Staphylococcal enteritis

| Staphylococcal enteritis | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Staphylococcal food poisoning[1] | |

| |

| |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Nausea,vomiting, abdominal cramping,headache[3] |

| Causes | Staphylococcal enterotoxins[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Stool sample, based on symptoms[3] |

| Differential diagnosis | Clostridium difficile infection[3] |

| Prevention | Handwashing[1] |

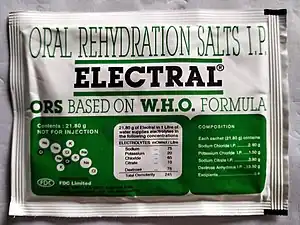

| Treatment | Electrolyte replacement[3] |

Staphylococcal enteritis is an inflammation that is usually caused by eating or drinking substances contaminated with staph enterotoxin. The toxin, not the bacterium, settles in the small intestine and causes inflammation and swelling. This in turn can cause abdominal pain, cramping, dehydration, diarrhea and fever.[4][3][5]

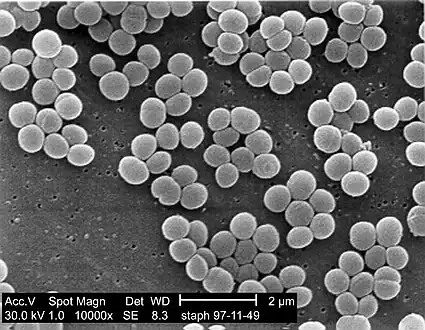

Staphylococcus aureus is a Gram-positive, facultative anaerobe, coccal (round shaped) bacteria that appears in grape-like clusters that can thrive in high salt and low water activity habitats. S. aureus bacteria can live on the skin which is one of the primary modes of transmission. S. aureus can cause a range of illnesses from minor skin infections to Staphylococcus aureus food poisoning enteritis. Since humans are the primary source, cross-contamination is the most common way the microorganism is introduced into foods. Foods at high risks are those prepared in large quantities. Staphylococcus aureus is a true food poisoning organism. It produces a heat stable enterotoxin when allowed to grow for several hours in foods such as cream-filled baked goods, poultry meat, gravies, eggs, meat salads, puddings and vegetables. It is important to note that the toxins may be present in dangerous amounts in foods that have no signs of spoilage, such as a bad smell, any off color, odor, or textural or flavor change.[6][7]

Enteritis is the inflammation of the small intestine. It is generally caused by eating or drinking substances that are contaminated with bacteria or viruses. The bacterium and/or toxin settles in the small intestine and cause inflammation and swelling. This in turn can cause abdominal pain, cramping, diarrhea, fever, and dehydration. There are other types of enteritis, the types include: bacterial gastroenteritis, Campylobacter enteritis, E. coli enteritis, radiation enteritis, Salmonella enteritis and Shigella enteritis.[8][9]

Symptoms and signs

Common symptoms of Staphylococcus aureus food poisoning include: a rapid onset which is usually 1–6 hours, nausea, explosive vomiting for up to 24 hours, abdominal cramps/pain, headache, weakness, diarrhea and usually a subnormal body temperature. Symptoms usually start one to six hours after eating and last less than 12 hours. The duration of some cases may take two or more days to fully resolve.[10]

Complications

As to the possible complications of Staphylococcal enteritis we find:[11][12]

- Severe dehydration

- Low blood pressure(shock)

- Secondary infections

Cause

Staphylococcal enterotoxins are toxins produced by Staphylococcus aureus, a type of bacteria. These enterotoxins, such as Staphylococcal Enterotoxin B , are known for causing food poisoning and toxic shock syndrome[13][14]

Pathogenesis

.webp.png)

S. aureus is an enterotoxin producer. Enterotoxins are chromosomally encoded exotoxins that are produced and secreted from several bacterial organisms. It is a heat stable toxin and is resistant to digestive protease.[15][16] [17]

It is the ingestion of the toxin that causes the inflammation and swelling of the intestine.[17]

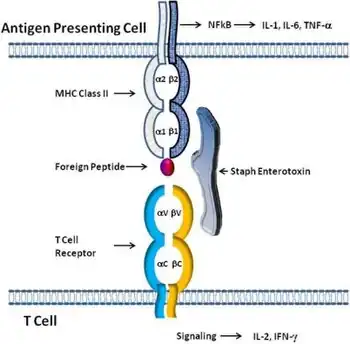

Staphylococcal enterotoxins are potent superantigens. Unlike conventional antigens that require specific processing and presentation to T-cells, superantigens directly bind to the major histocompatibility complex molecules on antigen-presenting cells and the T-cell receptor without the need for specific antigen recognition. This bypasses normal immune regulation, leading to the activation and proliferation of a large, non-specific population of T-cells[17][18]

This widespread T-cell activation triggers a massive release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-2 and interferon-gamma. This cytokine storm is responsible for many of the systemic symptoms[19][20]

Diagnosis

For the detection of Staphylococcus aureus food poisoning which can lead to staphylococcal enteritis a stool culture may be required. A stool culture is used to detect the presence of disease-causing bacteria (pathogenic) and help diagnose an infection of the digestive tract. In the case of staphylococcal enteritis, it is conducted to see if the stool is positive for a pathogenic bacterium.[21][8][22]

Differential diagnosis

As to the DDx in an affected individual we find the following:[3][23]

- Viral gastroenteritis

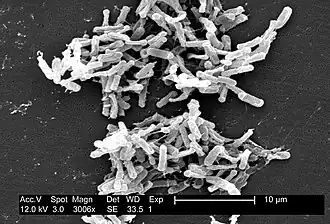

- Clostridium difficile infection

- Parasitic infections

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Ischemic enteritis

Prevention

Staphylococcal enteritis may be avoided by using proper hygiene and sanitation with food preparation. This includes thoroughly cooking all meats. If food is to be stored longer than two hours, keep hot foods hot (over 140 °F) and cold foods cold (40 °F or under).[16] Ensure to refrigerate leftovers promptly and store cooked food in a wide, shallow container and refrigerate as soon as possible. Sanitation is very important, keep kitchens and food-serving areas clean and sanitized. Finally, as most staphylococcal food poisoning are the result of food handling, hand washing is critical. Food handlers should use hand sanitizers with alcohol or thorough hand washing with soap and water.[24][1]

Treatment

Treatment is supportive and based upon symptoms, with fluid and electrolyte replacement as the primary goal. Dehydration caused by diarrhea and vomiting is the most common complication. To prevent dehydration, it is important to take frequent sips of a rehydration drink (like water) or try to drink a cup of water or rehydration drink for each large, loose stool.[25]

Dietary management of enteritis consists of starting with a clear liquid diet until vomiting and diarrhea end and then slowly introduce solid foods. [8]

Epidemiology

In terms of the incidence we find that Staphylococcal food poisoning is one of the most frequent occurring foodborne illnesses. The bacteria thrive in environments with high salt concentrations and low water activity, making certain foods susceptible. Acute gastroenteritis(due to cases due to Staphylococcus aureus), leads to millions of illnesses each year[26]

History

As to history we find that Staphylococcal enteritis is an inflammation caused by eating/drinking substances contaminated with staph enterotoxin, which in turn was identified in the year 1881 as a cause of infection by Scottish surgeon Sir Alexander Ogston[27]

In the mid-20th century, outbreaks of staphylococcal enteritis were documented, particularly in hospital settings where antibiotic use disrupted gut flora[28]

Research

As to recent research shows that probiotics can act as a natural defense. A recent clinical trial revealed that a probiotic containing Bacillus subtilis spores significantly reduced S. aureus colonization in the gut(and nose) by 97 percent in stool samples(and 65 percent in nasal samples).[29]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "Preventing Staphylococcal (Staph) Food Poisoning". Staphylococcal Food Poisoning. 21 May 2024. Retrieved 7 June 2025.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Pinchuk, Irina V.; Beswick, Ellen J.; Reyes, Victor E. (August 2010). "Staphylococcal Enterotoxins". Toxins. 2 (8): 2177–2197. doi:10.3390/toxins2082177. ISSN 2072-6651. PMID 22069679.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 "Staphylococcal Food Poisoning - Gastrointestinal Disorders". Merck Manual Professional Edition. Archived from the original on 2 July 2025. Retrieved 28 May 2025.

- ↑ Bergdoll, M. S.; Wong, A. L. (1 January 2003). "STAPHYLOCOCCUS | Food Poisoning". Encyclopedia of Food Sciences and Nutrition (Second ed.). Academic Press. pp. 5556–5561. ISBN 978-0-12-227055-0.

- ↑ "Bacterial gastroenteritis: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Archived from the original on 18 March 2025. Retrieved 9 June 2025.

- ↑ "Disease Listing, Staphylococcal Food Poisoning, General Info CDC Bacterial, Mycotic Diseases". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 29 March 2006. Archived from the original on 2 April 2016. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- ↑ "BBB - Staphylococcus aureus". US Food and Drug Administration. 4 May 2009. Archived from the original on 9 April 2020. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 "Enteritis: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Archived from the original on 5 July 2016. Retrieved 8 June 2025.

- ↑ Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2 May 2011. ISBN 978-1-4160-6257-8.

- ↑ "Enteritis - PubMed Health". National Center for Biotechnology Information. 12 April 2010. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- ↑ "Symptoms of Food Poisoning". Food Safety. 31 January 2025. Archived from the original on 24 May 2025. Retrieved 30 May 2025.

- ↑ "Staphylococcal Food Poisoning - Digestive Disorders". Merck Manual Consumer Version. Archived from the original on 27 June 2025. Retrieved 30 May 2025.

- ↑ Moran, Gregory J.; Talan, David A.; Abrahamian, Fredrick M. (1 March 2008). "Biological Terrorism". Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 22 (1): 145–187. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2007.12.003. ISSN 0891-5520. PMC 7126662. PMID 18295687.

- ↑ Fries, Bettina C.; Varshney, Avanish K. (December 2013). "Bacterial Toxins-Staphylococcal Enterotoxin B". Microbiology Spectrum. 1 (2): 10.1128/microbiolspec.AID–0002–2012. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.AID-0002-2012. ISSN 2165-0497. PMC 5086421. PMID 26184960.

- ↑ Vesterlund, S. (1 June 2006). "Staphylococcus aureus adheres to human intestinal mucus but can be displaced by certain lactic acid bacteria" (PDF). Microbiology. 152 (6): 1819–1826. doi:10.1099/mic.0.28522-0. PMID 16735744. Archived from the original on 11 December 2019. Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "CDC - Staphylococcal Food Poisoning - NCZVED". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 7 June 2010. Archived from the original on 19 December 2016. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Fisher, Emilie L.; Otto, Michael; Cheung, Gordon Y. C. (13 March 2018). "Basis of Virulence in Enterotoxin-Mediated Staphylococcal Food Poisoning". Frontiers in Microbiology. 9: 436. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.00436. ISSN 1664-302X. PMC 5890119. PMID 29662470.

- ↑ Proft, T; Fraser, J D (19 August 2003). "Bacterial superantigens". Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 133 (3): 299–306. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02203.x. PMID 12930353.

- ↑ Karki, Rajendra; Kanneganti, Thirumala-Devi (August 2021). "The 'cytokine storm': molecular mechanisms and therapeutic prospects". Trends in Immunology. 42 (8): 681–705. doi:10.1016/j.it.2021.06.001. ISSN 1471-4981. PMC 9310545. PMID 34217595.

- ↑ McCormick, John K.; Yarwood, Jeremy M.; Schlievert, Patrick M. (October 2001). "Toxic Shock Syndrome and Bacterial Superantigens: An Update". Annual Review of Microbiology. 55 (1): 77–104. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.77. PMID 11544350. Archived from the original on 2025-02-07. Retrieved 2025-06-05.

- ↑ Barr, Wendy; Smith, Andrew (1 February 2014). "Acute Diarrhea in Adults". American Family Physician. 89 (3): 180–189. Archived from the original on 9 July 2025. Retrieved 12 June 2025.

- ↑ Shane, Andi L.; Mody, Rajal K.; Crump, John A.; Tarr, Phillip I.; Steiner, Theodore S.; Kotloff, Karen; Langley, Joanne M.; Wanke, Christine; Warren, Cirle Alcantara; Cheng, Allen C.; Cantey, Joseph; Pickering, Larry K. (29 November 2017). "2017 Infectious Diseases Society of America Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Infectious Diarrhea". Clinical Infectious Diseases: An Official Publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 65 (12): 1963–1973. doi:10.1093/cid/cix959. ISSN 1537-6591. PMC 5848254. PMID 29194529.

- ↑ Meisenheimer, Erica S.; Epstein, Carly; Thiel, Derrick (July 2022). "Acute Diarrhea in Adults". American Family Physician. 106 (1): 72–80. ISSN 1532-0650. PMID 35839362.

- ↑ Lalla, F.; Dingle, P. (2004). "The efficacy of cleaning products on food industry surfaces". Journal of Environmental Health. 67 (2): 17–21. PMID 15468512.

- ↑ "Staphylocococcus aureus (food poisoning)". www.bccdc.ca. Archived from the original on 1 May 2025. Retrieved 7 June 2025.

- ↑ Schmidt, Mark A.; Groom, Holly C.; Rawlings, Andreea M.; Mattison, Claire P.; Salas, Suzanne B.; Burke, Rachel M.; Hallowell, Ben D.; Calderwood, Laura E.; Donald, Judy; Balachandran, Neha; Hall, Aron J. (November 2022). "Incidence, Etiology, and Healthcare Utilization for Acute Gastroenteritis in the Community, United States". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 28 (11): 2234–2242. doi:10.3201/eid2811.220247. PMC 9622243. PMID 36285882. Archived from the original on 2025-06-29. Retrieved 2025-06-03.

- ↑ Rennie, David A. (2024). Sir Alexander Ogston, 1844-1929: A Life at Medical and Military Frontlines. Edinburgh University Press. p. 168. ISBN 978-1-3995-0131-6. JSTOR 10.3366/jj.9941231.

- ↑ GARDNER, ROBERT J.; HENEGAR, GEORGE C.; PRESTON, FREDERICK W. (1 July 1963). "Staphylococcus Enterocolitis". Archives of Surgery. 87 (1): 58–64. doi:10.1001/archsurg.1963.01310130060008. ISSN 0004-0010. PMID 13946551. Archived from the original on 30 November 2024. Retrieved 9 June 2025.

- ↑ "Probiotic blocks staph bacteria from colonizing people | National Institutes of Health (NIH)". www.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 28 April 2025. Retrieved 24 August 2025.

Further reading

- Bonnie, M.; Friese, G. (2007). "A sickening situation: prehospital assessment and treatment of foodborne illnesses". EMS Magazine. 36 (9): 65–70. PMID 17910244.

- Cerrato, P. (1999). "When food is the culprit". RN. 62 (6): 52–58. PMID 10504994.

- Ingebretsen, R (2010). "Introduction to Wilderness Medicine. Salt Lake City: Wilderness Medicine of Utah". Wilderness Medicine - HEDU 5800. Archived from the original on 1 July 2013. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- Loir, YL; Baron, F.; Gautier, M. (31 March 2003). "Review Staphylococcus aureus and food poisoning". Genetics and Molecular Research. 2 (1): 63–76. PMID 12917803. Archived from the original on 2 May 2012. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- Okii, K.; Hiyama, E.; Takesue, Y.; Kodaira, M.; Sueda, T.; Yokoyama, T. (2006). "Molecular epidemiology of enteritis-causing methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus". Journal of Hospital Infection. 62 (1): 37–43. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2005.05.013. PMID 16216385.

- Olson, R.; Eidson, M.; Sewell, C. (1997). "Staphylococcal food poisoning from a fundraiser". Journal of Environmental Health. 60 (3): 7–11.

- Willey, J. M.; Sherwood, L.; Woolverton, C. J. (2011). Prescott, Harley, and Klein's Microbiology (8th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

External links

- "Foodborne Outbreaks". Foodborne Outbreaks CDC. 12 August 2025. Archived from the original on 25 August 2025. Retrieved 28 August 2025.

| Classification |

|---|