many (naval) officers and workmen holding jagir or stipend were overpowered by poverty and starvation."

In the reign of Aurangzeb, when Mir Jumla came to Bengal as viceroy in 1660, removing the seat of government again to Dacca, he began "to make a new arrangement of the expenditure and tankhah of the flotilla, which amounted to fourteen lacs of rupees."[3] With a view to guarding against an invasion from Arrakan, Mir Jumla built several forts about the confluence of the Luckia and Issamutty, and constructed several good military roads and bridges in the vicinity of the town.[4] In 1661 Mir Jumla marched against Kuch Behar, and easily annexed the kingdom, when the Raja Bhim Narain fled. In the following year (1662) he embarked on his conquest of Assam with a large force consisting of infantry and artillery and the Nowwara. About 800 hostile ships attacked the imperial fleet, the cannonade lasting the whole night. The Nawab sent Muhammad Munim Beg to assist the fleet. This decided the fate of the engagement, resulting in the capture of 300 or 400 ships of the enemy with a gun on each. The Assamese burnt some 1,000 and odd ships, many of which were large enough to accommodate 80, 70, and 60 sailors, including 123 bachhari ships, like which no other existed in the dockyard at Ghargaon. The imperial fleet used in the engagement consisted of 323 ships, viz.:—

Kosahs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

159 | |

Jalbahs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

48 | |

Ghrabs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

10 | |

Parindahs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

7 | |

Bajrahs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

4 | |

Patilahs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

50 | |

Salbs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

2 | |

Patils . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

1 | |

Bhars . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

1 | |

Balams . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

1 | |

Rhatgiris . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

10 | |

Mahalgiris . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

5 | |

Palwarahs and other small ships . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

24 | |

Total . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

323323[5] | |

It was after all a pyrrhic victory, for a terrible sickness spread among the troops, carrying off many naval officers and men, including Mir Jumla himself. At the death of Mir Jumla, the Bengal flotilla was utterly ruined, and, taking advantage of this, the pirates, early in the year 1664, appeared Defore Dacca, "and defeated Munawwar Khan, Zemindar, who was stationed there with the relics of the Nowwara—a few broken and rotten boats—and bore the high title of Cruising Admiral (Sardar-i-Sairal)," and "the few boats that still belonged to the Nowwara were thus lost, and its name alone remained in Bengal." In 1664 Shaista Khan became viceroy; and resolving to suppress piracy at any cost, devoted all his energy to the rebuilding of the flotilla and the creation of a new one. The contemporary Persian manuscript of the Bodleian Library gives some interesting details regarding the means adopted by Shaista Khan to revive the Nowwara. "As timber and shipwrights were required for repairing and fitting out the ships, to every mauza of the province that had timber and carpenters bailiffs were sent with warrants to take them to Dacca." The principal centres of shipbuilding at that time appear to have been Hugli, Baleswar, Murang, Chilmari, Jessore and Karibari, where "as many boats were ordered to be built and sent to Dacca as possible." At headquarters, too, Shaista Khan did not for a moment "forget to mature plans for assembling the crew, providing their rations and needments, and collecting the materials for shipbuilding and shipwrights. Hakim Mahammad Hussain, mansabdar, an old, able, learned, trustworthy, and virtuous servant of the Nawab, was appointed head of the shipbuilding department. … To all ports of this department expert officers were appointed. Kishore Das, a well-informed and experienced clerk, was appointed to have charge of the pargannahs of the Nowwara and the stipend of the jaigirs assigned to the naval officers and men." As a result of this activity and the ceaseless exertions of the Nawab, we find the magnificent output of as many as 300 ships built in a very short time and equipped with the necessary materials.

To secure bases for the war against the Feringis of Chatgaon, the Nawab posted an officer with 200 ships at Sańgrāmgara, where the Ganges and the Brahmaputra unite, and another at Dhapa, with 100 ships, to help the former when required. Then the island of Sandwipa was conquered by defeating Dilawwar, a runaway ship-captain of Jahangir's time. At this time a section of the Feringis under their leader, Captain Moor, deserted to the Mogul side. The imperial fleet was placed under Ibn Hussain. It consisted of 288 ships, as described below:—

Ghrabs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

21 | |

Salb . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

3 | |

Kusa . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

157 | |

Jalba . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

96 | |

Bachhari . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

2 | |

Parenda . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

6 | |

Not specified . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

6 | |

Total . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

288 | |

Ibn Hussain advanced with the Nowwara by the sea in co-operation with the army advancing by land, the Nawab himself arranging to supply the expeditionary force constantly with provisions. The first naval battle was fought on a stormy sea. The Arrakanese were put to flight and ten ghrabs captured. The two fleets, with larger ships, again faced each other, and spent the night in distant cannonade. In the morning the imperial fleet advanced towards the enemy, with sails in the first line, then the gharabs, and last the jalbas and kusas side by side. The Arrakanese retreated into the Carnafuli river. The Moguls closed its mouth and then attacked and captured the Arrakanese navy, consisting of 135 ships, viz.:—

Khalu . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

2 | |

Ghrab . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

9 | |

Jangi . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

22 | |

Kusa . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

12 | |

Jalba . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

6767 (68?) | |

Balam . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

22 | |

Besides Bengal there were other parts of India in the time of Aurangzeb in which there was a marked development of Indian shipping and maritime commerce. Thomas Bowrey,[6] an English traveller to India during a.d. 1669-1679, has left a very valuable account of countries round the Bay of Bengal, in which are given descriptions and representations of ships and boats, which are "among the best of the kind for this period." The great trading and shipping centre of the time on the Coromandel coast was Metchlepatam (Masulipatam), of which the inhabitants "are great merchant adventurers, and transport vast stocks in the goods aforesaid, both in their own ships as also upon fraught in English ships or vessels." Among the miscellaneous papers at the end of the Diary of Strenysham Master there is, pp. 337-339, an "Account of the trade of Metchlepatam," by Christopher Hotton, dated 9th Jan. 1676-77. He says: "Arriving first in 1657, at which time I found this place in a very flourishing condition, 20 sail of ships of burden belonging to the native inhabitants here constantly employed on voyages to Arracan, Pegu, Tanassery, Queda, Malacca, … Moca, Persia, and the Maldive Islands."

The King of Golconda also had a mercantile marine. He had several ships "that trade yearly to Arrakan, Tenassery, and Ceylon to purchase elephants for him and his nobility. They bring in some of his ships from fourteen to twenty-five of these vast creatures. They must of necessity be of very considerable burthens and built exceeding strong." Bowrey also saw a ship belonging to the King of Golconda, built for the trade to Mocha in the Red Sea, "which could not be, in my judgment, less than 1,000 tons in burden."[7]

Narsapore, 45 miles north of Masulipatam, was also one of the important shipping centres. It "aboundeth well in timber and conveniences for the building and repairing ships" (p. 99). Morris, in his Godavari District, says, "the place was well known more than two centuries ago for its docks for the building and repair of large vessels." In a "Generall" from Balasor, dated 16 December, 1670, the Factors at the Bay wrote to the Court (Factory Records, Misc. no. 3) that they had ordered a ship to be built at "Massapore" in place of the "Madras Pinnace"; they added, "We should ourselves have built another but that neither timber nor workmen are so good as at Massapore."[8]

Madapollum was another shipping centre where "many English merchants and others have their ships and vessels yearly built. Here is the best and well-grown timber in sufficient plenty, the best iron upon the coast; any sort of iron-work is here ingeniously performed by the natives, as spikes, bolts, anchors, and the like. Very expert master-builders there are several here; they build very well, and launch with as much discretion as I have seen in any part of the world. They have an excellent way of making shrouds, stays, or any other rigging for ships."[9]

Bowrey refers to a sort of "ship-money" imposed by Nawab Shaista Khan of Bengal on the mercantile community to build up the naval defence or power of the country. Thus, not satisfied that all, both rich and poor, should bow to him, but wishing the ships upon the water should do the like, the Nawab would every year send down to the merchants in Hugli, Jessore, Pipli, and Balasore for a ship or two in each respective place of 400, 500, or 600 tons, to be very well built and fitted, even as if they were to voyage to sea, as also 10, 20, or 30 galleys for to attend them, the Moor's governors having strict orders to see them finished with all speed, and gunned and well manned, and sent up the Ganges as high as Dacca.[10]

Of the Nawab's mercantile marine Bowrey says that it consists of about "20 sail of ships of considerable burden that annually trade to sea from Dacca, Balasore, and Pipli, some to Ceylon, some to Tenessarim. These fetch elephants, and the rest, 6 or 7, yearly go to the Twelve Thousand Islands, called the Maldives, to fetch cowries and cayre (coir), and most commonly do make profitable voyages."[11]

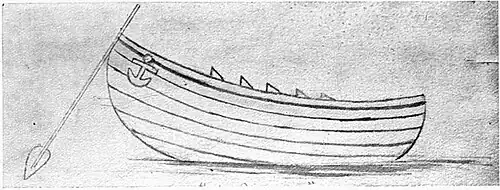

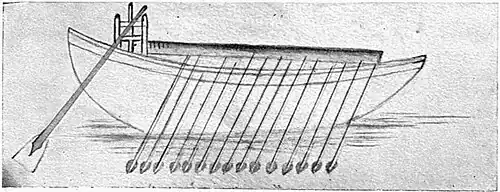

Lastly, Bowrey gives an account of the various kinds of ships and boats that were then built. The Massoola boats, used in lading and unlading ships or vessels, "are built very slight, having no timbers in them save 'thafts' to hold their sides together. Their planks are very broad and thin, sewed together with coir; they are flat-bottomed" and most proper for the Coromandel coast; for "all along the shore the sea runneth high and breaketh, to which they do buckle and also to the ground where they

A PATELLA.

AN OLOAKO.

A BUDGAROO. strike."[12] There is another kind of boat called the catamaran, made of four, five, or six large pieces of buoyant timber "upon which they can lade three or four tons of weight." In Bengal, Bowrey noticed "great flat-bottomed vessels of an exceeding strength which are called Patellas and built very strong. Each of them will bring down 4,000, 5,000, or 6,000 Bengal maunds." Bowrey also mentions several sorts of boats that were in use on rivers. The Oloako boats are rowed some with four, some with six oars, and ply for a fare. A Budgaroo, a pleasure boat, was used by the upper classes. A Bajra was a kind of large boat, fairly clean, the centre of which formed a little room. The Purgoos which were seen for the most part between Hugli, Piplo, and Balesore were used for lading and unlading ships. "They will live a long time in the sea, being brought to anchor by the sterne, as their usual way is." Booras were "very floaty, light boats, rowing with twenty or thirty oars. These carry salt, pepper, and other goods from Hugli downwards, and some trade to Dacca with salt; they also serve for tow-boats for the ships bound up or down the river." Lastly, there were the "men-of-war prows" which were used in the Malaya Archipelago.[13]

Dr. Fryer, who visited India about the year 1674, has also left some interesting details about Indian ships and boats. He describes the Mussoola as "a boat wherein ten men paddle, the two aftermost of whom are the steersmen, using their paddles instead of rudder: the boat is not strengthened with knee-timber, as ours are; the bended planks are sewed together with rope-yarn of the cocoe and caulked with dammar (a sort of rosin taken out of the sea) so artificially that it yields to every ambitious surf."[14] He describes catamarans as formed of "logs lashed to that advantage that they waft all their goods, only having a sail in their midst, and paddles to guide them." Dr. Fryer was landed at Masulipatam by one of the country boats, which he describes as being "as large as one of our ware-barges and almost of that mould, sailing with one sail like them, but paddling with paddles instead of spreads, and carry a great burden with little trouble; outliving either ship or English skiff over the bar."

On the west coast also there were important

A PURGOO.

A BOORA.

MAN-OF-WAR PROW. shipping centres in Aurangzeb's time. According to Dr. Fryer (1672) Aurangzeb had at Surat four great ships always in pay to carry pilgrims to Mecca free of cost. These vessels were "huge, unshapen things." He also noticed at Surat some Indian ships or merchantmen carrying thirty or forty pieces of cannon, and "three or four men-of-war as big as third-rate ships, "as also frigates fit to row or sail, made with prows instead of beaks, more useful in rivers and creeks than in the main." The captain of a ship was called Nacquedah (Pers. nakhuda, ship-master) and the boatswain Tindal. Some of the larger Indian ships at Surat, of which the names are also known, fell a prey to the pirates that infested the whole of the western coast, and became a terrible scourge to the Indian trade in the time of the Emperor Aurangzeb, just as their brethren on the west coast, the Magg and Feringhi pirates, were harrying deltaic Bengal. Thus in August, 1691, a ship belonging to Abdul Guffoor, who was the wealthiest and most influential merchant in Surat, was captured by pirates at the mouth of the Surat river with nine lacs in hard cash on board. Soon afterwards another ship, named Futteh Mahmood, with a valuable cargo, also belonging to Abdul Guffoor, was similarly seized by an Englishman called Every, who was the most notorious pirate of the time. A few days after the capture of the Futteh Mahmood, Every took off Sanjan, north of Bombay, a ship belonging to the Emperor Aurangzeb himself, called the Gunj Suwaie ("exceeding treasure"). According to Khafi Khan, the historian, the Gunj Suwaie was the largest ship belonging to the port of Surat. She carried eight guns and four hundred matchlocks, and was deemed so strong that she disdained the help of a convoy. She was annually sent to Mecca, carrying Indian goods to Mocha and Jedda. She was returning to Surat with the result of the season's trading, amounting to fifty-two lacs of rupees in silver and gold, with Ibrahim Khan as her captain, and when she had come within eight or nine days from Surat she was attacked and seized by the English pirate "sailing in a ship of much smaller size, and nothing a third or fourth of the armament." Another capture of Every was the Rampura, a Cambay ship with a cargo valued at Rs. 1,70,000. Shivaji also, as we shall presently see, used to intercept these Mogul ships plying between Surat and Mecca by means of the fleet which he fitted out at his ports built on the coasts.[15]

During the same period a great impetus to Indian shipping and maritime enterprise was given by the great Mahratta leader, Śivaji,[16] who liberally patronized the shipbuilding industry. The growth of the Mahratta power was accompanied by the formation of a formidable fleet. Several docks were built, such as those in the harbours of Vijayadoorga, Kolaba, Sindhuvarga, Ratnagiri, Anjanvela, and the like, where men-of-war were constructed.[17] In 1698, Conajee Angria succeeded to the command of the Mahratta navy with the title of Darya-Saranga. The career of Angria was one long series of naval exploits and achievements rare in the annals of Indian maritime activity, but unfortunately "dismissed in a few words by our Indian historians."[18] Under him the Mahratta naval power reached its high-water mark. Bombay had to wage a long half-century of amateur warfare to subdue the Angrian power. It would be tedious to relate all the details of their long-continued conflict, but we may mention some of the more important events. In the name of the Satara chief, Angria was master of the whole coast from Bombay to Vingorla, and, with a fleet of armed vessels carrying thirty and forty guns apiece, he soon became a menace to the European trade of the west coast. In 1707 his ship attacked the Bombay frigate, which was blown up after a brief engagement. In 1710 he seized and fortified Kanhery, and his ships fought the Godolphin for two days. In 1712 he captured the Governor of Bombay's armed yacht, and fought two East Indiamen bound for Bombay. In 1716 he made prize of four private ships from Mahim, an East Indiaman named Success, and a Bengal ship named Otter. Then followed, successively, expeditions against Gheriah, Kanhery, and Colaba, which all proved abortive and ineffectual against the power of the Angrian fleet. In 1729 Conajee Angria died, and was succeeded at Severndoorg by Sambhuji Angria, who carried on his predatory policy for nearly thirty years. In 1730 the Angrian squadron of four grabs and fifteen gallivats destroyed the galleys Bombay and Bengal off Colaba. In 1732, five grabs and three gallivats attacked the East Indiaman Ockham. In 1735 a valuable East Indiaman named the Derby, with a great cargo of naval stores, fell into Sambhuji's hands. In 1738 a Dutch squadron of seven ships-of-war and seven sloops was repulsed from Gherriah. In 1740 some fifteen sail of Angria's fleet gave battle to four ships returning from China. The same year Sambhuji attacked Colaba with his army and forty or fifty gallivats, but was opposed by the English. In 1743 Sambhuji died, leaving his predatory policy to be continued by his successor, Toolaji. His greatest success was achieved in 1749, when Toolaji's fleet of five grabs and a swarm of gallivats surrounded and cannonaded the Restoration, the most efficient ship of the Bombay Marine. "Toolajee had now become very powerful. From Cutch to Cochin his vessels swept the coast in greater numbers than Conajee had ever shown. The superior sailing powers of the Mahratta vessels enabled them to keep out of range of the big guns, while they snatched prizes within sight of the men-of-war." In 1754 the Dutch suffered a severe loss at Toolaji's hands, losing a vessel loaded with ammunition, and two large ships. The next year the English and Peshwa formed an alliance against him, and jointly attacked Severndoorg, which was reduced after forty-eight hours' fighting. Then followed the well-planned expedition led by Admiral Watson and Clive against Gherriah, resulting in the burning of the Angrian fleet, consisting of "three three-masted ships carrying twenty guns each, nine two-masted carrying from twelve to sixteen guns, thirteen gallivats carrying from six to ten guns, thirty others unclassed, two on the stocks, one of them pierced for forty guns." The following is a very interesting description by an eye-witness of Angria's fleet: "His fleet consisted of grabs and gallivats. … The grabs have rarely more than two masts. … They are very broad in proportion to their length. … On the main deck under the forecastle are mounted two pieces of cannon of nine or twelve pounders, which point forwards through the portholes cut in the bulkhead and fire over the prow; the cannon of the broadside are from six to nine pounders. The gallivats are large row-boats rarely exceeding seventy tons. The gallivats are covered with a spar deck, made for lightness of split bamboos, and these only carry pettera roes, which are fixed on swivels in the gunnel of the vessel: but those of the largest size have a fixed deck on which they mount six or eight pieces of cannon, from two to four pounders. They have forty or fifty stout oars, and may be rowed four miles an hour. Eight or ten grabs and forty or fifty gallivats, crowded with men, generally composed Angria's principal fleet, destined to attack ships of force or burthen."[19] The fall of Gherriah meant the extinction of Mahratta naval power, which had been the terror of the coast for a whole half-century.

"MAHRATTA GRABS AND GALLIVATS ATTACKING AN ENGLISH SHIP."

(From the picture in the possession of Sir Ernest Robinson.)

- ↑ J.A.S.B., vol. iii., N.S., pp. 424, 425.

- ↑ J.A.S.B., 1872, Part i., No. 1, pp. 64 ff.

- ↑ MS. Bodleian 598, in J.A.S.B., June, 1907.

- ↑ Taylor's Topography and Statistics of Dacca, p. 76.

- ↑ Fathiyyah-i-ibriyyah, translated by Blochmann in the J.A.S.B., 1872, Part i., No. 1, pp. 64-96.

- ↑ A Geographical Account of Countries round the Bay of Bengal, 1669-1675, by Thomas Bowrey, edited by Lieut.-Colonel Sir Richard Carnac Temple, Bart., C.I.E., Series II., vol. xii. (Hakluyt Society publication).

- ↑ A Geographical Account of Countries round the Bay of Bengal, pp. 72 ff.

- ↑ A Geographical Account of Countries round the Bay of Bengal, pp. 72 ff.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 100-5.

- ↑ Geographical Account of Countries round the Bay of Bengal, pp. 179-80.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ A Geographical Account of Countries round the Bay of Bengal, p. 43.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Early Records of British India, by J. T. Wheeler, p. 54. Major H. Bevan in his Thirty Years in India (1808-1838), p. 14, vol. i., speaks of the Masula boat as "admirably contrived to resist the impetus of the surf in the roadstead of Madras. It is built of planks of wood sewed together with sun, a species of twine, and caulked with coarse grass, not a particle of iron being used in the entire construction. Both ends are sharp, narrow, and tapering to a point so as easily to penetrate the surf." Bevan also remarks, "The build of the boats all along the coast of India varies according to the localities for which they are destined, and each is peculiarly adapted to the nature of the coast on which it is used."

- ↑ Early Records of British India, by J. T. Wheeler; The Pirates of Malabar, by Colonel J. Biddulph.

- ↑ Cf. Duff's History of the Mahrattas, p. 85: "Having seen the advantage … derived from a fleet Śivaji used great exertions to fit out a marine. He rebuilt or strengthened Kolaba, repaired Severndroog and Viziadroog, and prepared vessels at all these places. His principal depot was the harbour of Kolaba, twenty miles south of Bombay." Also, "History of the Konkan" in the Bombay Gazetteer, vol. i., Part ii., pp. 68 foll.: "Shivaji caused a survey to be made of the coast, and having fixed on Malvan as the best protection for his vessels and the likeliest place for a stronghold, he built forts there, rebuilt and strengthened Suvarndurg, Ratnagiri, Jaygad, Anjanabel, Vijiaydurg, and Kolaba, and prepared vessels at all these places."

- ↑ Cf. Duff's History of the Mahrattas, pp. 172: "The Mahrattas continued in possession of most of their forts on the coast; they had maritime depots at Severndroog and Viziadroog, but the principal rendezvous of their fleet continued, as in the time of Shivaji, at Kolaba."

- ↑ Col. Biddulph in The Pirates of Malabar.

- ↑ Bombay Gazetteer, vol. i., Part ii., p. 89.