Ocular larva migrans

| Ocular larva migrans | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Ocular toxocariasis[1] | |

| |

| Specialty | Infectious disease, ophthalmology |

| Symptoms | Blurred vision, pain |

| Causes | Toxocara canis, others |

| Diagnostic method | Exam of eye,MRi |

| Treatment | Antiparasitic medication |

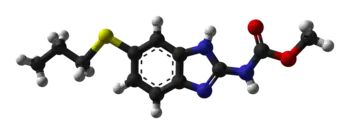

Ocular larva migrans (OLM), also known as ocular toxocariasis, is the ocular form of larva migrans syndrome. It occurs when roundworm larvae invade the human eye. OLM infections in humans are caused by the larvae of Toxocara canis (dog roundworm), Toxocara cati (feline roundworm), Ascaris suum (large roundworm of pig), or Baylisascaris procyonis (raccoon roundworm).[4]

They may be associated with visceral larva migrans. Unilateral visual disturbances, strabismus, and eye pain are the most common presenting symptoms.Blood tests to detect antibodies against Toxocara are used for diagnosis.Treatment can consist of antiparasitic medications(albendazole, mebendazole)[5]

Signs and symptoms

As to the presentation of Ocular larva migrans we find the following:[6]

- Unilateral vision loss

- Eye pain

Complications

The eye involvement can cause the following inflammatory disorders:

Cause

In terms of etiology, Ocular larva migrans is primarily caused by the species Toxocara canis, which is the most common cause, though there are others[4][5]

Mechanism

Ocular toxocariasis begins when humans ingest Toxocara eggs which then hatch in the intestine. These larvae penetrate the intestinal wall, enter the bloodstream, and migrate throughout the body eventually lodging in eye. In the eye the larva and its secreted antigens trigger a localized granulomatous inflammatory response from the immune system, which attempts to wall off the parasite. This inflammation leads to the formation of a mass on the retina, and results in associated complications - chronic inflammation, fibrosis, and tractional retinal detachment which are mechanisms that cause permanent vision loss[4]

Diagnosis

The disease presents with an eosinophilic granulomatous mass, most commonly in the posterior pole of the retina. The granulomatous mass develops around the entrapped larva, in an attempt to contain the spread of the larva.

ELISA testing of intraocular fluids has been demonstrated to be of great value in diagnosing ocular toxocariasis.

Differential diagnosis

In terms of the DDx for Ocular larva migrans we find the following :[4]

- Familial exudative vitreoretinopathy

- Retinal pigment epithelium

- SHAPU

- Endophthalmitis

- Retinopathy of prematurity

Management

As to treatment we find that the following is done in the affected individual:[4][5]

- Anti-helminthic therapy(Albendazole)

- Corticosteroids(topically, periocularly, intraocularly, or systemically)

- Laser photocoagulation

- Surgery

Epidemiology

Although systemic toxocariasis is common worldwide,with seroprevalence ranging from 4 to 31 percent in developed countries and up to 80 percent in tropical regions,ocular involvement is much less frequent, often underdiagnosed/misclassified as retinoblastoma[7]

History

As to history we find that Ocular Larva Migrans was first described by Wilder in 1950.She published a report on the ocular infection, identifying a nematode larva within retinal granulomas in enucleated eye specimens[4]

Research

A July 2025 study found that measuring intraocular fluid total IgE and the IF/serum IgE ratio improves diagnostic accuracy for ocular toxocariasis, especially in children who showed notably higher intraocular IgE levels than adults; this may indicate age-related immune differences [8]

References

- ↑ "Ocular toxocariasis (Concept Id: C0028848) - MedGen - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 31 October 2025.

- ↑ Ahn, Seong Joon; Woo, Se Joon; Jin, Yan; Chang, Yoon-Seok; Kim, Tae Wan; Ahn, Jeeyun; Heo, Jang Won; Yu, Hyeong Gon; Chung, Hum; Park, Kyu Hyung; Hong, Sung Tae (12 June 2014). "Clinical Features and Course of Ocular Toxocariasis in Adults". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 8 (6): e2938. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002938. ISSN 1935-2735. Archived from the original on 27 May 2024. Retrieved 31 October 2025.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ↑ Ahn, Seong Joon; Ryoo, Na-Kyung; Woo, Se Joon (July 2014). "Ocular toxocariasis: clinical features, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention". Asia Pacific Allergy. 4 (3): 134–141. doi:10.5415/apallergy.2014.4.3.134. ISSN 2233-8276. Archived from the original on 3 September 2025. Retrieved 8 November 2025.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Gupta, Abhishek; Tripathy, Koushik (2025). "Ocular Toxocariasis". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Archived from the original on 2024-04-30. Retrieved 2025-10-31.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 "Ocular Toxocariasis - Europe". American Academy of Ophthalmology. 13 October 2014. Retrieved 11 November 2025.

- ↑ "Toxocariasis - EyeWiki". eyewiki.org. Archived from the original on 11 October 2025. Retrieved 31 October 2025.

- ↑ "Ocular Toxocariasis - Asia Pacific". American Academy of Ophthalmology. 13 October 2014. Retrieved 13 November 2025.

- ↑ Zhang, Shuang; Chen, Li; Hu, Xiaofeng; Wang, Hui; Feng, Jing; Tao, Yong (28 July 2025). "Evaluation of the intraocular total IgE level and its ratio with serum IgE level for the diagnosis of ocular toxocariasis in children and adults: a retrospective comparative study". BMC Ophthalmology. 25 (1): 428. doi:10.1186/s12886-025-04252-z. ISSN 1471-2415.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)

Further reading

- Ahn, Seong Joon; Ryoo, Na-Kyung; Woo, Se Joon (July 2014). "Ocular toxocariasis: clinical features, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention". Asia Pacific Allergy. 4 (3): 134–141. doi:10.5415/apallergy.2014.4.3.134. ISSN 2233-8276.

- Pinelli, E. (2011). "Toxocara and Ascaris seropositivity among patients suspected of visceral and ocular larva migrans in the Netherlands: trends from 1998 to 2009". European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases. 30 (7): 873–879. doi:10.1007/s10096-011-1170-9. PMID 21365288.

- Liu, G (September 2015). "Baylisascaris procyonis and Herpes Simplex Virus 2 Coinfection Presenting as Ocular Larva Migrans with Granuloma Formation in a Child". American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 93 (3): 612–614. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.15-0272. PMC 4559706. PMID 26123955.

External links

| Classification |

|---|